“Spherical Case & Shell at 800 Yds.”: 5th Maine Battery at Gettysburg Theological Seminary

Captain Greenlief Thurlow Stevens of the 5th Maine Battery first heard the battle’s roar while riding on the Emmitsburg Road toward Gettysburg “between ten and eleven o’clock A.M.” on July 1, 1863. “In the vicinity of the ‘Peach Orchard,’” the battery “turned off … to the west … and marched across the fields” toward “a furious conflict then raging between the enemy” and Union cavalry and infantry, Stevens said.

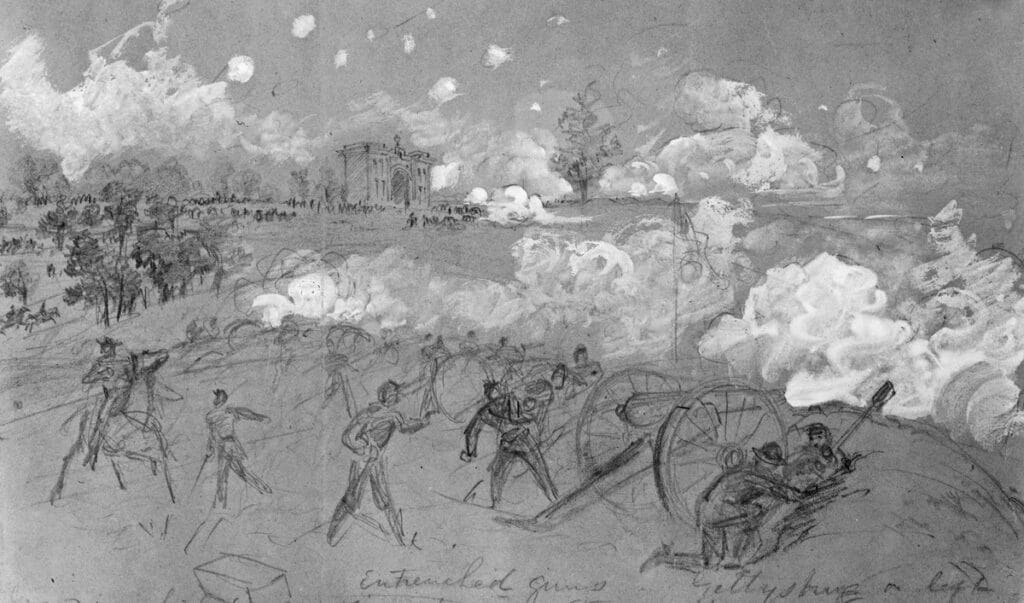

“On reaching a piece of lowland” the battery “made ready for action,” and up rode an aide from Col. Charles P. Wainwright with orders for Stevens to deploy his “six light 12-pounders.” Stevens unlimbered them “in a little growth of trees along an old stone wall or pile of stones a short distance south of the Theological Seminary,” but did “no firing in that position.”

Slightly past 2 p.m., orders repositioned the 5th Maine Battery about 150 feet north of Schmucker Hall and a short distance south of the Chambersburg Pike. “There was not room for all our six guns” in the new position, Stevens noticed, so “I ran some of them in between the [four 3-inch] guns” of Battery B, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, commanded by Capt. James Cooper. The 10 cannons of Battery B and the 5th Maine Battery stood “hardly five yards apart,” Stevens said.

Squeezed into the artillery line, one 5th Maine gun crew faced a seminary outbuilding, perhaps a privy. “I ordered it blown away[,] which was immediately done,” probably with a solid shot, Stevens said. “That gun continued to fire through the hole made in the building until the whole line was forced to retire.”

Captain Gilbert Reynolds pulled his Battery L, 1st New York Light Artillery and its six 3-inch ordnance rifles back to Seminary Ridge. Two sections unlimbered south near the Hagerstown Road, and Reynolds placed his third section at the Chambersburg Pike, just north of the 5th Maine Battery.

Gazing westward, Stevens realized, “The whole line of battle from right to left was then one continuous blaze of fire.” With “the thin blue smoke of the infantry” obscuring the slight dip between Seminary and McPherson ridges, gunners found “it difficult to distinguish friend from foe. Our infantry, by the overwhelming numbers of the enemy, five to one, were forced back.”

Targeting Confederate regiments crossing McPherson Ridge south of the Chambersburg Pike, the 5th Maine gunners “opened fire with spherical case & shell at 800 yds.,” reported 1st Lt. Edward Whittier, Stevens’ second-in-command.

As his Confederate division advanced toward Gettysburg, Maj. Gen. William Dorsey Pender deployed his brigades in line perpendicular to and south of the Chambersburg Pike. The North Carolina brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Scales moved on the division’s far left, “with my left [flank] resting upon the turnpike,” Scales later reported. His men moved “in good order … under a pretty severe artillery fire from the enemy in my front.”

The Tar Heels ascended the western slope of McPherson Ridge, “crossed the ridge, and commenced the descent [directly] opposite the theological seminary,” Scales said. Union artillery caught the North Carolinians on the down slope. “Here the brigade encountered a most terrific fire of grape and shell on our flank, and grape and musketry in our front.”

Although “every discharge made sad havoc in our line,” onward came the Confederates, running “at a double-quick until we reached the bottom” of McPherson Ridge, Scales said. Now 75 yards past the ridge’s summit and “about the same distance from the college, in our front,” his men repeatedly closed ranks and kept coming.

The Maine, New York, and Pennsylvania gunners eviscerated Scales’ Brigade. Catching double charges of canister, the Tar Heels tightened their lines as the file-closers (those still on their feet) filled the gaps. Fallen North Carolinians littered the McPherson Ridge slope and the ground nearer the theological seminary. “Here I received a painful [leg] wound from a piece of shell, and was disabled,” reported Scales. “Our line had broken up, and now only a squad here and there marked the places where regiments had rested.”

He transferred brigade command to Col. William L. J. Lowrance of the 34th North Carolina. He found “in all about 500 men” still on their feet. “In this depressed, dilapidated, and almost unorganized conditions, I took command,” Lowrance said.

Union infantry fell back to Seminary Ridge. Colonel Roy Stone and the survivors of his 2nd Brigade (Second Bucktails) flowed between Stevens’ and Cooper’s guns and reformed behind them. As the Pennsylvanians came past, Stevens found “some of them crouching under the very muzzles of the guns of the Fifth Battery to avoid its fire.”

“In the face of the most destructive fire that could be put forth from the three batteries in position” near Schmucker Hall, Confederate infantry absorbed the punishment and wrapped around the Union position along Seminary Ridge, Edward Whittier said. Finally “dislodging the infantry in the grove covering our left flank,” the Southern troops drove the 1st Division from the field, he noted.

“In less than ten minutes after I was disabled and left the field, the enemy, as I learn, gave way, and the brigade, with the balance of the division, pursued them to the town of Gettysburg,” Albert Scales later wrote.

Orders to withdraw came from James Wadsworth around 5 p.m. Stevens brought his battery to the Chambersburg Pike, where the gunners swung their horse teams right (east) to mingle with retreating Union infantry. Confederate skirmishers now “overlapped our retreating columns and opened a severe fire within fifty yards” of the road, Stevens reported. “The batteries now broke into a trot.”

Traveling “with the balance of Coopers Battery,” the 5th Maine Battery retreated into Gettysburg, Stevens said. The Mainers “struck Baltimore Street and followed that street … until we reached Cemetery Hill opposite” the Evergreen Cemetery gate.

As the 5th Maine Battery crested the hill, Stevens saw Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, sent forward by George Gordon Meade to assume command at Gettysburg. Hancock and his aides directed arriving units into Evergreen Cemetery “or to the South,” Stevens noticed.

When Hancock “called for the ‘Capt of that brass battery,’ I galloped up to him and reported,” he recalled. Hancock ordered the 5th Maine Battery onto the western slope of Culp’s Hill overlooking Cemetery Hill. From there the battery could “stop the enemy from coming up through” a ravine that ran transversely beneath Cemetery Hill’s eastern slope.

Separating “each gun and caisson … from Cooper’s battery,” Stevens moved southeast along the Baltimore Pike, turned east into a lane, and climbed to “a knoll at the westerly extremity of Culp’s Hill. This position commanded completely the easterly slope of Cemetery Hill and the ravine at the north.”

After banging away “at intervals” at visible Confederates “until dark,” the 5th Maine gunners settled in for the night. Downing hot coffee and hardtack, the “tired and exhausted” gunners “wrapped their blankets about them and camped down beside their guns and horses for a little rest, with mother earth for a pillow,” Stevens commented.

You can watch a video of the 5th Maine Battery monument here.

Sources: Stevens’ Fifth Maine Battery, Maine at Gettysburg, The Lakeside Press, Portland, ME, 1898, pp. 82-91, 100; Greenlief T. Stevens letter to Seldon Connor, September 20, 1889, Maine State Archives; 1st Lt. Edward N. Whittier report to Maine Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, August 2, 1863, MSA; Brig. Gen. Alfred M. Scales, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. 27, Part 2, No. 560, pp. 669-700; Col. William L.J. Lowrance, OR, Vol. 27, Part 2, No. 561, p. 671

“A granite monument and a 12-pounder bronze Napoleon mark the site where Stevens’ 5th Maine Battery fought advancing Confederate infantry on July 1, 1863. The monument and cannon are near Schmucker Hall on Seminary Ridge” – interesting enough its a Model 1841 Six pound gun that has been modified into a False Napoleon. Of the five guns marking the 5th Maines battery on McKnights (Stevens) Hill only one is a true Napoleon gun. Is position is on the right side of the road. The remainder of the guns are all M1841’s made into False Napoleons.

Excellent description of the action during the afternoon of July 1. Scales’ brigade suffered badly.