Ethical Issues in Studying the Civil War – The Risk of “Self-Censorship”

Some twenty years ago my interest in the Civil War was challenged in unexpected fashion, and in a manner that still resonates with me today. That experience exposed a certain type of “risk” that accompanies being a Civil War historian (even as an amateur), one that I suspect is shared by others whose passion focuses on the study of “America’s defining event.” And, as discussed below, this risk implicates a potential ethical issue—professional “self-censorship.”

Some twenty years ago my interest in the Civil War was challenged in unexpected fashion, and in a manner that still resonates with me today. That experience exposed a certain type of “risk” that accompanies being a Civil War historian (even as an amateur), one that I suspect is shared by others whose passion focuses on the study of “America’s defining event.” And, as discussed below, this risk implicates a potential ethical issue—professional “self-censorship.”

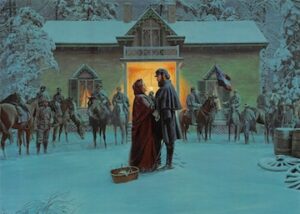

The setting for the referenced challenge was my law office. The speaker was a junior attorney with whom I worked, and so often visited my office. Not surprisingly, my office décor reflected my loves and interests. In addition to the usual family photographs, framed diplomas and bar admission documents, my office was marked by Civil War memorabilia. I had prints of Grant and Lee at Appomattox, a Mort Kunstler of Stonewall Jackson (“Until We Meet Again”), a large framed antique woodcut of a U.S. assault on the works at Vicksburg, another print of Stonewall, and small busts of Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. My bookshelves at the time also probably included Civil War books among the law tomes. The room screamed the Civil War.

The associate attorney seemed to have an issue with that. She questioned me on my clearly deep interest in the conflict. While I cannot recall the words used, I gained the sense that the associate—an African American—was suspicious of my interest. While I was not explicitly being accused of sympathizing with the Confederate cause, my radar went up. My colleague was seeking not just an explanation, but a justification. I explained that my interest in the conflict was partly due to my love of American history generally (my undergraduate degree is in History), and that the War was fascinating because it was fought here. But I went further, explaining—as any reasonably competent historian would—how the past affects the present. And, I continued, as we both were Labor & Employment Law attorneys, we each especially should be interested in the present-day impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction Era because so much of our current employment and civil rights law arose from that part of our past.

While I doubt that I was as verbally articulate back then as my present writing suggests, I think that my explanation satisfied the associate. Yet the incident has stayed with me, because it alerted me to the risk of being misunderstood. I know that some people think that showing too great an interest in what they see as the moldy past is odd. But it seems that some may think that interest in the Civil War automatically reflects an admiration for the Confederacy. Am I reading too much into one long-ago encounter? I think not. Prominent historian and author Dr. Gary Gallagher has perceived the same risk of public misperception of what motivates those who study the Civil War, especially if that study leads to what some might see as “wrong” conclusions. In his introduction to The Confederate War, Dr. Gallagher wrote:

“Any historian who argues that the Confederate people demonstrated robust devotion to their slave-based republic, possessed feelings of national community, and sacrificed more than any other segment of white society in United States history runs the risk of being labeled a neo-Confederate.”[1]

In other words, simply applying normal historical analysis to the study of the Civil War can lead to being called a Confederate apologist, white supremacist, and/or a racist. Similarly, expressing admiration for any figure associated with the Confederacy can likewise result in the same charge, even if that admiration is focused on some talent or trait (e.g., Robert E. Lee’s audacity on the battlefield) separate and wholly apart from the cause for which the Confederacy was fighting.[2]

A potential result of fearing being labelled with one of the foregoing derogatory terms is professional self-censorship. A historian of the Civil War might be tempted to “trim his sails,” so to speak, and either tailor the conclusions of his (or her) research to avoid appearing sympathetic to the Confederate cause, or avoid tackling controversial topics altogether. Either approach would be inconsistent with the role of the historian to go where the historical facts lead and thus could be deemed professionally unethical. Indeed, the American Historical Association recognizes this risk: “Professional integrity in the practice of history requires awareness of one’s own biases and a readiness to follow sound method and analysis wherever they may lead.”[3]

I have confronted this risk, in different forms, at various stages of my career as an amateur historian. For example, being a former attorney, I once decided to write an article analyzing the legality of secession. I realized that to be objective, I would need to acknowledge legitimate arguments from the history of the Constitution that would tend to support secession. So be it, I thought. Yet I felt compelled to include a sort of disclaimer up front. I wrote that “… the question examined here is whether, as a matter of law, the U.S. Constitution as it existed in 1860 authorized secession. The issue is not whether the Southern states exercised any such purported legal right for a morally worthy purpose. In this regard and by way of analogy, we may concede that a person has a perfectly legal right to end a marital relationship, while simultaneously abhorring the particular circumstances (e.g., unfaithfulness towards a loving spouse) that sparked the person’s exercise of that right of divorce.”[4] That language provided “cover” for a discussion of any pro-secession points. However, the fact that I felt compelled to seek such cover reflected a concern that presenting an objective legal analysis might inflame some readers who would then misjudge my own personal belief as to the supposed “rightness” of the position taken by the seceded states.

Another time an editor working with me on a journal article cautioned me not to write that I had visited a historic cemetery to “pay my respects” to one of the interred, because he was a CSA officer. The editor was concerned that using that language, especially in an introductory section, might conceivably turn off some readers. I whole-heartedly agreed with the editor, deeming it a “good catch” of language that was in reality simply a turn of phrase. That incident reminded me of the need to be “careful” in how one writes about the Civil War, out of concern over how one’s words might be misperceived.

Further, I once was (mildly) concerned about how to describe an award that my Round Table earned. The award, presented by a local group dedicated to historic preservation efforts, was in the category of “Heritage Education.” Our Round Table primarily teaches Civil War history through our excellent speaker series, which covers a wide variety of aspects of the War from multiple perspectives. But, for a fleeting moment, I worried that someone might flash on the word “heritage” and think of the “Heritage, not Hate” bumper sticker slogan often employed by those who defend the display of the Confederate battle flag on public buildings, and draw an unwarranted conclusion about our non-partisan history education group.[5] I quickly discounted such fear, but again, the thought had given me pause.

Finally, another concern arose when writing a blog entry for Emerging Civil War. The subject of the post was the “insurrectionist disqualification” clause of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution and its applicability to then former-President Donald J. Trump.[6] I realized that in presenting my lawyer’s analysis of a recent Supreme Court case on the issue, I was wading into a very charged area. While not implicating any supposed pro-Confederate issues, you can be assured that I was aware that my writing might spark a bitter political debate. Again, I thought, so be it.

Having said “so be it” in various scenarios, however, is not to ignore the pressure that may be felt when tackling certain types of historical issues surrounding the Civil War. The historian who recognizes the possibility of being tarred with unflattering epithets due to the subject he is addressing, and/or the conclusions drawn, also must recognize the risk that he may be tempted somehow to subtly alter his work. Perhaps the writer will change what he would prefer to express in writing, or alter his emphasis, or even (perhaps subconsciously) alter his conclusions, all in an attempt to avoid being misperceived. Perhaps the writer will feel self-pressure to avoid all praise of a particular historical character, on any topic whatsoever, because the subject was an enslaver, or simply because he supported the Confederacy. That could lead to readers missing out on elements of the subject’s character that help bring him to life or explain his motivations. Or maybe the writer will shy away from tackling certain War-related subjects, worrying that they might be too controversial. That could deprive the public of the opportunity to learn about an important subject.

All of this presents ethical issues for those of us who have a passion for studying the Civil War, especially in these contentious times. The purpose of a historian is to research the facts, analyze such as objectively as possible, and offer reasonable conclusions, based on the available evidence. The temptation to self-censor to avoid potentially uncomfortable public backlash represents pressure that the ethical historian must resist.

————

[1] Gary W. Gallagher, The Confederate War: How Popular Will, Nationalism, and Military Strategy Could Not Stave Off Defeat (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1997), p. 13 (emphasis supplied).

“Neo-Confederacy” refers to “groups and individuals who portray the Confederate States of America and its actions during the American Civil War in a positive light.” “Neo-Confederates,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo-Confederates. The phrase has been defined as a “branch of American white nationalism typified by its predilection for symbols of the Confederate States of America.” The Southern Poverty Law Center, https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/neo-confederate/.

[2] Ulysses S. Grant was able to draw such a distinction, writing about Lee that “I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought…”. Ulysses S. Grant, John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo, Eds., The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2017), pp. 721-722. Grant ascribed the cause of the War to slavery. Id. 756.

[3] “Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct (updated 2023),” American Historical Association, https://www.historians.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Statement-on-Standards-of-Prof-Conduct-Jan-2023.pdf(emphasis in original).

[4] “Secession Revisited: A New Legal Analysis,” North & South, Series II, Vol. 4, No. 5 (December 2024), p. 83 (emphasis in original).

[5] ‘“Heritage, not Hate” is the familiar bumper sticker defense of the Confederate flag. It has evoked equally pithy responses, such as “Your Heritage is Hate” and “Heritage of Hate.”’ John Coski, “Myths & Misunderstandings, The Confederate Flag,” American Civil War Museum, January 9, 2018, https://acwm.org/blog/myths-misunderstandings-confederate-flag/.

[6] Kevin Donovan, “Making America’s Civil War Great Again: Donald J. Trump Proves That the Civil War Still Matters,” Emerging Civil War, April 19, 2024, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2024/04/19/making-americas-civil-war-great-again-donald-j-trump-proves-that-the-civil-war-still-matters/.

Thank you, excellent explanation.

As long as your fair, honest, and transparent – you should ignore those who are slow to listen and quick to judge.

I really enjoyed this piece, Kevin. I run into a similar sort of thing. As many ECW readers know, I am an unapologetic Stonewall Jackson fanboy. The reasons for that relate entirely to the connection I forged with Jackson’s story back when my daughter was little. She fell in love with Jackson, and we spent years exploring his story and visiting sites together, and that’s ultimately what led me to Civil War history. People today sometimes assume that I must love the Confederacy because I’m a Jackson devotee, but that’s simply not the case. (As many ECW readers also know, I am vehemently anti-Lost Cause!) My connection with Jackson is deeply rooted in personal rather than historical reasons–but that’s easily misunderstood by people who don’t bother to ask.

Chris, thank you. And I agree with your sentiments.

Excellent work, Kevin!

Thank you sir.

As usual, excellent analysis and scholarship, Mr. Donovan!

Thank you my musician friend.

Perhaps in the same vein, after Floyd my wife was all of the sudden objected to the flying the American flag at our house on Memorial Day, July 4th (Betsy Ross flag), and Veterans Day. She had heard or read where someone called the American flag racist and was concern a black person passing by would take offense. I my response was that neither of us were or had been racist and I was not going to limit what I liked to do solely to avoid a confrontation (which has never happened). I have no intention of allowing another group define what the American flag means to me.

Kevin, think back to that experience which you related with your young colleague. Surely, the professional relationship was one of mutual respect. After your explanation of your historical interests, as evidenced by your office decor, were you able to perceive a palpable change in the colleague’s professional relationship toward you? In other words, was your self censorship successful in maintaining your professional relationship without any change?

Bill, yes our professional relationship went on as before, as the attorney understood my perspective and, I think, saw the Civil War (and those of us deeply engaged in its study) in a new light. Thank you for reading.

Anyone who has ever posted any comments in a Civil War forum should read this.

Kevin, I appreciate your thoughtful essay. I practiced law for 45 + years in a large firm with offices on both sides of the Mason Dixon line. Many lawyers were accomplished Civil War students and authors. Some were avid collectors of images and artifacts, read Blue&Gray or Military Images, etc., frequent trekkers to battlefields, etc. I never sensed any thought that interest in the Civil War, or in collecting photo or artifacts, was something that required explanation or justification. I enjoy your many contributions to ECW. Thanks

You might want to recognize that your junior African-American colleague took a very great personal risk in asking you about your chosen decor. And also that she listened to your explanation. I hope you thanked her for asking you those questions. She could have kept silent and drawn reasonable conclusions about your views on the conflict based on the decor. Art that elevates Jackson and Lee to god-like status is at the heart of Lost Cause mythology, and the Kunstler print really embodies many of the sentimental tropes of the Lost Cause narrative. It doesn’t sound like this was an effort to censor you, but to understand where a colleague was coming from. Consider it a sign of her respect for you that she asked these questions.