The Strange Case of George Dedlow Revisited

ECW welcomes guest author Thomas F. Curran.

The fictional short story of George Dedlow, circulated in the wake of the American Civil War, revealed in clear detail the trauma of a soldier who lost not one, but all four limbs in the conflict. Despite the account’s realistic portrayal, however, its narrative takes an unexpected supernatural turn at the end, one that many readers believed to be quite true.

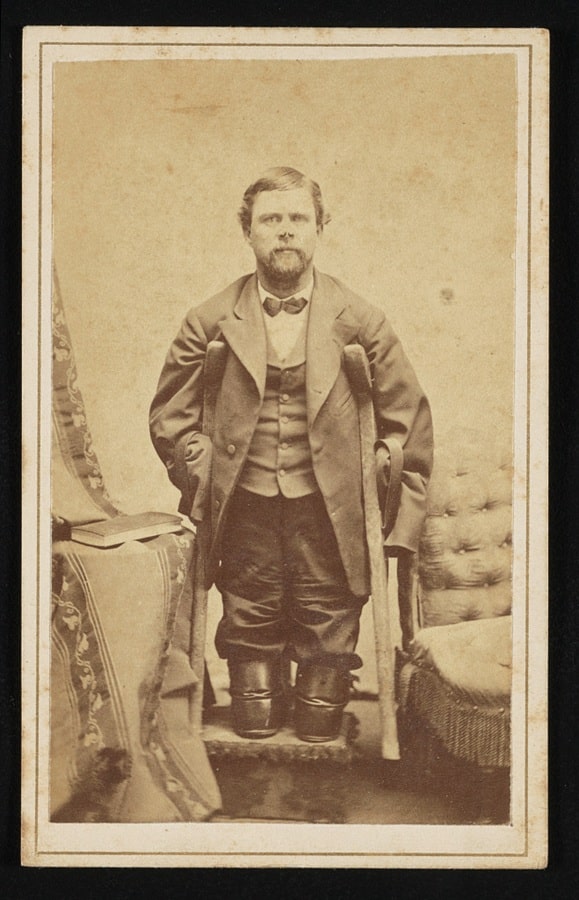

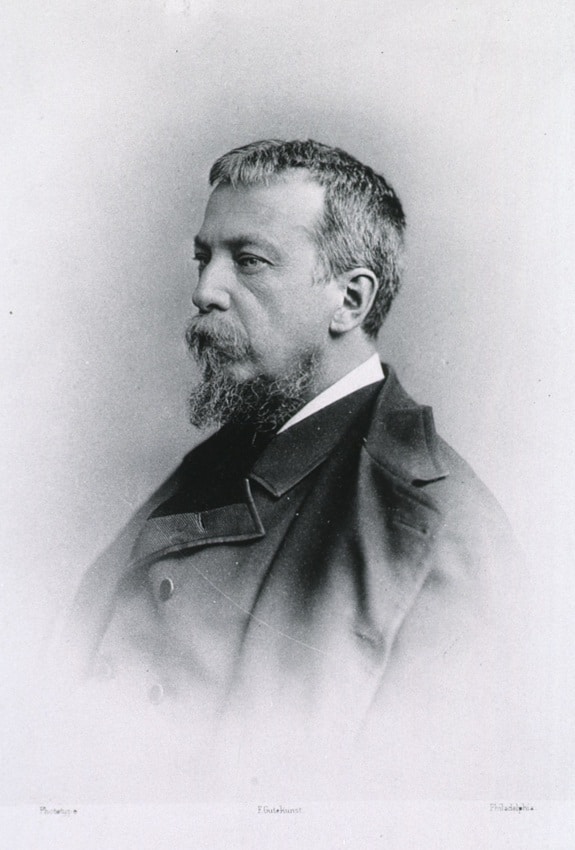

In 1866, Silas Weir Mitchell published a short story in The Atlantic Monthly called “The Case of George Dedlow.”[1] Mitchell, a physician who treated Union soldiers with war-related nervous disorders during the war, studied amputees and identified the condition known as phantom limb pain.[2] The co-author of the 1864 medical tome Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves,[3] the good doctor wrote this anonymously published story about a young prewar doctor, George Dedlow, who as a lieutenant in an Indiana infantry regiment lost both arms and legs while serving in Tennessee.

The story is told in three parts. First, Dedlow joined the Union army, was wounded in both arms during a guerrilla ambush, and lost one arm while under the care of Confederate doctors as a prisoner. After undergoing a prisoner exchange and still not completely recovered, Dedlow rejoined his regiment, only to lose both legs to amputation after receiving wounds at the battle of Chickamauga. He then lost his last extant limb to gangrene while recuperating from his other removals.

After this, Dedlow was sent to a hospital in Philadelphia— the so-called “Stump Hospital” specializing in treating amputees—and then to the United States Army Hospital for Injuries and Diseases of the Nervous System in Washington, D.C. This brings us to the second section of the story, where narrator Dedlow described his continued sensations of feelings in the limbs that are no longer attached to him, what Dr. Mitchell as a scientist famously dubbed “Phantom Limbs.”

Thus far, Mitchell’s tale is compelling, well written, and very dramatic. His prose exposes the trials and tribulations of those soldiers who literally gave a piece, or pieces, of themselves in the fight to preserve the Union. It is in the last section of the essay that “George Dedlow” turns from the serious to the humorously absurd, as Mitchell takes a swipe at the popular 19th-century spiritualist movement.[4]

The armless, legless Dedlow was invited by a fellow patient to visit “the New Church,” where one was “able to turn away from earthly things and hold converse daily with the great and good who have left this here world.” Along with those seeking to reach the dearly departed, at the church Dedlow encountered a quack doctor, described as “a flabby man, with ill-marked, baggy features and injected eyes,” and “Sister Euphemia,” a female-authoress “of two somewhat feeble novels.” Dedlow further describes her as a “pallid, care-worn young woman with very red lips, and large brown eyes” who has left her husband to devote herself to the quack.

Then there is the star of the event, a medium named Brink, a jewelry-clad, side-whiskered charlatan with a large nose and full lips.[5] As the meeting progressed, we are told, Brink was able to communicate with the deceased young son of a woman in mourning clothes. Overwhelmed, the mother was carried from the room. The medium then contacted lost loved ones of several others in attendance through a series of raps supposedly emanating from the afterworld. Two raps signifies “yes.”

The attention finally turned to George Dedlow, with the medium now assisted by the quack doctor and his big-eyed devotee. The doctor instructed Dedlow to think of a spirit who he wished to contact from the beyond. Struck by an idea, the skeptical Dedlow agreed, and after a pause more rapping commenced. Two raps, then two raps.

The quack posited that there must be two spirits present. Then the rapping counted out two sets of numbers, 3-4-8-6, then 3-4-8-7. In a moment worthy of the ending of a Twilight Zone episode, Dedlow cried out “Good gracious! … they are my legs – my legs!” It turns out that Dedlow decided to try to make contact with his lost lower limbs. The raps represent the numbers assigned by the United States Army Medical Museum to his severed legs, now part of the museum’s collection.

Where Rod Serling would have wrapped up the story with a sardonic coda, Mitchell carried the narrative a bit too far. Feeling “reindividualized,” Dedlow then “arose, and staggering a little, walked across the room on limbs invisible” to him or to the others. While the staggering may have been a product of disuse of the legs for so long, it is also true that the museum had been storing them in a vat of alcohol, thus the limbs may have been a bit tipsy. After a few seconds the unseen legs disappeared, and Dedlow sank safely to the ground, after which he “fainted and rolled over senseless.”[6]

In the wake of the piece’s publication, an outpouring of sympathy and support emerged for the fictional George Dedlow. People contacted or visited the real “Stump Hospital” on the outskirts of Philadelphia trying to locate “the unhappy victim.” Others attempted to raise money for his benefit.

Despite the phantasmagoric ending, people believed the tale to be true and Dedlow to be real. In 1871, Mitchell issued a disclaimer of sorts, not in The Atlantic Monthly, but rather as a passing mention in an essay on phantom limb pain that appeared in a different popular magazine.

Never taking credit for writing the essay on Dedlow, Mitchell noted that the essay’s author “could never have conceived it possible that his humorous sketch, with its absurd conclusion, would for a moment mislead anyone.” It did. In an age when many clung to the idea that the living could contact the dead, especially in light of the death toll of the Civil War, many may have seen the George Dedlow story as evidence that loved ones lost were just a rap or two away.[7]

Thomas F. Curran is author of Funny Thing About the Civil War: The Humor of an American Tragedy (2023), Women Making War: Female Confederate Prisoners and Union Military Justice (2020), and Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement (2003). He teaches American history at Cor Jesu Academy in St. Louis, Missouri.

Endnotes:

[1] “The Case of George Dedlow,” The Atlantic Monthly 18 (July 1866), 1-11. The essay also appears in S. Weir Mitchell, The Autobiography of a Quack and The Case of George Dedlow (New York: The Century Co., 1900), 113-149. Quotes are from the latter version.

[2] Frank R. Freemon, “The First Neurological Research Center: Turner’s Lan Hospital during the American Civil War,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 2 (1993): 135-142.

[3] S. Weir Mitchell, George R. Morehead, and William W. Keen, Gunshot Wounds, and Other Injuries of Nerves (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Co., 1864).

[4] Bret E. Carroll, Spiritualism in Antebellum America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997).

[5] “The Case of George Dedlow,” 141-44.

[6] “The Case of George Dedlow,” 148.

[7] Robert I. Goler, “Loss and the Persistence of Memory: ‘The Case of George Dedlow’ and Disabled Civil War Veterans,” Literature and Medicine 23 (Spring 2004): 160-83; S. Weir Mitchell, “Phantom Limbs,” Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science 8 (December 1871), 563-69, quote on 564; Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 180-85. Mitchell later acknowledged that he wrote the essay, but he insisted that he only shared it with a friend, not expecting that person to pass it on to Edward Everett Hale, the editor of The Atlantic, who published it. See “Introduction,” The Autobiography of a Quack, ix.

Very interesting! Perfect for the season

Excellent piece – well done! Yes, so reminiscent of The Twilight Zone and Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” Does anyone know of other Civil War stories that were adapted by Rod Serling for The Twilight Zone?

To my knowledge, The Twilight Zone aired four Civil War-related stories. In “Back There,” a time traveler tries to stop the Lincoln assassination. “The Passersby” portrays soldiers, who are all dead, passing by a burned out mansion at the end of the war and a wife anxiously awaiting her husband. Confederate soldiers face the dilemma of whether or not to use the assistance of the devil to win a battle, Gettysburg, in “Still Valley.” And, of course, the Zone presented a special episode televising the award-winning short film, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek.” Many of Ambrose Bierce’s short stories would have made for great shows, but only this one made it.

Thanks, Tom, all interesting to know. Will look up those other three Twilight Zone episodes you mention. And there’s more. “Occurrence,” the only non-Twilight Zone produced film to be aired on the show, in 1964 with a special introduction by Rod Serling, was written/directed by Robert Enrico (adapted from the Ambrose Bierce short story) in France in 1961, and was part of a trilogy released as a feature-length film, “Au coeur de la vie,” containing two other Ambrose Bierce short stories about the Civil War, “Chickamauga” and “The Mocking-Bird”. Will make a point of finding all of these to watch!