A Baseball Game on Hilton Head

ECW welcomes back guest author Walt Young.

Readers of this blog, especially if they are baseball fans, will likely know the role the Civil War had in spreading America’s national pastime across the nation (see part 1 and part 2 of this look at baseball in the Civil War). Many will know the story of how Abner Doubleday, a well-known U.S. general, was eventually credited with having “invented” the game.

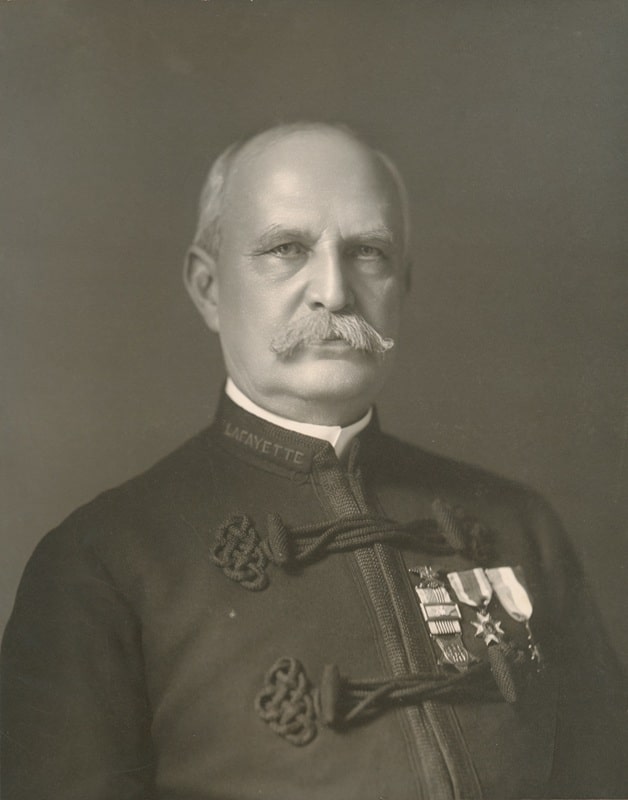

However, fewer today have heard of Abraham G. Mills, who helped to create Doubleday’s dubious claim to baseball fame. To learn about Mills, and his ability to craft a story, we can step back in history to Christmas Day of 1862 and a baseball game on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina.

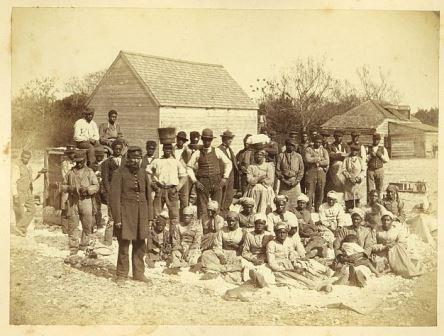

By the time of the game in question, Hilton Head had been in United States hands for over a year. The U.S. Navy captured the island, along with nearby Beaufort and Port Royal, in November 1861 and transformed the region into the headquarters of the Department of the South. One of the first U.S. regimental newspapers in the southern states, the Port Royal-based New South, published its first issue in March 1862.

As a result of Hilton Head’s role in U.S. coastal activities, regiments from across the country passed through the island. One was the 165th New York, also known as the 2nd Duryee Zouaves. The regiment was recruited during the fall of 1862 and left its home state in early December. Even though their destination was New Orleans, their presence in Beaufort is recorded by the New South on December 27. One soldier in the 165th NY was Abraham G. Mills, who mustered into the regiment as a sergeant.[1]

Other regiments spent extensive time on duty on Hilton Head. The 47th New York had been present at the island’s capture and spent much of 1862 involved in operations near Savannah and Charleston, including the capture of Fort Pulaski. They remained on Hilton Head between July of 1862 and April of 1863.[2]

At Christmas of 1862, the 47th NY stars in the New South’s depiction of holiday festivities:

“In the camp of the 47th Regiment New York Volunteers the day was made the occasion of a flag raising at which the 2nd Battalion of Duryea Zouaves, under command of Lt. Col. Abel Smith, assisted. Previous to the ceremony of raising the flag the Zouaves were reviewed by Col. Frazer of the Forty-Seventh … At the Provost Marshal’s Quarters there were absurd and laughable sports among the men, and a ball match between the ‘Van Brunt’ and ‘Frazer’ Base ball clubs, which resulted in a victory for the latter; and in the evening the Provost Guard minstrels entertained a large audience with songs and dances.”[3]

The names of the two teams, “Van Brunt” and “Frazer,” are two of the officers of the 47th, George B. Van Brunt and James L. Fraser. While Fraser’s name has a slightly different spelling than the newspaper records, we can identify him as the colonel in question based on the NPS Soldiers and Sailors database. While the 2nd Duryee Zouaves are in the right place for the game, the 47th is clearly the driving force of the game in this contemporary account.

The story of the game remained largely out of the public view for the next 50 years. In 1911, however, a version of the game’s story appeared in America’s National Game, a book by baseball renaissance man Al Spalding.

A former player, executive, and sporting goods magnate, Spalding was attempting to write a history of baseball. He had long been a proponent of the idea that baseball was “of modern and purely American origin” and had proposed a commission between 1905-07 to tell the story of the game’s origins. The head of this commission was Abraham G. Mills, whom Spalding describes as “an enthusiastic ball player before and during the Civil War, and the third President of the National League.”[4]

The Mills Commission supported the position of its benefactor, Spalding. They received a letter from Abner Graves, a Colorado miner who claimed to see Abner Doubleday invent baseball in Cooperstown, New York around 1839. Despite Graves’ age at the time of the alleged invention (5 years old), they supported the story, giving the deceased Doubleday an afterlife as the founder of baseball. Spalding quotes Mills, in his report, as saying that he and Doubleday were part of the same GAR post and that Mills had served as a guard of honor when Doubleday’s body lay in state in New York City Hall.[5] Most historians today reject the commission’s conclusions.[6]

Unsurprisingly, Spalding’s 1911 book agrees with the Mills Commission’s findings. However, Mills also plays a starring role in Spalding’s account of the Hilton Head Island game.

From Spalding: “However, it is of record that many games of Base Ball were played by soldiers during the war. On Christmas Day, December 25th, 1862, a team from the 165th New York Volunteer Infantry, Duryea’s Zouaves, engaged a picked nine from other Union regiments in that army. The game was witnessed by about 40,000 soldiers. It was played at Hilton Head, South Carolina, and was discussed for many a week thereafter. Among those participating in the game was Mr. A.G. Mills, of New York City, afterwards President of the National League, and to him I am indebted for the interesting incident.”[7]

As opposed to the Doubleday story, the broad facts of this story – time, place, and evidence of a baseball game – are verified by a contemporary source. However, the Spalding/Mills version of the story has an entirely different protagonist than the New South’s contemporary account. The New South depicts a game between two teams named after officers of the 47th NY, with the Zouaves present and participating in the day’s festivities. The Spalding/Mills version has the 165th NY/Zouaves field a team of their own, with their opponents drawn from “other Union regiments in that army.”

It is possible to reconcile the stories to a point. Colonel Fraser had reviewed the Zouaves that morning, so they could have fallen into the team named for him. Alternatively, they could have departed after the flag ceremony and played their own game – but no second game was mentioned in the New South article, and so likely would not have drawn the 40,000 spectators which Spalding/Mills mention.

The Spalding/Mills version of the Hilton Head game story was reprinted in newspapers throughout the 1910s and 1920s. When the game is written about today, this is generally the version relied on. The New South was only printed until 1867, and its version of the story seems to have been forgotten until the paper was digitized in the 21st century.

Historians of the Civil War are used to analyzing primary sources, including post-war accounts of battles and decisions. Soldiers remembering the war can fit their memories into a comforting narrative, place themselves at the center of memorable events which they witnessed, and align credit for triumphs in ways which fit their biases. None of this makes them malicious; it just requires the reader to fit their accounts into a puzzle and accept when the truth of a story may be incomplete.

The Hilton Head baseball story may be just such a case, in which the most well-known participant in the event is the person who gets to tell the story. On Hilton Head, the stakes were low. From battlefields across the country to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, the writings of self-interested parties had long-lasting impacts on how we tell our most important stories.

Walt Young has loved learning about the Civil War since visiting Harpers Ferry, West Virginia on a childhood trip. When not studying history, he enjoys hikes, mysteries, and Baltimore sports.

Endnotes:

[1] New York in the War of the Rebellion, 3rd Edition. Ed. Frederick Phisterer. Albany, 2012. Cited by “165th Infantry Regiment”, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, 2025; “Mills, Abraham G.” NPS Soldiers and Sailors Database. Accessed via nps.gov: https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-soldiers-detail.htm?soldierId=E0FB5CBB-DC7A-DF11-BF36-B8AC6F5D926A.

[2] “Union New York Volunteers: 47th Regiment, New York Infantry.” NPS Soldiers and Sailors Database. Accessed via nps.gov: https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UNY0047RI.

[3] “Christmas Day.” The New South, 27 Dec. 1862, p. 3. Accessed via newspapers.com: https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-new-south-baseball-on-hilton-head-is/165072742/

[4] Spalding, Albert G. America’s National Game. New York, 1911. P. 20.

[5] Spalding, America’s National Game, 20.

[6] Thorn, John. “Abner Doubleday – Spring 1839.” Our Game, 2025 Sep. 8. Accessed via mlblogs.com: https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/abner-doubleday-spring-1839-443f54606189. (Note: Thorn is the official historian of Major League Baseball and the author of the book Baseball in the Garden of Eden. I have chosen this brief blog post as a summation of the now standard historical view of the Mills Commission’s work).

[7] Spalding, America’s National Game, 95-96.

Great story to go with the World Series this week–thanks!