The First Deaths of the First Invasion

“Soldiers: You are ordered to cross the frontier and enter upon the soil of Virginia. Your mission is to restore peace and confidence, to protect the majesty of the law, and to rescue our brethren from the grasp of armed traitors.” – Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan[1]

On May 27, 1861, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan pushed his Ohio and Virginia troops across the Ohio River with a goal of securing the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and western Virginia for the Union. While Union forces had established footholds at Arlington Heights and Fortress Monroe, McClellan’s advance marked the first thrust into the interior of Virginia. The Ohio River now effectively represented an international boundary, and McClellan’s advance, an invasion.

In a campaign hallmarked by swift, tactical movement and no significant fighting, accounts of heroic battlefield deaths are almost nonexistent. And those are seemingly the type of deaths that are memorialized in granite or bronze or that leap from the pages of the latest battle or campaign study. But do you know what this invasion had a lot of? Accidental deaths.

There were many (many!) accidents as these guys figured out how to become soldiers. You see men crushed by trains, others who fall off a steamboat and drown, and still others who accidentally shoot themselves or their comrades. Are these deaths any less meaningful than those lives lost on a battlefield or in a prison camp? Brian Steel Wills does an outstanding job of covering this topic, and in fact this very question, in his book Inglorious Passages: Noncombat Deaths in the American Civil War.

We take for granted that regiments often experienced their first losses before ever reaching a battlefield, with disease and accidents frequently recorded as the first deaths in the field. While these may not make for the most engrossing reading in today’s popular history, these deaths were meaningful moments for soldiers on their way to war, sobering men to the reality that soldiering was a dangerous vocation.

These first deaths also allowed an early opportunity for men to grieve. Oftentimes, care was taken to secure and bury the body with military honors or see the remains shipped home to loved ones. The deceased were often editorialized in local newspapers or memorialized in resolutions passed by their comrades. Where today we may see carelessness in the circumstances of their demise, these deaths profoundly impacted and affected their comrades, families, and communities.

Earlier this year, I shared the story of Thomas Baker, a Union enlistee from Hancock County, Virginia, who fell off a steamboat and drowned in the Ohio River on May 21, 1861, while on his way to be mustered into service at Camp Carlile, Virginia. As far as I can tell, Baker is the first Union soldier to lose his life in Virginia during the war, coming three days before the death of Elmer E. Ellsworth at Alexandria.

Only one week later, two men from Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Frederick Ferrell and Alexander D. Mather, became Pittsburgh’s first casualties of the Civil War (excepting perhaps one or two lost by disease), and seemingly the first Union casualties of the war’s first invasion. They were not felled by an enemy’s bullet, but rather by a single accidental gunshot from a comrade.

In early May 1861, several companies of men began organizing at Wheeling in Virginia’s northern panhandle. While the May 23 referendum to ratify Virginia’s ordinance of secession seemed only a formality, these men were instead organizing for Federal service. The fairgrounds on Wheeling Island were christened Camp Carlile, as men began arriving from neighboring counties in Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Benjamin F. Kelley, a former city merchant and militia colonel, was recalled from Philadelphia and elected to lead the newly formed 1st Virginia Infantry.

On May 18, a company of men from Brooke County in Virginia’s northern panhandle arrived at Camp Carlile and were mustered in as Co. G of the 1st Virginia. Described as “hardy looking fellows, capable of enduring any amount of hardship,” the company included several men from Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, where companies and regiments had already reached their quota and sent home many young men anxious to enlist.[2]

The men were not afforded much time for training, and on May 27 orders arrived for the regiment to depart Wheeling. Confederate troops at Grafton had burned two bridges on the mainline of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad near Mannington, and the 1st Virginia was pushed forward to reopen the railroad and drive the Confederates from Grafton. “We were all inexperienced and not skilled in warfare or camp life,” one veteran of Co. G recalled, “and…we left Wheeling, you may say, unorganized, not knowing any of us what a colonel or a regiment was.”[3]

Additional Ohio troops were pushed across the river at Benwood and Parkersburg to move in support of the loyal Virginians, followed by several Indiana regiments a few days later. On arriving at the bridges near Mannington, the 1st Virginia established a camp, appropriately named Camp Burnt Bridge, and began on the repairs to reopen the rail line. The regiment also deployed scouting parties and patrols to scour the countryside for any Confederate troops, especially those responsible for the arson.

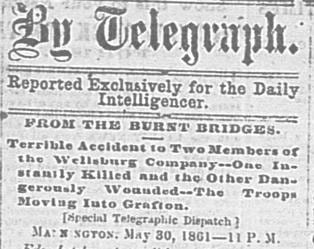

On the evening of May 30, as bridge repairs were nearing completion, one such patrol from Co. G departed camp. Accompanying the men were the company’s two musicians, Frederick Ferrell, drummer, and Alexander D. Mather, fifer. On returning to camp, an accidental gunshot from a comrade struck Ferrell, killing him instantly and passing through his chest before tearing into Mather’s thigh. A testament to the incredibly detailed coverage found in the early months of the war, no less than seven accounts of the incident were covered in three different newspapers. Most of the information in these accounts came secondhand, related to soldiers in camp or by journalists visiting the regiment.

The most detailed account was penned by a fellow member of Co. G. In writing to the Wellsburg Herald, the soldier recalls…

“I now come, Mr. Editor, to the saddest part of my sketch, which was the accidental killing of one of Capt. Kuhn’s men, which occurred on Thursday evening about 4 o’clock, something like a mile from camp. He, in company with several others, among whom were [Jonathan] Armstrong and [Alexander] Murdock [Mather], had been out scouting, and were slowly returning to camp, in single file, down a hill, when the front man, Armstrong, cocked his gun to get a shot at a fox, but not being enabled to do so, placed his gun on his shoulder, cocked. Just as he did so he slipped and fell. His gun went off, the ball striking poor Forrell [Ferrell] in the heart, passing entirely through his body and entering the thigh of Murdock. Forrell [Ferrell] died instantly. Murdock [Mather] is slowly recovering.”[4]

The casualties were conveyed to camp, where shock gave way to indignation and grief. One soldier described the unfortunate Armstrong as “so thoughtless as to carry his piece cocked,” while a visiting journalist chastised “such carelessness on the part of the troops as that from which these men suffered is very reprehensible.” The incident was also picked up by the Pittsburgh press, one paper noting that Ferrell was a resident of Allegheny (modern day North Side neighborhood of Pittsburgh), and that Mather, a resident of Pittsburgh proper, was “doing well.” [5]

Alexander Mather did not ‘do well’ for the remainder of his short life. He applied for a pension several months later (invalid pension application #47!), his surgeon citing the accidental gunshot having made “a severe wound, injuring the muscles of his thigh and thereby making his leg very stiff, and it is with great difficulty he can move about.” Mather’s surgeon declared that the shot injured both the femoral vessels and muscular tissue, not only incapacitating him from further military service, but rendering him totally disabled from providing for himself. Mather died of his wound less than six months later.[6]

Beyond the shooting incident, Ferrell’s funeral was also covered in several newspapers. A soldier in Co. G recorded how…

“Forrell [Ferrell] was buried with the honors of war. The remains were accompanied to the grave by the full brass band of the 16th Ohio Regiment, the commissioned and noncommissioned officers of the different companies, two ministers, and several others, numbering in all about one hundred. Arrived at the burying ground, some four miles below camp, the procession formed and marched to the grave to the music of the dead march. The coffin was covered by the American flag and escorted by a corporal’s guard of soldiers with arms reversed. Arrived at the grave, the body was lowered, when a couple of ladies who were in attendance dropped some fresh flowers into the grave. After which an impressive funeral service was read by one of the ministers, an appropriate prayer pronounced by the other and a round of shots fired over the grave. The procession then re-formed and marched back to the cars and returned to camp.

There were but few dry eyes in all the congregation around the lone stranger’s grave, who had left his friends, family, and home to come and fight for the noble and suffering people, who had not died at the hand of the enemy, but by an unfortunate accident of a friend. He was buried far from home, in a strange land, but many hearts beat warm that day for the family that he left behind him. His burial was one of the most impressive scenes that I ever witnessed, and when I saw strong, bearded men convulsed in tears, their frames shaking with sorrow, I thought that really there were times when tears did become a soldier. Peace to the lone soldier’s ashes, say I.”[7]

A visiting journalist penned another account of the funeral, writing…

“This morning the usual gaiety was not indulged in, and all seemed to be empressed [sic] with the solemnity of a funeral in camp. The body was placed in a coffin draped with the American flag, and borne from the camp to a car, by an escort of eight pall bearers, a guard of honor, the company of which he was a member, the ensign bearing their flag in mourning, and the officers of the other companies on the ground, with numerous others of the volunteers, the band playing the solemn and impressive dead march. The car moving up to Mannington, the procession again formed, the ministers of the place at the head, and moved to the place of burial, where the body was interred with military honors.”[8]

On the return of the funeral cortege to camp, it was found “all bustle and preparation, the bridges having been repaired and the soldiers having received marching orders. We were soon all aboard the train…with three cheers to the Ohio company which had been left behind to guard the bridges from further destruction, and a “Ho! For Grafton!” the trains moved off.”[9]

No family members attempted to claim a pension for Ferrell’s demise, and finding no record of his reburial elsewhere, it’s believed that Ferrell remained buried at Mannington, presumably in an unmarked grave. In the summer of 1868, work crews scoured West Virginia to locate soldier burials for the new national cemetery at Grafton.

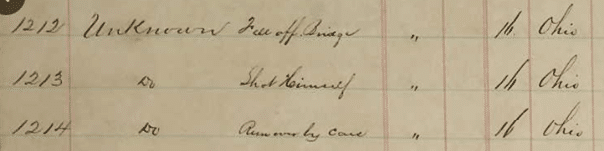

On September 14, three burials were disinterred from the town cemetery at Mannington, seemingly the only soldiers buried in Mannington during the war and ultimately the only burials disinterred from there for the national cemetery. The names of the individuals were unknown, but all three soldiers were identified as having belonged to the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, the regiment that trailed and replaced the 1st Virginia in guarding the bridges in late May 1861. It was perhaps the cemetery sexton or a local resident who recalled the regiment and even recalled the manner of their death. Burial #1212 was recalled as having fallen off a bridge; burial #1213 as having shot himself; and burial #1214 as having been run over by a train.[10]

Here’s the rub: the 16th Ohio did not lose any men in or around Mannington during their 90-day term of service. The regiment lost two men killed in western Virginia (at Corrick’s Ford and St. George); one man by disease (at Rowlesburg, fifty miles distant); and three men (two by disease and one by accident) when the regiment returned to Ohio to be mustered out. The three men buried in Mannington could not, and most certainly did not belong to the 16th Ohio.

Rather, I think there’s a strong likelihood that burial #1213, located in Section F, Range 19, Grave 13 in the Grafton National Cemetery, is in fact Frederick Ferrell of the 1st Virginia Infantry, the soldier recalled as having “shot himself.” With the 1st Virginia having broken camp and moved out within hours of his burial and having been replaced by the 16th Ohio, it’s possible that a local resident or sexton incorrectly recalled the regiment of the decedent. Given that the regiment was attributed as the 16th Ohio, that would seem to indicate that whoever recalled the burials remembered them as having been fairly early in the war, instead of mistakenly attributing later war deaths to an early war regiment.

To be certain, these deaths did not materially impact the outcome of the first invasion or the broader war. The memory of Pittsburgh’s first casualties was soon eclipsed by scores of Pittsburghers dead on battlefields, in hospitals, and in prison camps. The 1st Virginia was praised on returning home without losing “a single man…killed by the enemy,” and a trifling “three or four…lost by accident or disease.” These men were seemingly already a footnote within days of their demise. But when taken together with the other accidental gunshots, drownings, slip-and-falls, and train accidents that were hallmarks of this first invasion of the war, their deaths are emblematic of the rudimentary training and frantic movements of 1861, where the camp was often as deadly as the battlefield.[11]

[1] War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I: Volume II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1880. 49.

[2] “Military Matters,” Daily Intelligencer, May 21, 1861

[3] “Tri-State Reunion,” The Intelligencer, August 26, 1886

[4] “Letter from Grafton,” Wellsburg Herald, June 7, 1861

[5] “Latest from the Road,” Daily Intelligencer, June 1, 1861; “From Grafton,” Daily Intelligencer, June 3, 1861; “Alleghenian Killed,” Pittsburgh Post, June 5, 1861

[6] Alexander Mather pension file, NARA

[7] “Letter from Grafton,” Wellsburg Herald, June 7, 1861

[8] “Latest from the Road,” Daily Intelligencer, June 1, 1861

[9] ibid

[10] Burial Register, Grafton National Cemetery. Accessed via Ancestry.com

[11] “A Great Demonstration,” Daily Intelligencer, August 22, 1861

Great article.

Poignant. And great research.

I don’t know that Gen. Kelley was “recalled”, the Massachusetts native was not a resident of Wheeling for 15 years. The Daily Register wrote on Nov. 9, ’64, “A Surprise-The citizens of the First Ward were yesterday surprised to learn that Brevet Major General B.F. Kelley was a voter in that precinct. Nothwithstanding the fact that Gen. Kelley has not resided in this city within the last fifteen years, and that he has not been in the First Ward half a dozen times within that space of time his ballot was directed to and received by the commissioners at the First Ward poll. When the war began Gen. Kelly (sic) was a resident of Philadelphia, and since that time he has been in the field.” It also begs the question as to just how many non-resident soldiers were allowed to vote in the polls.

McClellan reported to Winfield Scott that most of the Virginia troops such as those in Kelley’s command were mostly from Ohio and Pennsylvania. Contrary to popular history native West Virginians were very reluctant to enlist, Pierpont wrote to Lincoln several times to try and explain the reasons. Col. Evans of the 7th WV wrote to Pierpont- “I am laboring with all my powers to get up volunteers, but I believe Monongalia is the hardest place in the Union to effect anything. We had a very large meeting on monday, at least 2,000 persons present, and Mr. Smith made us a splendid speech; indeed, he excelled himself, but when we called for volunteers after pulling and hauling through the vast crowd, we got 31 men. I am going to have a meeting at camp on saturday, when I think I will get than many more. I went over to Greene County, PA, last week and succeeded in getting a fine company, Capt. Morriss. There was every effort made to prevent them coming to Va….but the men said their interest was with W.Va.; that whilst they were defending W.Va. they were defending their own homes, and so they came.”

We don’t know how many West Virginians were killed or wounded at Philippi, I don’t think a detailed report has been found from Porterfield. In July at Bull Run some local Wheeling men in the Stonewall Brigade were casualities, John Fry, son of Judge J.L. Fry, was killed, George Wilson, son of W.P. Wilson of the First Ward was killed by a shot in the head. William Quarrier was also killed. A young man named Sweeney of East Wheeling, formerly employed at the McLure house, was badly wounded, as also was the son of Rev. Frederick.

Bobbi Lee – Kelley had been a resident of Wheeling until around 1850 when he relocated his children to Philadelphia to be closer to their mother. Kelley received a telegram in Philadelphia on May 22, 1861, requesting that he take command of the regiment forming at Wheeling. I’d consider that being ‘recalled’ to the city, no?

I’m looking specifically at McClellan’s advance from late May – early June, not so much McDowell’s advance and FBR the following month. It makes sense that the Shriver Grays lost several casualties at Manassas given the involvement of Jackson’s regiments.

What an amazing quote from McClellan – “…armed traitors.” It’ s amazing how some in the North misunderstood treason. Treason is when a person or persons attempt to destroy a government; or overthrow a legally-elected government and institute their own; or when they attempt to harm or destroy a country. The Southern Confederacy did none of the above; rather, 11 states, following the Constitution, left the United States to form their own country, not wishing any harm on the former country. And no, it wasn’t about slavery, for five slave states remained in the Union – and a sixth was later added – and the Federal Government didn’t even get around to voting to end slavery for three years and nine months – how come? – and the vote wasn’t ratified until after the war ended. Throughout, slavery remained legal and protected by the Constitution. The South’s cause was legitimate – and real – no, the cause was not “invented” following the war; the myth that the “Lost Cause” was a myth was started by those wishing to establish the myth that the Federal Government’s war was a “Noble Cause” (see the six slaves states that never had to give up slavery during the war) – though secession, however legal – and it remains legal, incidentally – should not have been their choice to resolve the issues at hand. But no, no one committed treason; if they had, they’d’ve been tried for treason, and not a single Confederate soldier or politician was tried for treason. Sorry, Noble Causers, but there is as much evidence of treason in the Civil War as there was Russia Collusion by the Republicans in 2016.