John Pelham’s Opponents at Fredericksburg

In some retellings of famous battlefield moments, the heroes in the spotlight fight nameless, faceless shadowy enemies. For example, Major John Pelham of the Stuart Horse Artillery dominates the legends and the spotlight at the battle of Fredericksburg for the brief opening of the combat on December 13, 1862. Some versions give the impression that Pelham single-handedly fired the cannon he positioned on the Union infantry’s flank. In reality, skilled gunners did much of the work and took the casualties, too. Also, there were two Confederate cannons that advanced: one with Pelham, and one sent later that was destroyed after only firing a few rounds.

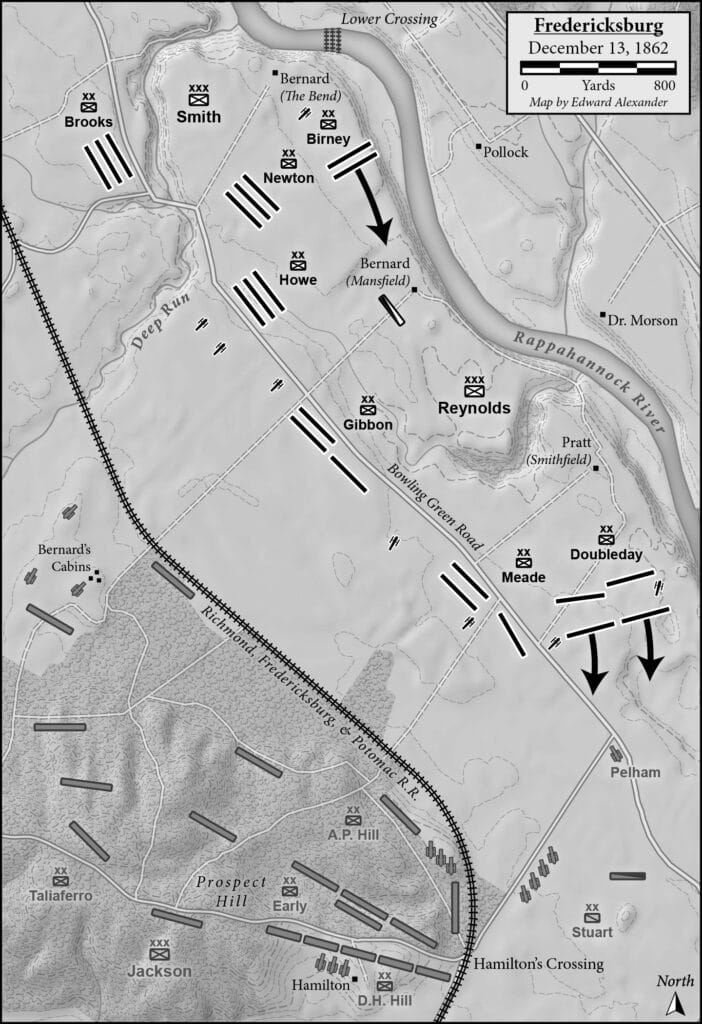

But who were Pelham and his Confederate gunners actually fighting that morning? While the advanced artillery pieces drew fire from multiple Union batteries and probably even from some long-range guns across the river, two particular Federal batteries can be easily identified as Pelham’s opponents: the 1st New Hampshire Battery and Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery. Reading through the Official Records gives context and glimpses of the Union side of the story during the dramatic early shots in the morning of December 13.

Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, overseeing artillery for the Union I Corps, wrote on December 22, 1862, in his official report for the battle of Fredericksburg:

“Meanwhile the Third Division, under General Meade, had also changed front, and formed one brigade in line, with the Second Division on the left of the fence; Ransom’s battery was posted to the right of a small hut, and Cooper’s about 100 yards to the left of it, while Simpson took up a position to right angles with his left resting on the public road. The first two of these batteries replied to the enemy’s guns on the crest, and to a battery in the open field to their left, while Lieutenant Simpson engaged a section posted in the corner of the hedges, at the junction of the Bowling Green road and that to Captain Hamilton’s.This section was so well sheltered by the cedar trees and hedge that it was difficult to meet its fire effectually, until the advance of General Doubleday’s division….” (emphasis added for Pelham’s position and action)[i]

Commanding infantry, Gen. Abner Doubleday also mentioned the artillery moment in his official report, dated December 22, 1862. His division was on the move, maneuvering between the Rappahannock River and the Bowling Green Road, driving back some Confederate skirmishers and capturing a potential artillery position along the river. Then:

“Colonel Rogers, with the Third Brigade, changed front forward, advancing rapidly, and took possession of the Bowling Green road, driving back the enemy’s sharpshooters and silencing a battery not more than 500 or 600 yards in our front. Gerrish’s battery was now placed to the right and rear of Rogers’ position, near the intersection of a cross-road with the Bowling Green road. Colonel Rogers supported the guns in rear, leaving two companies in the road to protect the cannoneers from the rebel skirmishers.”[ii](emphasis added; this is almost certainly when advancing infantry threatened Pelham and forced him back. Confederate accounts say Pelham ran out of ammunition. Most likely, it was a combination of low ammunition and advancing Union troops.)

Lieutenant Frederick M. Edgell of the 1st New Hampshire Light Battery penned his official report on December 18, 1862. This battery had crossed the Rappahannock River, using the pontoon bridge Lower Crossing, during the afternoon of December 12. As the cannoneers positioned their guns and awaited orders, they may have remembered their previous battles of that year at Second Manassas and Antietam.

“…when we were ordered, with Battery B, Fourth Artillery, to move down to the left. After advancing about a mile, we opened fire, with shell, upon a body of cavalry in a wood near the river, and in the turnpike to the right. This drove them from the position with some loss. We immediately occupied the ground, and, turning to the right, advanced to the turnpike, our battering being on the extreme left. The enemy now opened upon us with shell from the heights in the front and to the left, distance about 1,100 yards.” (emphasis added; this is almost certainly a description of the First New Hampshire’s tangle with Pelham.)

After Pelham’s departure, the 1st New Hampshire’s cannons drew enemy artillery fire from Confederate guns along Prospect Hill and possibly other positions along the Confederate right flank. Lieutenant Edgell reported the effects:

“We had now 3 men killed; our captain and 10 men wounded; a wheel and pole smashed, and our limber-chests nearly empty. I now ordered the pieces to retire to where our caissons were stationed, refitted and filled the chests, and immediately returned to our position, and continued firing occasionally, in reply to the enemy, till dark, when the battery was ordered to move a little farther to the right, and in this position remained till morning…. The officers and men of the battery behaved with their usual good courage, although the fighting was more destructive to them than on any former occasion.”[iii]

Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery took a notable part in confronting Pelham. Part of the Regular U.S. Army, this battery had been assigned to the I Corps of the Army of the Potomac since April 1862 and had already seen action at Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, and Antietam.

Second Lieutenant James Stewart wrote his official report sometime in the later half of December 1862:

“I was then ordered by the general to go to the assistance of Captain Gerrish’s battery, Colonel Wainwright directing me to go on the right of that battery, which at that time was under fire from two batteries on our extreme left. I immediately came in battery, and, after firing several rounds from each gun, succeeded in silencing the enemy’s fire, blowing up one of their caissons, and driving them off. During this time, another battery of the enemy on our left opened an enfilading fire. I immediately changed position and engaged it, and after firing some twenty minutes drove him off, disabling one of his guns and blowing up a caisson, and preventing him from carrying his disabled gun off during three successive attempts, although well supported by his sharpshooters, who were very destructive to my men and horses. In this position I had 2 men killed and 6 wounded, besides a loss of 8 horses killed; 4 wounded so severely as to be abandoned; 1 slightly wounded, and 2 sets of wheel and 4 sets of lead harness being so cut up by the fragments of shell as to be utterly unserviceable. During the latter part of the engagement my battery was supported by the Fourteenth Brooklyn.” (emphasis added)[iv]

This description matches some details from the Confederate side, that one cannon was disabled as it tried to reach Pelham’s position. It is interesting that Lt. Stewart thought there were two Confederate batteries since other details from both Union and Confederate accounts align to this probably being a description of firing on Pelham. Perhaps the Confederates left out some details? Or likely the rate of fire and changing positions from the advanced pieces seemed like there were more cannons than two?

Colonel William F. Rodgers of the 21st New York Infantry noted in his report dated December 19:

“Passing these woods, the enemy’s artillery and skirmishers, posted on the right of the Bowling Green road, commenced a rapid fire upon us, when, changing front forward on the first company of the first line, the brigade advanced rapidly and took possession of the Bowling Green road, driving back the enemy’s skirmishers and silencing a battery planted not more than 500 or 600 yards in our front. (emphasis added)”[v]

A few details stand out from these reports’ excerpts.

- All these Union reports were written within days of the battle, making them about as reliable as official reports can be.

- Union artillerymen and infantry consistently thought Pelham had more cannon in the advanced position along the Bowling Green Road. This has been traditionally—and probably best—interpreted as the rapid Confederate fire and moving position slightly between shots.

- The description of Pelham’s location is relatively consistent: along the Bowling Green Road in a copse of trees somewhere in the vicinity of an intersecting lane that led toward the Hamilton’s Crossing.

- The 1st New Hampshire report gives a sense of the destruction suffered by Pelham’s detachment. One cannon lost—probably the support trying to reach Pelham and that was also noted destroyed in Confederate accounts. And then a glimpse of casualties and a caisson.

- The reports consistently mention Confederate skirmishers, and some Union officers thought there was either enemy cavalry in the area or they mistook Pelham’s small group for cavalry. Either way, Pelham still had an advanced position and lacked the protection of Confederate infantry.

- The Union reports also corroborate that a combined infantry and artillery effort drove Pelham out of the copse of trees.

- (The reports also point to more Union artillery shots fired as Doubleday’s troops cleared out Confederate skirmishers closer to the river and detailed more of the artillery fight that erupted later in the morning and afternoon. But that will have to wait for another blog post or book.)

While John Pelham grabs the spotlight in traditional narratives in the early part of the battle at the southeast side of the Fredericksburg lines, it is worthwhile to see what his artillery opponents wrote. To the Union artillerymen that day, Pelham was just “a battery 500 or 600 yards to our front.” Though he became “Gallant Pelham” in those moments, according to General Robert E. Lee, the perspective shifts as Union artillerymen gave their reports of a just few more cannons to silence. There are two sides to every story, and Pelham’s opponents were not nameless, silent antagonists.

Read more in one of the newest books in the Emerging Civil War Series—Glorious Courage: John Pelham in the Civil War by Sarah Kay Bierle (May 2025).

Sources:

[i] Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Volume 21: Wainwright, Official Report, pages 458.

[ii] Ibid., Doubleday, Official Report, pages 461-462.

[iii] Ibid., Edgell, 1st New Hampshire Light Battery, Official Report, pages 465-466.

[iv] Ibid., Stewart, Battery B of 4th US Artillery, Official Report, pages 468-469.

[v] Ibid., Rodgers, 21st New York Infantry, Official Report, pages 473-474.

Thanks for this detailed description of Pelham’s artillery fight.

Excellent, new perspectives. Thanks

I know Pelhan was at the intersection of the Bowling Green & Hamilton’s Crossing Road from about 10 until 11 in the morning on Dec. 17. Stewart’s Light Company B was not engaged against Pelham at that time.