Confederate Leadership at Sharpsburg: Center Line, 9:30 – 10:30 a.m. Part 3

Sunken Road (Bloody Lane)

General R. E. Lee rode over to the center of his line as the Confederates took up secondary positions near the West Woods, Wednesday morning, Sept. 17, 1862. Division commander Brig. Gen. D. H. Hill and his brigade and some regimental commanders met Lee. Hill had deployed his men in a sunken farm lane that zig-zagged through the center of their line. According to Col. John B. Gordon, 6th Alabama, Lee told them to be prepared for a “determined assault.” Gordon, and probably Hill, reassured their commander: “These men are going to stay here General till the sun goes down or victory is won.”[1]

Let’s stop here for a minute. This was an important, but simple conversation. The commanding general collaborated with his division, brigade, and regimental officers. Hill and his officers understood Lee’s intent: hold the line. Lee, in turn, trusted his men would hold until he could get them support or hold until the last man. Just the presence of the general also raised the elan of the officers and enlisted.

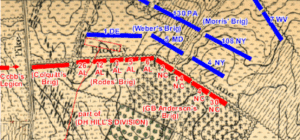

Lee was asking a lot because Hill didn’t have enough soldiers. He had two full brigades under brigadier generals Robert Rodes and George B. Anderson. The remnants of Col. Alfred Colquitt’s and Col. D. K. McRae brigades returned from fighting in the Cornfield and extended the line left. Survivors of Col. Thomas Cobb’s Legion got separated from its division and now anchored Hill’s far left.[2] The troops hailed from Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia. All toll: 2,700 Southern infantry waited with about seventy-six guns supporting them.[3]

The Confederates deployed in two thin lines. Some hunkered down in the sunken farm lane; others lay behind the first line on the rise above the road. The lane was on the reverse slope of a gently rising plateau.[4] It was a strong defensive position in some respects, and it hid the fact that Hill’s small force lay exposed, especially on the right.

“Here they come,” echoed down the ranks as the first Yankee division appeared around 9:00-9:30 a.m. Hill’s boys caught a break with the initial Union waves. The opposing division sent one brigade at a time, rather than two in line of battle (side-by-side).[5] The goal was to break the Confederate line using the tactical weight of the brigades in column (stacked up). Compounding the difficulty, some bluecoats had almost a mile to traverse through the shot and shell.[6]

Colonel Gordon felt some pity for his enemy and hated to spoil their well-dressed battle lines. It was such a scene of “’martial beauty’. But there was nothing else to do. Mars is not an aesthetic god; and he was directing every part of this game in which giants were the contestants.”[7] The Confederates sent a hailstorm into their foes just rods away. The first Union line crumbled. Those that survived receded back into the cornfield. Supporting troops came up, but instead of charging through their comrades, the reinforcements fired on the first line from the rear.[8]

Once the initial Union lines got straightened out, their men began blazing away at the Confederates. The blue waves ebbed and flowed against the Alabama troops. Casualties mounted on both sides. A mortally wounded Alabama father lay over his dead son. Colonel Gordon wrote,

“…though wounded and bleeding profusely in four places, [he] continued cheering his men, though oft entreated to leave the field. Seeing his men all dead and dying, till one could have walked the length of six companies on their bodies, his heart grew sick at the terrible havoc of death around him.”[9]

A fifth bullet slammed into Gordon. He finally crawled to the rear with five wounds and lived to tell about it. The Alabama boys remained at least for a little while longer.

Over on the Confederate right-center, G. B. Anderson’s North Carolina brigade defended against the infamous Irish Brigade. Some North Carolinians ran out of the sunken road and blasted the oncoming Irishmen. The New York and Massachusetts boys wavered, then regrouped, and halted a few more yards. “Fire!” echoed down the ranks.[10]

Lieutenant John C. Gorman of the 2nd North Carolina recalled the fighting:

“Our skirmishers began to fire on the advancing line, and we returned to ours. Slowly they approach up the hill, and slowly our skirmishers retire before theirs, firing as they come. Our skirmishers are ordered to come into the line. Here they are, right before us, scarce 50 yards off, but as if with one feeling, our whole line pour a deadly volley into their ranks – they drop, reel; stagger, and back their first line go beyond the crest of the hill. Our men reload, and await [sic] for them to again approach, while the first column of the enemy meet the second, rally and move forward again. They meet with the same reception, and back again they go, to come back when met by their third line. Here they all come. You can see their mounted riders cheering them on, and with a sickly “huzza!” they all again approach us at a charge, but another volley sends their whole line reeling back.”[11]

For all their effort, the Confederate line couldn’t take much more, and more Union brigades were moving up. It was around 10:30 a.m. The North Carolina and Alabama boys needed reinforcements.

[1] John B. Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War, 84. Map in this blog taken from https://antietam.aotw.org.

[2] Col. McRae took over command of Brig. Gen. Samuel Garland’s brigade after Garland was killed at South Mountain, Sept. 14, 1862. Ripley’s brigade wasn’t at the sunken lane. After the fight in the Cornfield, the brigade withdrew behind Dunkard Church. See Ripley’s O.R. Report and NPS plaque. Cobb’s Legion was from Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ division.

[3] D. H. Hill’s official report, https://antietam.aotw.org/exhibit.php?exhibit_id=32.

[4] Maps don’t pick up the reverse slope. Students need to walk this area.

[5] Brig. Gen. William H. French commanded the Union division. His brigades hit the Confederate line in order: Brig. Gen. Max Weber’s brigade, Col. Dwight Morris’ brigade, and Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s brigade.

[6] If you measure on google maps, the Union 1st Delaware had roughly 4,382 feet to march.

[7] Gordon, 85-90.

[8] William P. Seville, History of the First Regiment, Delaware Volunteers (Wilmington, DE: 1884), 48

[9]“It Appeared As Though Mutual Extermination Would Put a Stop to the Awful Carnage Sharpsburg’s Bloody Lane,” by Robert K. Krick, The Antietam Campaign. Ed. Gary Gallagher, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

[10] The Irish men ripped down a split rail fence, then marched forward, before halting. William H. Osborne, The History of the Twenty-Ninth of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (Boston, MA: 1877), 186. See also Walter Clark, History of Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War, 1861-1865, Vol. 1.

[11] From “Antietam Eyewitness Accounts.” by Scott D. Hartwig. [Online] Available http://www.historynet.com/antietam-eyewitness-accounts.htm. See also, blog, The Sunken Road, American Voices, https://jarosebrock.wordpress.com/maryland-campaign/antietam/the-sunken-road.