Ethics and Issues: Introduction

Earlier this summer, a friend of mine wrote a Facebook post that caught my eye: “An ethical conflict studies statement.”

The friend, John R. Heckman, the Tattooed Historian, is working on his doctoral degree in Canada. His multidisciplinary work touches on a variety of subject areas, including history, digital humanities, conflict studies, and ethics. Sitting at that intersection, he felt compelled to take a sort of “time out” to explore and explain—to himself as well as his readers—what it means to study conflict in an ethical way.

His statement resonated with me—strongly. I have been grappling of late with a few ethics-related issues, as well, and suddenly here was someone giving voice to concerns related to the ones I’d been rolling over in my head.

Specifically, as I wrote last fall when my book A Tempest of Iron and Lead: Spotsylvania Court House came out, I found it incredibly challenging to write about violence for that book. The battle of Spotsylvania had violence enough for any thousand lifetimes, compressed into thirteen days. I wanted to accurately capture the horror of the men so that I could do justice (even if in a small way) to their experience. But conversely, I did not want to be titillating, sensationalistic, or gratuitous. I found it hard to find the right line to walk even though I clearly knew which side of the line I wanted nothing to do with. (You can read my full essay on the violence in Tempest here.)

Of course, that’s not the only time I’ve wrestled with a matter of conscience in the course of my work. I recall an incident from nearly a decade ago while I was working at the Stonewall Jackson Death Site (then called the Jackson Shrine). A group of visitors came in and began talking about “States Rights,” and I gently pushed back with questions about slavery.

I later wrote a blog post about the incident. A colleague responded by taking me to task for my answer. He claimed my job, as an NPS representative, was to respect “all opinions and viewpoints.” It was? I thought my job was to educate, not smile and nod. What was my responsibility in that moment? (You can read the story here if you’d like and decide for yourself.)

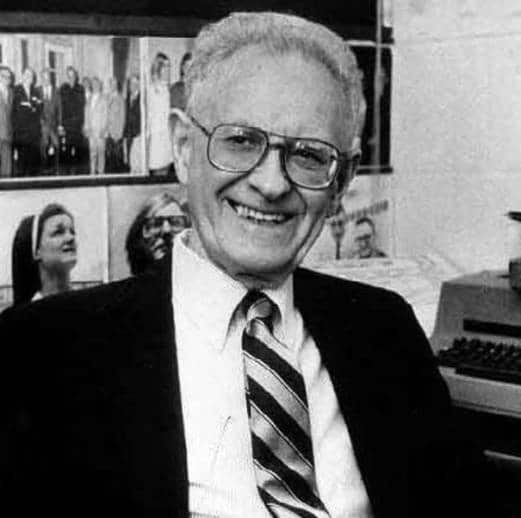

I teach in a School of Communication deeply grounded in ethics. Our founder, Russell J. Jandoli, was one of those old school newspapermen who bled black ink (and, himself, a one-time student of Douglas Southall Freeman at Columbia). In Russ’s worldview, personal and professional integrity served as the core of everything a reporter did, because if he or she didn’t have integrity, no one would trust him: no sources, no editors, no readers. You cannot serve your public if your public doesn’t trust you. (Today’s media environment proves that point, doesn’t it?) Under Russ’s founding vision, our journalism program developed a national reputation for our twin pillars of strong writing skills and a commitment to ethics—an approach we adhere to to this day.

Coupled with that approach is St. Bonaventure University’s Franciscan mission. As my colleague Pat Vecchio recently articulated it:

St. Bonaventure University’s Franciscan values are:

- The fundamental goodness and value of the natural world.

- The fundamental dignity and worth of all human beings.

- The importance of community.

- The importance of being open to the transcendent.

- Simplicity and humility as a way of life.

- Joy as a natural response to life.

Those bullet points are baked into my everyday life, and I’ve spent a lot of time thinking specifically about how those values inform my work as a writer and communicator. When ethical quandaries arise, I look to those values for guidance because they are the things I believe the most.

So how do ethics play into what we do as historians?

That’s the question I posed to my colleagues at ECW. What follows over the next two weeks will be their responses. My hope is that you’ll get a sense of the wide array of ethical challenges we face as we practice the craft of history.

Also as part of our series, you’ll hear from the Tattooed Historian as well as our mutual friend Prof. Jonathan Noyalas at Shenandoah University’s McCormick Civil War Institute. John and Jonathan and I recorded a three-way conversation for this week’s Emerging Civil War Podcast. In the meantime, I also want to invite you to read John’s “Commitment to Ethical Conflict Studies.” It’s the piece that triggered this whole series, so perhaps it’s a good place for all of us to start.

I’m looking forward to seeing where this discussion goes in the series. With the particular war being discussed 160+ years in the rearview, with battles being only part of the story, there is a great responsibility in interpreting/analyzing the stories about people no longer around to explain themselves. There are so many layers and nuances to explore. I am eager to consider your three perspectives!

Chris, an excellent introduction to an important topic. I look forward to reading the series.

There is an old saying from someone, somewhere, that “the first casualty of war is the truth.” One of the most important responsibilities of those who study and then report on war – any war – is to put the lie to that saying.

The experience of fightng in the Civil War is “incommunicable” The violence, the noise, the smell. When I am standing on a Civil War battlefield, I have enough insight to realize that the manicured fields and silent cannon are not what was experienced or processed by the participants. I am probably replaying a war movie. Even livng veterans of modern conflicts had a different experience than the soldiers of 160 years ago.

When I teach the Great Depression, we read accounts of people who lived through it, and that gives some idea to students who our inquiring enough to engage with the text. But to really understand it, I should have the students each flip a coin and everyone who got “heads” goes home as normal, and everyone who got “tails” gets nothing to eat and doesn’t go home, but gets a newspaper for warmth and has to sleep outside on the school grounds. Then we flip the coin again, the next day, and the next and the next. Then maybe they would have an idea. But that’s not going to happen

Anyway, this is an interesting series.