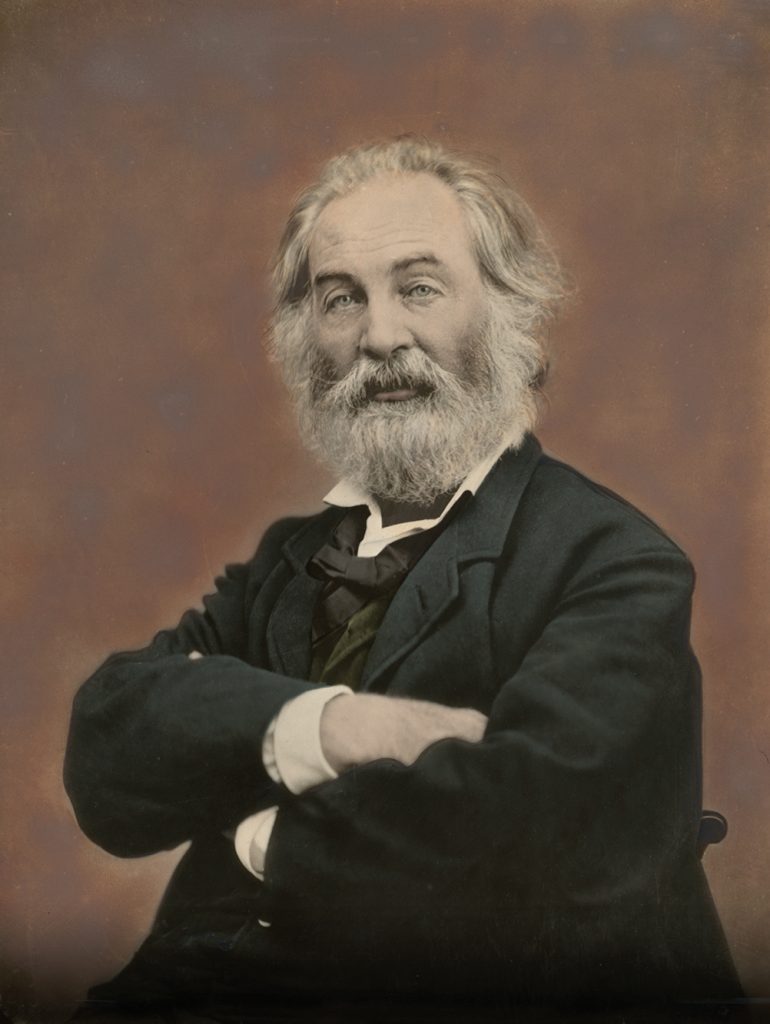

Walt Whitman’s Souvenir of Anguish

ECW welcomes guest author Tina Daniels.

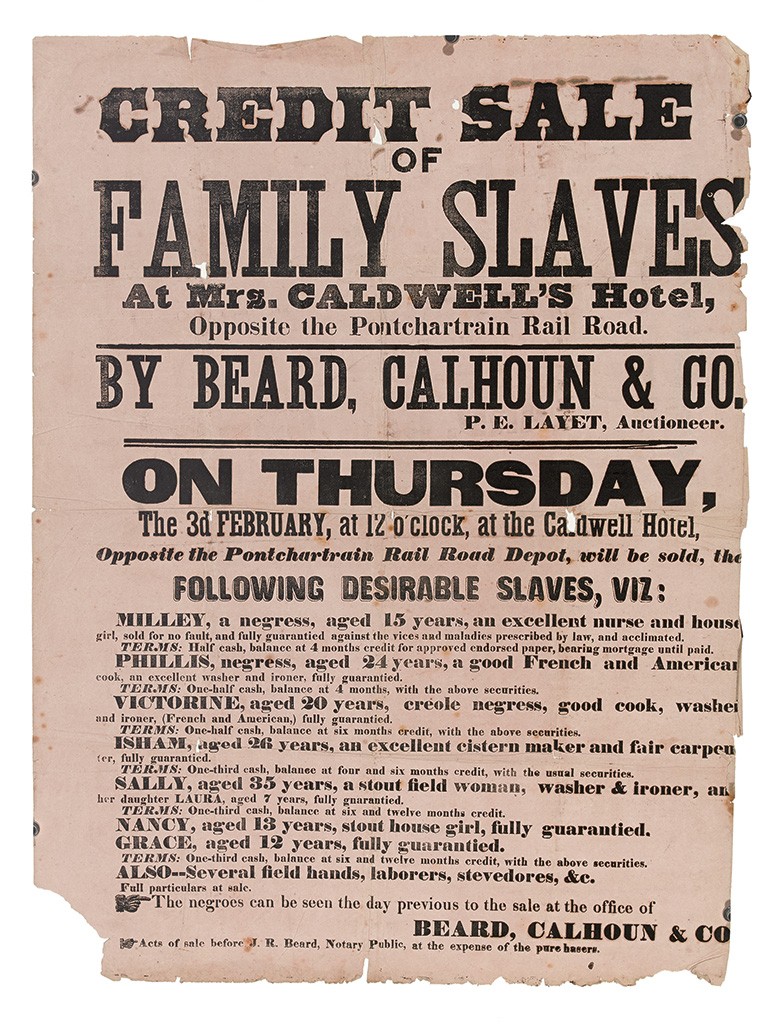

Walt Whitman, attending an 1848 slave auction in New Orleans, never imagined the value of a broadside, advertising a slave auction would be estimated at $6,000, never mind a mind-boggling price reached, in 2015, of $37,500.

The average annual income in 1850 was about $110.00. At least in Southern states, owning a slave was a signal that you possessed wealth and social standing. The average sale price for a slave in 1850 was $400.00 in the South and that was roughly equal to the purchase price for a home in that time.[1] No wonder families were split up; the people units alone were more valuable than the family, and very few people could afford a whole family.

Whitman himself had complicated political views about slavery. In 1846 when he was editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Whitman had castigated the anti-slavery activist as a ‘few . . . foolish red-hot fanatics,’ and warned that the ‘the dangerous and fanatical insanity of ‘Abolitionism [is] as impracticable as it is wild.’ He despised equally the abolitionist and the proslavery hotheads of the South whom he blamed—not without cause—for the fracture of the Union. In his poetry he tried to find a balance between the two.[2]

Nevertheless, Whitman was interested in Free Soil politics and in August 1848 served as a local delegate to the national convention in Buffalo, New York, where the Free Soil party was born. He edited a short-lived Free Soil newspaper, the Brooklyn Freeman. Whitman’s Free Soil politics is the main theory of why Van Anden, the owner of the Eagle, dismissed him in January 1848.

This was the job Whitman kept the longest: two years. But Whitman was a man who would not compromise his principles and was obstinate. If Van Anden asked him to tone down his editorials about the Free Soilers, Whitman would not budge.

However, by February, and within a quarter of an hour after meeting a Mr. McClure, a part-owner of the New Orleans Daily Crescent, Whitman was hired to be the editor, and his fifteen-year-old brother Jeff came along to be the office boy. The Crescent didn’t even exist yet, but started publishing in March 1848.

Though nothing else is known about the incident, Whitman used the 1848 New Orleans slave auction experience later in the poem “I Sing the Body Electric.” It was quite the shock for him to see people so dehumanized, often stripped mostly naked, males and females inappropriately touched and man-handled and put on an auction block. He would have heard the auctioneer describe young girls as “fancy,” the code for being sexually ready and active for their masters, a term and sight that so disturbed a nineteen-year-old Abraham Lincoln, when he heard it at a New Orleans auction with his friend Allen Gentry, Lincoln, “whose fists tightened till the knuckles were white,” said, “Allen, that’s a disgrace. If I ever get a lick at that thing I’ll hit it hard.”[3]

Likewise, Whitman was disturbed enough by what he saw at slave auctions while he worked at the New Orleans Daily Crescent in 1848 that he tore down a broadside similar, if not identical, to this broadside and kept it with him for decades on the wall of wherever he called home.[4]

Broadsides were the mass advertising and communication of the day; they were usually done in wooden block printing and led very ephemeral lives. No one in 1848 expected that broadside to be around and in an art auction in 2015, 167 years later. There were broadsides for everything and for every type of sale or announcement. They were meant to rally like-minded people to attend any type of function, like a slave auction or, if a slave was a runaway, to gather men to go hunt them. Broadsides announced steamboat and railroad schedules as well as local legal proceedings.

We do not know why Whitman kept this particular broadside. The slave auctions made a big impression on him, one that he didn’t want to forget. We can only make guesses now. He never wrote about the broadside, but we do know that he was conflicted about slavery. His poetry reflects that. We can only assume he was bothered by the splitting up of families or the emotions and heart-wrenching cries of slaves begging for people to buy their children, husband, wives, siblings.

This was not slavery as he understood it from his Long Island upbringing. His great-grandfather owned slaves, and it was legal in New York until 1828. Long Island had a much more Southern attitude towards slavery than the rest of the North and certainly than New England, to which it didn’t belong. Whitman was nine in 1828, and one of his closest companions was a freed slave named “Old Mose.” Whitman described him as “very genial, correct, manly, and acute, and a great friend of my childhood.”[5]

The unpleasant experience of the auction shows up in his poetry because he incorporates it in his poem “I Sing the Body Electric” in his first edition of Leaves of Grass (1850):

A man’s body at auction,

(For before the war I often go to the slave-mart and watch the sale,)

I help the auctioneer, the sloven does not half know his business.[6]

Whitman also wrote a poem in 1850, two years after the slave auction, called “Blood-Money,” and that is his first public expression of sympathy for fugitive slaves. Whitman had been in favor of the Fugitive Slave Law, but after the auction and seeing the different posters for auctioning off live human beings, he starts to see a different dimension to the idea of “lost property.” He starts seeing them as real human beings. This poem was reprinted in the New York Evening Post, April 30, 1850, and in Specimen Days (1882).[7]

Asking Christ to identify with the slave, he wrote:

The meanest spit in thy face—they smite thee with their palms;

Bruised, bloody and pinioned is thy body,

More sorrowful than death is thy soul.

Witness of Anguish—Brother of Slaves,

Not with thy price closed the price of thine image;

And still Iscariot plies his trade.

– Walter Whitman[8]

Whitman was a complex character with many facets. He was not an abolitionist as witnessed by his Brooklyn Daily Times editorial in 1858:

“Who believes that Whites and Blacks can ever amalgamate in America? Or who wishes it to happen? Nature has set an impassable seal against it. Besides, is not America for the Whites? And is it not better so?”[9]

Whatever he experienced at the slave auctions in New Orleans made a deep enough impression on him that he kept that broadside for decades and took it from place to place wherever he lived.

Tina Daniels is cohost of Civil War Talk Presents for the CivilWarTalk.com website and Forum Host. She is studying at Oxford University for diploma in Local History. Due to strange birth order and longevity, her grandfather and father took care of Civil War vets in their own home, and she knew her grandfather very well!

Endnotes:

[1] Samuel H. Williamson and Louis P. Cain, “Measuring Slavery in 2020 Dollars,” Measuring Worth, https://www.measuringworth.com/slavery.php.

[2] Roy Morris Jr., The Better Angel: Walt Whitman in the Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 81.

[3] Phillip Shaw Paludan, “Lincoln and Negro Slavery: I Haven’t Got Time for the Pain,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 27, no. 2 (Summer 2006): n.p. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0027.203/–lincoln-and-negro-slavery-i-havent-got-time-for-the-pain?rgn=main;view=fulltext

[4] Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, “Walt Whitman,” The Walt Whitman Archive, https://whitmanarchive.org/whitmans-life/biography.

[5] Morris, The Better Angel, 80.

[6] Walt Whitman, “I Sing the Body Electric,” Leaves of Grass, The Walt Whitman Archive, https://whitmanarchive.org/item/ppp.00707_00736.

[7] “Blood-Money” notes, The Walt Whitman Archive, https://whitmanarchive.org/item/per.00089.

[8] Walt Whitman, “Blood-Money,” The Walt Whitman Archive, https://whitmanarchive.org/item/per.00089.

[9] Walt Whitman, I Sit and Look Out: Editorials from the Brooklyn Daily Times (New York: AMS Pres, 1966), 90.

If memory serves, Whitman also visited the mines, factories, mills and workhouses in the north, witnessing the horrific conditions there. He was curious about everything in America, to our benefit.

It’s so interesting to read Whitman declaring “segregation forever”. Slavery was the regime that kept this idea believable to a large number of Americans, and the Civil War and Reconstruction Amendments were the causes that made it eventually untenable.