“To Reopen that Great Highway”: John McClernand, Vicksburg and the Filibustering Tradition

ECW welcomes back guest author Devan Sommerville.

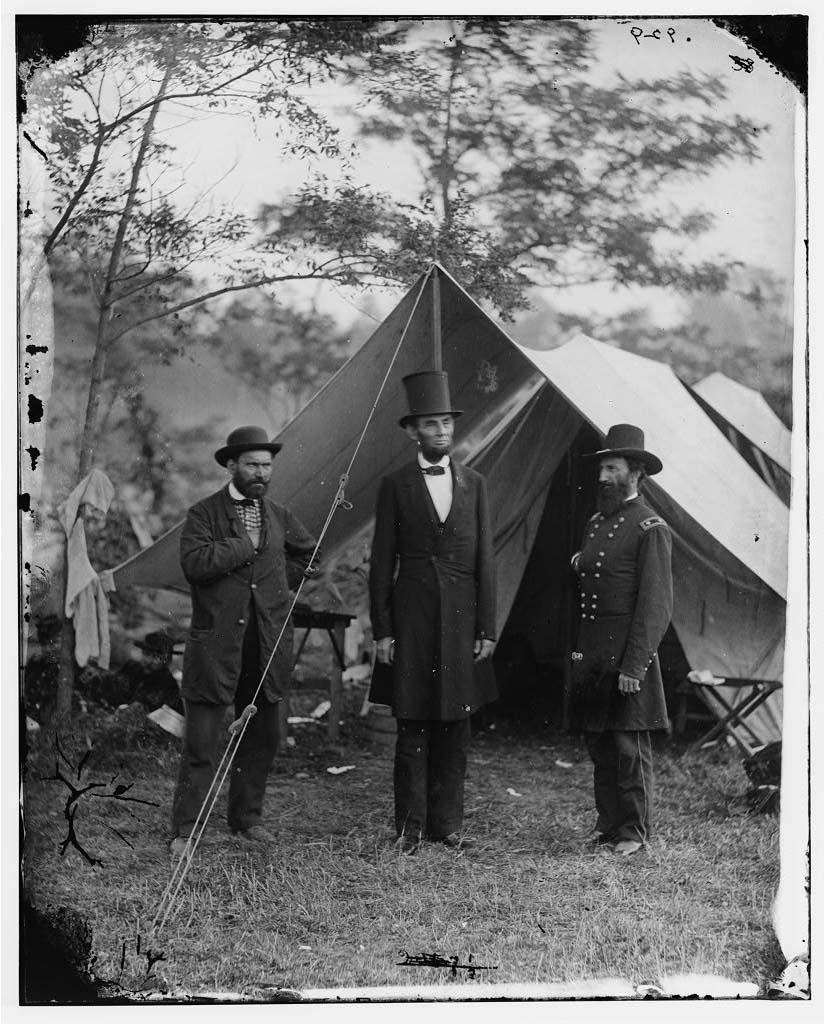

President Abraham Lincoln visited the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac in October 1862. During this time, he was captured by photographer Alexander Gardner in a series of photographs.

In one famous image, Lincoln towers over two men flanking him. One, civilian detective Allan Pinkerton, was George McClellan’s intelligence chief and Lincoln’s escort during his inauguration journey.

The other figure, Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand, had recently arrived from the West. A long-time acquaintance of Lincoln, the president invited him to accompany the trip up the Potomac. It was an irresistible opportunity. McClernand had an exciting proposal: with the president’s blessing, he would raise an army and capture the Confederacy’s crown jewel—Vicksburg.

Although a defining event of the American Civil War, the Vicksburg Campaign emerged unconventionally. Control of the Mississippi River was crucial in Union strategy from the war’s outset. Lincoln perceived Vicksburg as the key to Confederate control of the river; a Union victory would be elusive “until that key is in our pocket.”[1] As long as Vicksburg remained in Confederate control, cotton and supplies from as far as Texas could travel down the unimpeded Red River to Vicksburg, from where they would be transported across the South. Yet amid abortive attempts and setbacks, meaningful efforts to capture the city had yet to begin.

For McClernand, a Vicksburg expedition was a political and personal opportunity. Elevated as an influential pro-war Democrat from Southern Illinois, McClernand’s reputation was at a high ebb, shaped by personal bravery and credible performances at Belmont and Shiloh – ably publicized through the Northern press. He also resented the West Point officer corps and chafed under its authority.[2]

His plan reflected his preferred approach: direct offensive action rather than strategy and maneuvers.[3] The proposed Vicksburg expedition drew on a populist military tradition: filibustering. Derived from the Spanish for “lawless plunderer,” it described extralegal, private military ventures launched by Americans in Latin America. Filibustering peaked in the 1850s as a Southern effort to expand plantation slavery.[4]

The free-enterprising military culture of the antebellum frontier was familiar to a Jacksonian Democrat like McClernand. But he turned filibustering’s character on its head: instead of expanding slavery, he aimed to strike a decisive blow to the rebellion.

Like his Southern predecessors, McClernand’s filibuster was regionally motivated. Western farmers faced hardship from the Mississippi’s closure, undermining support for the war. Indiana Governor Oliver Morton described the issue of free navigation on the Mississippi as having “the most potent appeal” for Northwestern voters, “requiring only to be stated to be at once understood and accepted.”[5]

McClernand echoed that sentiment. Re-opening the Mississippi River to northwestern commerce “would be hailed by a suffering people with the loudest exclamations of gratitude.”[6] But the window for action was closing. He warned Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that without action to “reopen that great highway,” Northwesterners would be drawn to those that “favor the recognition of the independence of the so-called Confederate States, with the view to eventual arrangements, either by treaty or union.”[7]

McClernand reinforced this through political connections. He spurred a petition to Lincoln from Northern governors praising his military accomplishments and urging “his assignment to an independent command…in the Mississippi Valley.”[8] His strongest leverage was his personal relationship with Lincoln. Though partisan adversaries, they shared cordial ties since their time in the Illinois state legislature. Lincoln recognized McClernand’s value in maintaining popular support for the war among Western Democrats.[9] Lincoln also described him as “brave and capable, but too desirous of being independent of everybody else.”[10]

This entrepreneurial spirit was soon apparent. On October 21, 1862, he received orders to organize regiments in Illinois, Indiana and Iowa for “an expedition under General McClernand’s command against Vicksburg and to clear the Mississippi River.”[11] Based in Illinois, McClernand acted quickly, securing support from the respective governors.[12] He was assisted by a note from Lincoln appended to his orders, expressing the President’s “deep interest in the success of the expedition, and desire it be pushed forward with all possible despatch.”[13]

McClernand described the expedition in filibustering language. In correspondence with Stanton, he called it an “enterprise” and said he was “to do all in my power to promote it.”[14] He treated the mobilization personally, telling one counterpart that he was ordered to “enlist an army at Springfield, Illinois, and command it at the siege of Vicksburg,” and understood from Stanton that his “personal influence” was to be relied on.[15] He also attended to details more characteristic of a private military venture than the operational responsibilities of a senior commander. His personal correspondence with the secretary of war specified the size of tents, distribution of small arms at the company level, and artillery calibers.[16]

He also sought personal and political loyalty. To stiffen the expeditionary force, McClernand requested thirteen veteran regiments, mostly from his division in the Army of the Tennessee. He also requested preferred officers to serve as brigade and division commanders, rising stars without formal military education and committed War Democrats like himself.[17]

McClernand reached across partisan lines to other soldiers that shared his entrepreneurial approach. He successfully encouraged Frank P. Blair, the Missouri Republican congressman and general who was instrumental in securing that state for the Union, to petition Lincoln to include Blair and his newly raised brigade in McClernand’s expedition.[18]

A seasoned politician, he used the press to shape public perception and promote his venture. Almost immediately upon his arrival in Springfield, word spread that he was leading an expedition against Vicksburg.[19] McClernand cultivated fawning coverage. “Gen. McClernand is an energetic man. He personally supervises everything himself. He is indefatigable, watchful, and brave,” recounted the Chicago Daily Tribune; “there are no ‘ifs,’ or ‘ands,’ or ‘buts,’ with him in the prosecution of this war.”[20]

The Illinois State Journal informed its readers that “McClernand is one of the fighting Generals, and just the man for driving the rebels from their strongholds at Vicksburg.”[21] A lithograph of the general was also available, the paper re-assuring readers they would be “gratified to know that such a likeness is in existence.”[22]

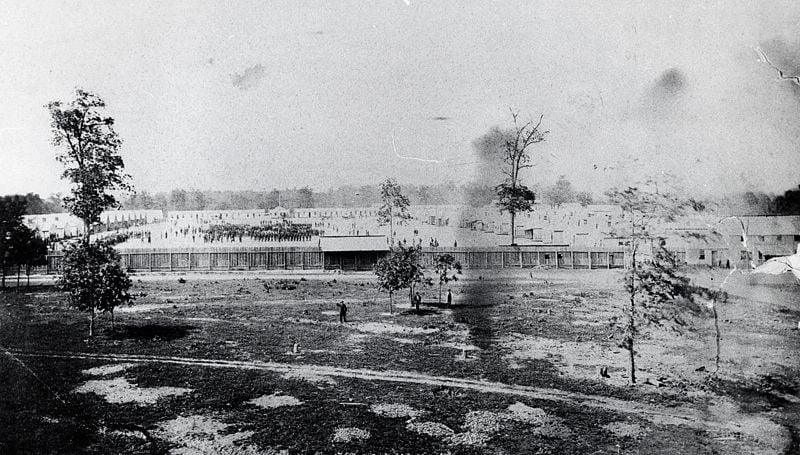

Ultimately, McClernand claimed that through his efforts, 49 infantry regiments and two batteries of artillery – 40,000 men – were forwarded for “the Mississippi expedition.”[23] Although these regiments were overwhelmingly recruited prior to McClernand’s arrival, he and his staff exercised considerable energy to ready the new levies in less than two months.[24] The men organized by McClernand were imbued with his filibustering spirit. William T. Sherman observed that “the new troops come full of the idea of a more vigorous prosecution of the war, meaning destruction and plunder.”[25]

McClernand the filibusterer had raised his expeditionary force. Unbeknownst to him, others were moving to assert control over both the manpower and the mission. Henry W. Halleck, general-in-chief of the Federal Army, maintained no confidence in McClernand’s capability for independent command. Finding sufficient flexibility in the War Department’s orders, he worked to harness McClernand’s organizational energy while delaying his presence at the front to lead the campaign. Through Halleck’s initiative, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant found himself tasked to lead the campaign that would enshrine his legendary reputation and position him as the pre-eminent General of the Union Army.

Devan Sommerville is a consultant lobbyist based in his native Canada, living in Toronto, Ontario with his wife and young son. A lifelong student of the American Civil War and American Antebellum History, he holds an Honours Bachelor of Arts in History and a Master’s in Public Policy from the University of Toronto.

Endnotes:

[1] Abraham Lincoln in David Dixon Porter. Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (New York: D. Appleton, 1885), 96.

[2] Richard L. Kiper. Major General John Alexander McClernand: Politician in Uniform (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999), 135.

[3] Kiper, 135.

[4] For an examination of filibustering and its link to pro-slavery expansionism, see Walter Johnson. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2013).

[5] Oliver Morton to Abraham Lincoln. ALP, October 27, 1862.

[6] John McClernand to Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln Papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833-1916 – September 28, 1862.

[7] The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 334.

[8] Richard Yates to Abraham Lincoln. ALP, September 26, 1862.

[9] Josiah Grinnell. Men and events of forty years: autobiographical reminiscences of an active career from 1850 to 1890. (Boston: D. Lothrop Company, 1891), 174.

[10] Salmon P. Chase. Salmon P. Chase Papers: Diaries, -1870; 1862, July 21-Oct. 12. – October 12, 1862, 1862. September 27, 1862.

[11] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 282.

[12] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 332.

[13] Roy Basler, ed. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press), 5:469.

[14] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 333.

[15] Porter, 123; OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 308.

[16] John McClernand to Edwin Stanton. Edwin McMasters Stanton Papers: Correspondence, -1870; 1862, Aug. 29-Dec. 19. – October 10, 1862.

[17] John McClernand to Edwin Stanton. EMSP, October 10, 1862.

[18] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 351; Francis Preston Blair to Abraham Lincoln. ALP, November 1862.

[19] Chicago Daily Tribune. October 28, 1862, 1.

[20] Ibid. December 27, 1862, 1.

[21] Illinois State Journal. October 27, 1862, 3.

[22] Ibid. November 25, 1862, 3.

[23] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 401.

[24] Kiper, 153.

[25] OR, Series 1, Vol. 17, Part 2, 351.

Concise and balanced report.

After Halleck’s 100,000-man army occupied Corinth in May 1862 and “drove the few surviving rebels” south to Guntown Mississippi in June, Major General Halleck viewed the situation in the Western Theatre as “under control” and turned his attention to rebuilding railroads for Federal use; in particular, the Memphis & Charleston Railroad was ordered restored from Memphis (where Grant established his HQ) to Chattanooga (where Buell was to take control after rebuilding the railroad during the march east from Corinth.) Halleck departed for Washington D.C. in July to become General-in-Chief of the Armies. And Federal focus in the West devolved into defensive operations, at the exact time Rebel operations under Bragg and his reconstituted army went on the offensive, tearing up tracks and derailing trains as soon as key stretches of track were rebuilt. The daily grind to rebuild railroad tracks and infrastructure during the day, only to see that work destroyed by fire overnight, became a thankless job that was obvious in its inability to win the war. Major General McClernand took a leave of absence from rebuilding railroads and journeyed east to consult with President Lincoln about “a better way forward” …and Devan Sommerville admirably picks up the story from there.