Thomas T. Eckert and the Humanity of War

ECW welcomes back guest author Arie De Young.

When considering the American Civil War, one is easily overcome by the overwhelming grandeur and tragedy of the conflict. The expansive view from Lookout Mountain, the haunting photographs of Antietam, the echoing words of the Second Inaugural Address all shape our memory of the war. This is, to borrow Lincoln’s turn of phrase, “altogether fitting and proper.” It is hardly surprising that one of the seminal events in American history has so many dramatic emblems.

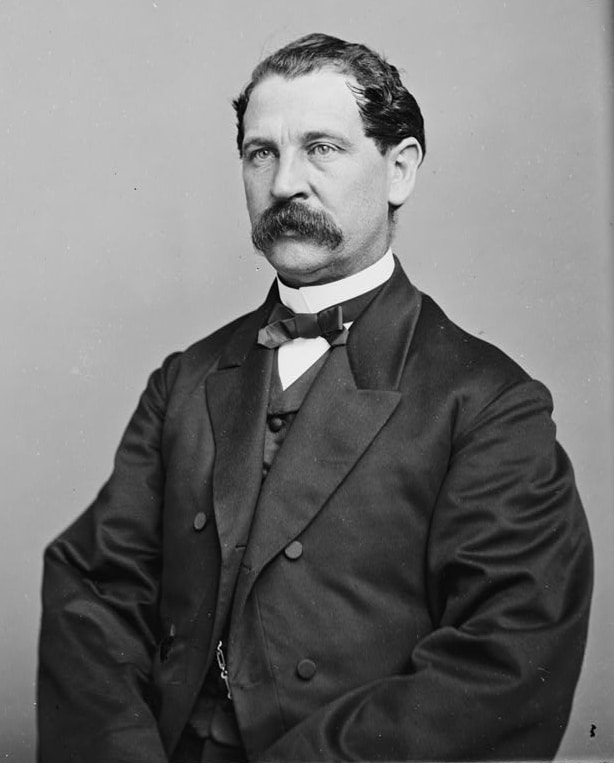

Within the story of the monumental struggle, however, is also an implicit humanity. While we may not be able to truly connect to every experience of the war, we can relate to those who lived through them. Thomas T. Eckert epitomizes this point. He interacted with many of the most famous characters of the era and rose to a position of quiet influence by its conclusion, yet his experiences record stories of these figures in a more human context.

A native of Ohio by birth, his various business ventures led Eckert to manage a North Carolina gold mine. When the Civil War began and North Carolina seceded, Eckert realized the danger of being a northern man in the Confederacy and resolved to return his family to the safety of Ohio.

While he was in Atlanta overseeing some final details for his business affairs, a perilous predicament confirmed his fears. News reached the town of the Confederate defeat at the battle of Rich Mountain and the death of Gen. Robert S. Garnett. A mob assembled in town and brayed for blood, leading to the lynching of an unfortunate Northern-born man.[1]

Afraid that he could be next, Eckert fled to his hotel and noticed a conspicuous name on the register. Thomas Eckert was cousin to George N. Eckert, a former member of the House of Representatives, who during his tenure had boarded with other bachelor congressmen. One roommate was the man whose name was on the hotel register: Alexander H. Stephens, recently elected provisional vice president of the Confederacy. Eckert desperately requested to meet with him, which Stephens granted. Once they were face to face, Stephens warmly greeted his friend’s cousin.

Nevertheless, Eckert’s worst fear soon emerged. The mob discovered him and started swarming the hotel, demanding that he be brought to them. Stephens intervened, telling the leaders, “This man is my guest and friend, and I will be responsible for him. He is all right.” To Eckert’s relief, this proved sufficient to disperse the crowd. With this lucky escape, Eckert continued his journey until he was able to reach the safety of loyal territory.[2]

Among Eckert’s past business ventures had been superintending a telegraph line, making him valuable to the Union war effort. He offered his services to the Union and was sent to Washington D.C. to await orders. There he received the rank of captain and was assigned to the staff of George B. McClellan to take charge of his telegraphs.[3] He worked in the War Department building to oversee the flow of messages to the capital.

While visiting the office of War Department Chief Clerk John Potts, Eckert noticed that some soft-iron pokers had just been purchased for the building. Unimpressed, he announced to Potts that the pokers were of poor quality. To prove his point, he grabbed one of them in his right hand, tensed the muscles in his left forearm, and struck the poker across it. When he lifted the poker, it had been visibly bent.

Perhaps in response to this display, Potts later procured new cast iron pokers. Once again, Eckert denounced them as shoddy. This time, he did not just bend, but actually shattered “four or five” over his forearm. On this occasion, however, President Abraham Lincoln was present. After watching the spectacle, he remarked, “Mr. Potts, you will have to buy a better quality of iron in future if you expect your pokers to stand the test of this young man’s arm.”[4] Lincoln came to appreciate the brawny young officer following the incident, a liking which soon proved fortuitous for the captain.[5]

Meanwhile, in his work as McClellan’s chief of military telegraphy, Eckert developed a reputation for hard work, but also for strictly obeying the letter of his orders. The latter became an issue when the order assigning him as McClellan’s chief of telegraphy instructed him to deliver all military telegrams received in Washington directly to the commanding general. In Eckert’s eyes, this meant excluding the president and secretary of war since they were not explicitly listed.

The negligent Secretary of War Simon Cameron took no issue with this interpretation, but the appointment of Edwin Stanton brought major change. Stanton noticed military telegrams occasionally being reprinted in newspapers, all of which he had not received. This caused his irascible temper to explode. He began a dogged search for the man who he believed was shirking his duties.[6]

When the investigation revealed Eckert as the source of the stoppage, Stanton furiously drafted an order for his dismissal. Receiving word of his imminent fate, Eckert drafted his own letter of resignation in hopes of pre-empting his dismissal, but also sought out an interview with Stanton to discuss the affair. This was granted through the intercession of shared contact, Edward S. Sanford. The meeting began poorly as soon as Eckert and Sanford arrived at Stanton’s office. The secretary of war chose to ignore them for ten full minutes, and when he finally did acknowledge their arrival, it was with a tidal wave of wrathful accusations of incompetence. Eckert’s justifications were furiously cast aside by Stanton, so Eckert offered his exasperated resignation.[7]

Suddenly, he felt a hand on his shoulder. He turned to see Lincoln, who had been on one of his frequent visits to the War Department building and decided to investigate the source of the tirade erupting from Stanton’s office. Having quietly watched the back-and-forth out of view for several minutes, he decided to intervene when Eckert offered to resign. He told Stanton that in all of his many visits to the building, he had never seen Eckert away from his post and that “he had long been in the habit of going to Captain Eckert’s office for news from the front, for encouragement and comfort when he was anxious and depressed.”[8]

Further testimonials from Sanford and Governor John Brough of Ohio sealed Eckert’s deliverance. Impressed by the vehemency of Lincoln’s, Sanford’s, and Brough’s defense, Stanton sat silent for a moment before producing a packet of letters from his desk. Drawing one out, he asked Eckert if it was his written resignation, which it was. Stanton tore it to pieces.

He then produced another letter, the order for Eckert’s dismissal, and tore it to pieces as well. Stanton then said, “I owe you an apology, Captain, for not having gone to General McClellan’s office and seen for myself the situation of affairs. You are no longer Captain Eckert; I shall appoint you major as soon as the commission can be made out, and I shall make you a further acknowledgment in another manner.”[9]

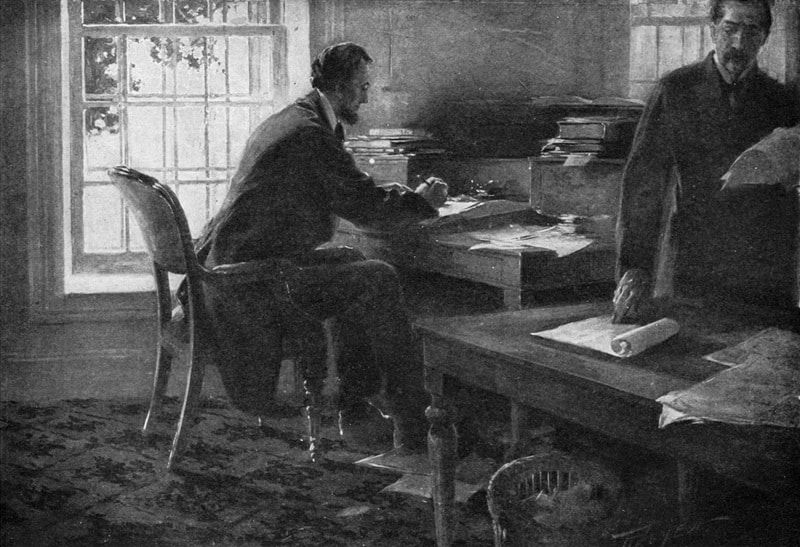

Reconciled with Stanton, Eckert soon became one of his most trusted subordinates. Now a major, he was transferred to control the whole of the War Department’s telegraph office. The position even came with a government horse and carriage as Stanton’s “further acknowledgement”.[10] In this new post, President Lincoln became an even more frequent visitor. Indeed, the Major even claimed that Lincoln drafted the Emancipation Proclamation at his own desk over the course of several visits.[11]

Although that story is debated, Eckert was certainly a witness to another crucial event in the Lincoln presidency: his re-election. Eckert had been the first man to inform Lincoln of his re-nomination in June 1864, so it was only fitting that he was also there on the decisive night in November.[12]

The night began rather inauspiciously for the major; in his haste to reach the War Department’s telegraph office, he had been drenched by rain and had fallen in the mud, much to the amusement of Lincoln and presidential secretary John Hay.[13]

Thereafter, Eckert was in an almost constant state of motion, monitoring the telegraph lines and delivering any transmissions to Lincoln and Stanton in the latter’s office. It was a suspenseful wait, but by midnight it was generally agreed that Lincoln won the race.[14] In celebration, the major procured supper for his guests in the War Department. Hay noted how Lincoln “went awkwardly and hospitably to work shovelling out the fried oysters.”[15]

Ultimately, stories such as these are a reminder that the war, for all its momentous characters and events, was ultimately one enacted by mere humans. Eckert, though a mastermind of the Union’s telegraph lines, was also just a man who was proud of his physical strength, who was sometimes berated by his superiors, and who enjoyed a good fried oyster. He may have lived through extraordinary times, but he remained an ordinary man.

Arie De Young has long been fascinated with the American Civil War, whether it is exploring battlefields, reading books, or attending roundtables. Currently attending Anderson University to achieve his bachelor’s degree, he plans to enter a doctorate program and academia. He has twice been a featured speaker at local Civil War roundtable events.

Endnotes:

[1] David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps During the Civil War (New York: Appleton Century, 1907), 124-126.

[2] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 126-130.

[3] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 130-131.

[4] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 131.

[5] James B. Conroy, Our One Common Country: Abraham Lincoln and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference of 1865 (Guilford: Lyons Press, 2014), 123.

[6] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 132.

[7] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 134-135.

[8] Noah Brooks, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, ed. Michael Burlingame (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998), 251.

[9] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 136-137.

[10] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 137.

[11] Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, 138-142; Todd Brewster, Lincoln’s Gamble: The Tumultuous Six Months That Gave America the Emancipation Proclamation and Changed the Course of the Civil War (New York: Scribner, 2014), 55-58.

[12] John C. Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency (New York: Crown Publishers, 1997), 196.

[13] John Hay, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Diary of John Hay, ed. Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997), 244.

[14] Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, 352-355.

[15] Hay, Inside Lincoln’s White House, 246.

A wonderful portrait of Eckert, stylishly written.

Thank you! I just got a copy of your book, so I am eager to read about one of the most multi-faceted men of this era.

Thanks, Arie. yes, George was indeed multifaceted, and someone who stayed the course on the protection of political and civil liberties his entire life. will you be writing your thesis on Eckert?

Right now, the plan is to focus on a Republican primary for the 1864 U.S. House elections and how it was reflective of divisions within the party at the time, especially heading towards Reconstruction. Hopefully, not only will I get a thesis out of it but one or two Emerging Civil War articles as well.

Interesting. Which primary?

The 1864 Republican primary in Indiana’s 5th congressional district, where incumbent George W. Julian of the radical faction faced a strong challenge from Brigadier General Solomon Meredith of the moderate faction.

Great choice, Julian v. Meredith. Best of luck with it.

Another little gem … nicely done.