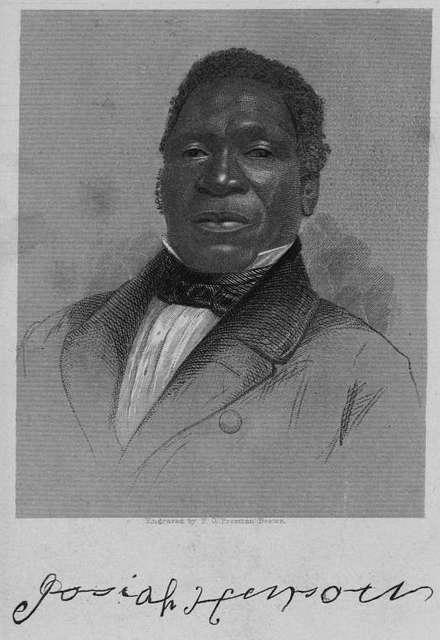

“I’ll use my freedom well”: Josiah Henson’s Life Commemorated at a Maryland Landmark

ECW welcomes back guest author Paula Tarnapol Whitacre.

Alongside a commuter road outside Washington, DC, the antebellum farmhouse of Isaac and Matilda Riley now sits on about five acres of land. That it even remains standing amidst the shopping centers and subdivisions of suburban Montgomery County, Maryland, is astonishing. Property developers in the 1930s saved it because they (mistakenly) believed it was one of the county’s last Revolutionary War-era structures.

It is now best known because of one of its enslaved residents: Josiah Henson. The house forms the core of the Josiah Henson Museum and Park.

Josiah Henson was born around 1789. By the time he died in 1883, he had escaped enslavement in the United States, become a religious and community leader in Canada, published his autobiography in 1849 (with later versions in 1858, 1876, and 1881), and met Queen Victoria and President Rutherford B. Hayes. He also served as a model for Harriet Beecher Stowe when she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Maryland Beginnings

At age six, Henson was separated from his family and sold at auction. Alone, weak and terrified, he became ill and was judged “unlikely to recover” (not that any medical care was provided to reverse that fate). [1] Isaac Riley, who had purchased his mother at the same auction, acquired him “for a trifling rate.”

The reunion with his mother saved his life. Despite hard labor and inadequate food, shelter, and clothing, “I grew to be a robust and vigorous lad,” he recalled. By the time Henson was in his early twenties, the usually drunk or gambling Riley relied on him as farm superintendent. This position gave Henson more autonomy than most enslaved people; for example, to travel to conduct business. He learned to negotiate the line between meeting Riley’s demands and directing additional food and comforts to the enslaved people who labored for the benefit of the Riley family. He also began to preach among the county’s Black communities and, in 1821, married Charlotte Stevenson.

Unlikely Journeys

In 1825, Riley was mired in debt and lawsuits. He hatched a plan to send twenty-two enslaved men, women, and children—his most valuable “property”—beyond the jurisdiction of Maryland courts to his brother Amos’s farm near Owensboro, Kentucky. Incredibly, he put Henson in charge of transporting the group on the 650-mile journey, in what historian Jamie Ferguson Kuhns characterized as “a life-changing, and for most, disastrous chapter in their lives.”[2] They passed through Ohio, a non-slave state, before dipping south into Kentucky. The Ohioans they met urged and pled with Henson to liberate himself and the group while they had the opportunity. He felt he had to fulfill his obligation, which meant keeping his family and eighteen other people in bondage.

That decision haunted Henson for the rest of his life. Riley reneged on his promise to keep the Maryland group together. He sold everyone except the Hensons to plantations in Mississippi where conditions were reportedly far harsher than in Maryland or Kentucky. “Often since that day has my soul been pierced with bitter anguish at the thought of having been thus instrumental in consigning to the infernal bondage of slavery, so many of my fellow-beings,” he wrote.

And yet, freedom beckoned. When a visiting abolitionist-minded minister discreetly offered to help Henson manumit himself (i.e., purchase his own legal freedom), Henson decided to press his case with Isaac.[3] He convinced Amos to allow him to return to Maryland after the 1828 harvest season. With initial help from the minister, Henson raised money through preaching and donations along the route to Maryland. Riley’s farm had greatly deteriorated. Riley had not bothered to notify Henson that his beloved mother had died. He agreed to a price of $450, took Henson’s money, but doctored the paperwork (which Henson could not read). Back in Kentucky, Amos reviewed the document and gleefully told Henson the price for his freedom had more than doubled. He was as enslaved as when he had left.

Worse, the Rileys decided to sell Henson south. Forced to accompany Amos’s son on a trip to New Orleans, ostensibly to sell farm goods, he was saved only because the son became critically ill and needed Henson’s help to return to Kentucky.

Escape to Canada

The manumission treachery and the near-sale convinced Henson to act. “I determined to make my escape to Canada,” he wrote. With time, he persuaded Charlotte to take the life-or-death risk with their four sons. Henson’s later descriptions of depleted food and water, exhaustion, cold rain, and constant vigilance for slave-catchers and wild animals are harrowing even knowing the successful outcome. A ship captain took them on the last leg to Canada. After the six-week ordeal, “when I got to the Canada side, on the morning of the 28th of October, 1830, my first impulse was to throw myself on the ground.”

Henson had keen survival skills, and he applied them well in Canada. He quickly found work and started to buy livestock. His oldest son, legally able to attend school for the first time, taught him to read. He organized a group of Black families to co-purchase land in southwestern Ontario. Coincidentally but aptly, the township they located was called Dawn.[4]

By the 1840s, residents farmed the land, established a school, and operated a sawmill and other businesses. Not surprisingly for any community, Dawn had its share of economic and interpersonal problems, but it was celebrated in the abolitionist press. According to biographer Jared Brock, “Josiah was the spiritual and celebrity leader of Dawn, but the settlement was far bigger than any one person.”[5] With this visibility, he traveled widely to conduct business, orate, and fundraise for the school. He attended the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, where he met Queen Victoria. And, at great peril, he returned to Kentucky to lead 118 enslaved people into Canada.

In 1849, Henson collaborated with a Boston abolitionist on his autobiography. Frederick Douglass’s 1845 narrative showed the market for the first-hand experiences of the formerly enslaved. Initially, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada had limited sales, but Harriet Beecher Stowe read it. She invited Henson to visit her home, where “she was deeply interested in the story of my life and misfortunes, and had me narrate its details to her.”

The Link to Uncle Tom

Over the years, how Stowe drew from Henson’s life to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought Henson both fame and criticism. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became a lightning rod of attention. Northerners made it a mega best-seller; Southerners vilified it as impossibly false. In 1853, when Stowe documented her sources in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she acknowledged Henson’s life as one (not the) inspiration for Tom and for some of the incidents in the novel. Henson, for his part, wrote he was proud his life contributed to the impactful book.

The attention greatly raised his profile. His autobiographies published in the 1870s and 1880s inserted “Uncle Tom” into their titles. But fame was double-edged. Uncle Tom has become a polarizing figure over the years, and he had to clarify that he was not that fictional character. Indeed, he accomplished far more than his association with Stowe’s novel.

Full Circle: Back to Maryland

Henson returned to Montgomery County and visited Riley’s widow in 1878. He later said it was the only time he entered the house through the front door, not an entrance designated for the enslaved workers.

A series of property transactions in the 1900s decreased the acreage, but kept the house standing. The “legend of Uncle Tom’s old home” circulated locally, although the accuracy morphed through the years.[6]

In 2006, the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission purchased the property from its last private owner. The site now offers a visitors center, exhibits in and around the restored house, and educational programs.[7] Archaeology that began in 2010 continues to reveal the world of Josiah Henson.

Paula Tarnapol Whitacre has written a book about Alexandria during the Civil War and Reconstruction under contract with Georgetown University Press, with expected publication in 2026. She previously published a biography of abolitionist Julia Wilbur titled A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time: Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (Potomac Books, 2017). Her website is at www.paulawhitacre.com.

Endnotes

[1] Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (Arthur D. Phelps, 1849). Unless cited otherwise, direct quotes in this post come from the narrative, now in the public domain, including at the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.21827?st=grid).

[2] Jamie Ferguson Kuhns, Sharp Flashes of Lighting Come from Dark Clouds: The Life of Josiah Henson (Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, 2018).

[3] Henson did not identify the minister but described him as a “white man of some reputation.”

[4] The former settlement is part of Dresden, where the Ontario Heritage Trust maintains the Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History. See https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/properties/josiah-henson-museum

[5] Jared Brock, The Road to Dawn: Josiah Henson and the Story that Sparked the Civil War (Hachette Book Group, 2018).

[6] One such semi-accurate version, from the 1930s, is reprinted in Kuhns, pg. 161.

[7] For more information on the site, see https://montgomeryparks.org/parks-and-trails/josiah-henson-museum-and-park/

Thank you for bringing this interesting character to light. Question about his efforts in bringing 118 enslaved to freedom: how many journeys did he make into Kentucky?

That’s a good question without a definitive answer, unfortunately. From his autobiographies and the book by Jamie Ferguson Kuhns, he led at least three “missions” in the 1830s. One group, he said in the 1881 version of his autobiography, consisted of thirty people.

Quite gutsy. And the logistics of moving such a large group must have been challenging.