Repugnant to Humanity: John Singleton Mosby and the Legal and Moral Challenges of Irregular Warfare

ECW welcomes back guest author Collin Hayward.

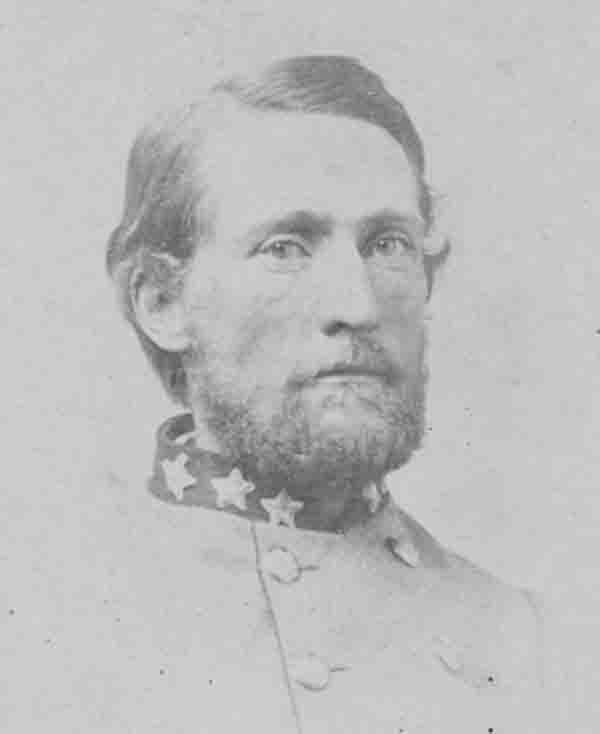

Colonel John Singleton Mosby was a lawyer before the war, but he quickly demonstrated his abilities as an excellent cavalryman, first as a scout and then as an officer on Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s staff early in the war.[1] Despite misgivings from some senior Confederate leaders about irregular warfare, Stuart gained approval from Gen. Robert E. Lee for Mosby to form a unit of irregular cavalry, called “Partisan Rangers.”[2]

For the duration of the war, Mosby’s Partisan Rangers bedeviled Union forces in Northern Virginia so severely that the region from the entrance to the Shenandoah Valley to the southern approaches to Washington was nicknamed “Mosby’s Confederacy” for his ability to raid and harass these areas of nominal Union control.[3] By the time of the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Mosby was a polarizing figure whom Southerners regarded as a daring hero and Northerners regarded as little more than a bandit.[4]

When Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan initiated his campaign to devastate the Valley, Mosby primarily focused on raiding Sheridan’s supply lines.[5] The legal status of partisan rangers was contentious. During this campaign Union authorities stated that they would execute Mosby’s men if they were captured. The Confederate government protested, arguing that they were legitimate combatants and observing that Mosby’s men had treated captured Union soldiers in accordance with the customs of war. On September 22, 1864, Union troops executed six of Mosby’s Rangers and a local civilian boy they suspected of working with the Rangers near Front Royal, Virginia.[6]

Mosby formulated a legal argument for reprisals and gained concurrence from his commanders and the Confederate war department.[7] Throughout the war, Mosby’s troops had captured hundreds of Union prisoners, but following the execution of his men and the approval of his plan, he ordered a large group of prisoners to draw lots and sentenced to death the seven men who had drawn short straws.

After executing five of the seven men, Mosby sent a letter to Sheridan in which he stated that he had retaliated only against men of the command that he believed had carried out the executions of his own men. He wrote that “hereafter, prisoners falling into my hands will be treated with kindness due to their condition, unless some new barbarity shall compel me, reluctantly, to adopt a line of policy repugnant to humanity.”[8]

Although no copy of Sheridan’s reply exists, the execution of prisoners ceased.[9] Mosby continued leading his Rangers through the end of the war. Though he never formally surrendered, he disbanded his unit and eventually turned himself in and accepted parole. He went on to practice law after the war, serve in state government, and eventually serve as the American consul to Hong Kong.[10]

Analysis

Despite lack of any pre-war military training, Mosby forced the Union to dedicate significant combat power away from their front lines to guard rear areas. Mosby recognized that small groups of determined horsemen who knew the terrain and communities of Union-occupied areas could harass the federal army’s extensive supply lines. Mosby clearly recognized that for irregular forces to be successful, they must understand the operational environment.[11] He demonstrated this through his ability to operate with seeming impunity in Union rear areas by relying on the local populace for resources, intelligence, guides, and recruits. Mosby’s popular support throughout his so-called Confederacy embodies Mao Zedong’s later dictum that a guerrilla must be able to move through the people as a fish moves through water.[12]

Mosby faced a challenge common to practitioners of irregular warfare, namely having his soldiers treated as criminals rather than legal combatants. Mosby’s background before and during the war led him to frame the issue as a fundamentally legal matter,[13] which allowed him to demonstrate both restraint and unnecessary escalation. In addition to his pre-war experience as a lawyer, Mosby’s wartime experience was characterized by both armies generally abiding by the norms and laws of war, so he viewed the execution of his men as an aberration and looked for a means to halt the escalation and return to the previous accepted practices of warfare, rather than provoking further escalation through retaliatory violence as occurred in other theaters of the war.[14]

Mosby is a complex case. The execution of prisoners of war today is a breach of the Law of Armed Conflict’s “right to life” clause, a law that did not exist at the time of the Civil War.[15] Mosby’s actions are rightfully controversial, but his thought process clearly demonstrated a need to de-escalate a situation he saw as likely to result in increasingly unethical behavior. His stated intent to revert to a policy of humane treatment and his insistence on a legal review for his proposed course of action demonstrate his intent to maintain an ethically aligned organization.[16] Mosby successfully walked a very fine tightrope; if he did not respond to the hanging of his men, then he lent credibility to the claim that his men were not legal combatants, but if he responded too violently he risked further delegitimizing his formation.

Mosby’s ultimate success in maintaining his organization’s legitimacy is demonstrated by the paroles his men received. After initially being expressly excluded from the favorable treatment afforded to the rest of Lee’s army after the surrender at Appomattox, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant directly interceded and offered Mosby’s men the same parole as he had offered the rest of Lee’s army.[17] This stands in stark contrast to other irregular Confederate formations. After a war characterized by a cycle of retaliatory violence that saw non-combatants frequently targeted by both sides, many Confederate “bushwhacker” groups like Quantrill’s Raiders were specifically excluded from the terms of surrender and parole offered to conventional Confederate units[18]. Given Mosby’s original exclusion from the terms extended to the Army of Northern Virginia, it is not difficult to imagine how different the fate of Mosby and his men might have been had he not established a precedent of respect for the laws of war.

Collin Hayward is an Army Officer and qualified Army Historian specializing in the study of irregular warfare. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Virginia Tech and Masters degrees from American University and the Army Command and Staff College, where he was an Art of War Scholar. He has previously published an analysis of historical case studies in the InterAgency Journal titled “How to Win Without Fighting: Cold War Lessons on the Risks and Rewards of Political Warfare in Strategic Competition”.

Endnotes:

[1] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 737.

[2] Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants: Cedar Mountain to Chancellorsville, vol. 2, 3 vols. (New York, NY: Charles Scribners Sons, 1971), 455.

[3] McPherson, 738.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants: Gettysburg to Appomattox, vol. 3, 3 vols. (New York, NY: Charles Scribners Sons, 1972), 576.

[6] Rob Orrison, “‘Mosby Will Hang Ten of You for Every One of Us!’ The Black Flag in the Shenandoah Valley,” Emerging Civil War, accessed May 14, 2024, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2014/09/24/mosby-will-hang-ten-of-you-for-every-one-of-us-the-black-flag-in-the-shenandoah-valley/.

[7] Rob Orrison, “‘I Regret That Fate Thrust Such a Duty upon Me…’ Mosby, Custer and the Black Flag in the Shenandoah Valley Part II,” Emerging Civil War, accessed May 14, 2024, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2014/11/07/i-regret-that-fate-thrust-such-a-duty-upon-me-mosby-custer-and-the-black-flag-in-the-shenandoah-valley-part-ii/.

[8] John Singleton Mosby, Gray Ghost: The Memoirs of Colonel John S. Mosby, Eyewitness to the Civil War (New York, NY: Bantam, 1992), 237.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Mosby, 311.

[11] “SOF Imperatives,” SOF Imperatives Page, n.d., accessed May 17, 2024, https://www.soc.mil/USASOCHQ/SOFImperatives.html.

[12] Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, FMFRP 12-18 Mao Tse-tung on Guerrilla Warfare (Washington, DC: US Marine Corps, 1989), 93.

[13] Mosby, 237.

[14] Collin Hayward, “Foul, Brutal, Savage, and Damnable: Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence and the Pitfalls of Reciprocal Violence,” Emerging Civil War, July 8, 2025, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2025/07/08/foul-brutal-savage-and-damnable-quantrills-raid-on-lawrence-and-the-pitfalls-of-reciprocal-violence/.

[15] “The Law of Armed Conflict,” International Committee of the Red Cross, accessed May 17, 2024, https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/law1_final.pdf.

[16] Mosby, 288-289.

[17] Mosby, 305.

[18] Hayward, “Foul, Brutal, Savage, and Damnable.”

Home guard militia John Read, an abolitionist taken prisoner in Falls Church by Mosby’s men during a Confederate raid, was subsequently found shot in the back of the head near Hunter’s Mill, about 15 miles away, the day after his capture.

I was always under the impression that “McNeill’s Rangers” formed and led originally by John Hanse McNeill, was accorded the same status as Mosby’s Rangers. McNeill’s Rangers home base was near Moorefield, in Hardy County, WV. Most of their actions were in the South Branch Valley, but they also raided north into the line of the B&O Railroad and also occasionally into the Shenandoah Valley. Their most famous exploit was slipping into Cumberland, Maryland and capturing Generals Crook and Kelly on February 21, 1865.

I’m currently reading “Grey Ghosts and Rebel Raiders” as a refresher from half a lifetime ago. Virgil Carrington Jones devotes a full chapter to the issues related to irregular warfare. “International Law Clears Guerrillas,” the title of Chapter 10, outlines the issues related to the Confederate Rangers, and seems to settle the controversy regarding their treatment early on in the war. As the war progressed, several Union Generals (Pope, Milroy, & Sheridan to name several) seemed to ignore the earlier understandings, probably as a result of their frustrations related to quell the continuation of partisan attacks.

I’ll encourage all to read “Grey Ghosts and Rebel Raiders.” It’s full of expanded versions of the partisan actions throughout the war, accentuated by the literary craftsmanship of a true storyteller.

My father served as a Navy Corpsman in the Korean War – five decorations – with a man from Front Royal, whose great-grandfather was an officer in the Army of Northern Virginia. We visited them on our camping trips in the Shenandoah Valley when I was a boy. They lived in Front Royal, and still do. They despised Sheridan and what he did in the Valley to innocent people – and still do.