Enough with the Lion and the Fox: John Bell Hood at Franklin

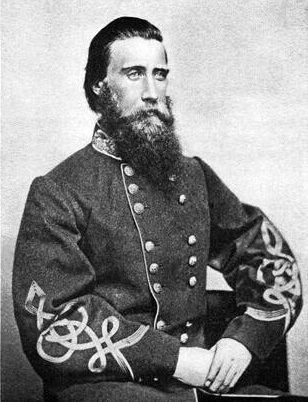

Just before 4:00 PM, on November 30, 1864, Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood decided to attack the U.S. Army’s defensive positions at Franklin, Tennessee. The horrific battle that ensued ultimately led to the demise of the Army of Tennessee and the destruction of the army’s command structure. What else could Hood have done? That question has been posed in various formats and has been the subject of numerous texts, scholarly journal articles, online entries, documentaries, tours, and Roundtable talks. Historians, guides, and armchair generals have questioned his aptitude, mental state, physical health, and even what role a failed romance may have played in the disastrous defeat (seriously, Wiley Sword?).[1]

Upon consideration of Hood’s entire career, however, the decision at Franklin is unsurprising. Hood’s reputation as a fighter was well-earned, and in many ways, his decision to attack at Franklin was made days, weeks, or even months in advance. Was Hood fated to order a frontal assault at Franklin? Or did the gods of war command him to do so? Probably not. I submit, however, that Hood’s decision was, if anything, inspired by his military experience and his time as a pupil under the Civil War’s most aggressive leader, Robert E. Lee. Hood’s appreciation for Lee’s mode of warfare inspired and informed his own command in 1864 and led to the decision at Franklin.

A student of Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Hood’s star rose in the victorious early days of the Army of Northern Virginia. Throughout 1862 and into 1863, Lee, with Jackson and James Longstreet, brought the war to the Army of the Potomac. In offensive campaigns against U.S. Army Gen. George B. McClellan, John Pope, Ambrose Burnside, and Joseph Hooker, Lee carried out an impressive array of victories. At the brigade and division command levels, Hood excelled and conducted himself exceedingly well in the art of offensive warfare. Twice wounded by the summer of 1864, the Confederate high command sent Hood to the Western Theater to lead a corps of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee.

His performance as a corps commander has garnered some scrutiny from scholars over the last century and a half, but, overall, he performed ably. His appointment to army command came in July 1864 as U.S. Army Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman maneuvered across the Chattahoochee River toward Atlanta. Hood inherited Johnston’s material situation and faced overwhelming odds against Sherman, but still held the line at Atlanta until September. As fires raged through half of Atlanta and the last of the Confederate soldiers evacuated, Hood moved his army south to Lovejoy’s Station and there set about planning future operations.

An often overlooked, but crucial point to consider is that by October 1864, Hood commanded the last, mobile, effective army in the Confederacy. As such, he planned for an offensive campaign into Tennessee to put his lethal force on the march and attempted to reverse the army’s late misfortunes.

On November 20, 1864, the last of Hood’s Army crossed the pontoons over the Tennessee River and marched into the Volunteer State, intent to capture Nashville. Hood’s offensive movement north drew Federal forces under the command of Maj. Gen. George Thomas to Nashville as well as a delaying force commanded by Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield. On November 24, Hood and Schofield collided at Columbia, and five days later, the Confederates attempted to outpace the U.S. Army to Spring Hill.

Early on November 29, Hood moved two-thirds of his army, less his artillery, across the Duck River to interpose his forces between Schofield and Nashville. Hood’s plan called for two corps of his army to march in Schofield’s rear and seize the Columbia Turnpike while the remaining portion of his army held the Federals to the south along the Duck River, and his cavalry corps drove a wedge between the U.S. Army’s mounted contingent and the main body. If Hood hoped to capture Nashville, this daring flank march was his best chance. The entire campaign rested on his army’s success or failure at Spring Hill.

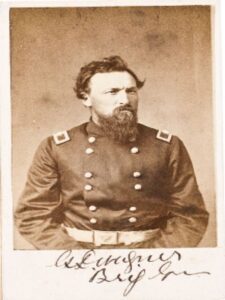

Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry drove back Schofield’s cavalry in the early morning hours. After Maj. Gen. James Wilson’s troopers fell back from Hurt’s Crossroads and retreated north, Forrest continued to screen Hood’s infantry’s advance as the last of Wilson’s troopers were pushed back toward Franklin. Aware that Hood’s forces were on the move, Schofield evacuated the reserve artillery and the army’s supply train. Short of cavalry, he ordered Maj. Gen. David Stanley to march with two divisions and escort the guns and wagons. At Rutherford Creek, Stanley dispatched half of his contingent to remain and guard the vital crossing while he continued north with Brig. Gen. George Wagner’s division.

Meanwhile, two corps of infantry led by Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham and Lt. Gen. A.P. Stewart snaked along the Davis Ford Road. By noon, Wagner’s division and Forrest’s cavalry squared off in Spring Hill. To the south, Hood and his flanking column pressed on and, just after 3:00 PM, Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s division, with John C. Brown and William Bate’s divisions in tow, attacked Wagner’s position. Cleburne’s men smashed through one brigade and, according to one of his brigade commanders, came within a twenty-minute march to the Columbia Turnpike.[2]

Darkness, a massive reconnaissance failure on the part of the rebel cavalry command, poor communication between Cheatham, Stewart, Forrest, and Hood, and, perhaps, most importantly, exhaustion, paralyzed the Confederate movement for the remainder of the night. As Hood’s men rested astride the Columbia Pike, Schofield and roughly 20,000 of his men marched past the twinkling campfires and north to Franklin.

By 6:00 AM, Hood learned of Schofield’s escape and issued orders to pursue the fleeing Federals. In Franklin, Schofield ordered Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox to construct defenses on the south side of town to protect the army as it escaped over the Harpeth River. By 2:30 PM, much of the Federal line was in position, and in the distance, skirmishing between the army’s advanced line, manned by two brigades of Wagner’s Division, and Hood’s skirmishers could be heard. For Hood, the greatest chance of success had slipped away at Spring Hill. Even as he surveyed the situation, Hood observed Schofield’s preparations to evacuate Franklin. The Federal army commander did not intend to stay and fight along Cox’s defensive line. Time was rapidly ticking away. If Hood were to succeed at all, he needed to strike a blow against Schofield before he crossed the Harpeth River and reached the safety of the Brentwood Hills and the outskirts of Nashville.

The ground south of Franklin stretched out along a rolling plain upon which the U.S. Army established three layers of defenses to include Wagner’s advanced line, the main line, which bristled with thirty-eight guns. Behind the hastily dug earthworks, Cox established a secondary line of works, which Hood likely could not see. Hood’s options were quickly disappearing before his eyes. Faced with a difficult choice, he could realistically only select one of these options:

1) Withdraw and abandon the objective of Nashville

-A retreat, especially after Spring Hill, would have very likely led to the dissolution of the Army of Tennessee.

2) Attempt to outflank Schofield across the Harpeth and fix his men between the Federals in Franklin and Nashville

-Not only would crossing the Harpeth prove difficult, but time and daylight would make such a maneuver unachievable. Additionally, to interpose his army with its rear to Nashville was a risk he could ill afford to take. Wilson’s cavalry had consolidated on the north side of the river, and Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s division crossed the Harpeth and assumed a defensive position on the north bank. If Hood were to attempt a crossing, these troops could have made quick work of turning back his best efforts.

3) Entrench the Army of Tennessee and attempt to hold Schofield in earthworks at Franklin

-This would not in any way advance Hood’s hopes to capture Nashville, nor would Schofield have remained in Franklin long enough to become committed to holding the line there. Even by 3:00 PM some of the army’s first guns and wagons rolled over the bridges north of town. Each minute Hood spent in contemplation gave Schofield another minute to evacuate.

4) Attack the Federal line

-Hood’s army had the potential to break the Federal line and, if that opening were exploited, deal a serious blow to Schofield. Though Hood advanced without the bulk of his army’s artillery (which you do not need in an offensive fight), he still wielded a force of 20,000 veteran infantrymen under experienced leadership.

“We shall make the fight,” Hood declared. In his memoir, Hood provided the best insight and assessment of his decision for a frontal assault:

“I hereupon decided, before the enemy would be able to reach his stronghold at Nashville, to make that same afternoon another and final effort to overtake and rout him, and drive him into the Big Harpeth river at Franklin, since I could no longer hope to get between him and Nashville, by reason of the short distance from Franklin to that city, and the advantage which the Federals enjoyed in the possession of the direct road.”[3]

Of course, with hindsight, Hood’s decision to attack proved fatal. Any amount of armchair generalship is useless. He was there, and we, the casual reader or academic, were not. Like it or not, Hood was the most qualified, capable commander left to lead the Army of Tennessee, and he did so until the defeats at Franklin and Nashville rendered the army ineffective. Do we judge the leadership of Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg with enough scrutiny? Is there a line of people willing to say that Lee’s decision to carry out Pickett’s Charge was entirely dictated by his poor health and ill-fitness for command? Where are the critics of Lee’s decision to charge at Malvern Hill, and why have they not asserted that Lee lacked the necessary mental aptitude to command an army? Will someone seriously say that Lee should have never been promoted above colonel because he was out of his depth at anything above the brigade level? Lee’s offensive tactical mindset was unshakable. Even when forced to take a defensive posture, Lee still fought on the offensive.

Had Hood’s charge worked, and it very nearly did had it not been for the crucial placement of artillery batteries central to the breakthrough and the strained effort of the secondary line, as well as Brig. Gen. James Reilly and Col. Emerson Opdycke’s countercharge, the loudest critics would be silent. But it did not work, and to this day, it is difficult to unravel the why and the how behind the decision-making process of the Confederate commander.

Why did Hood attack at Franklin?

W.W.L.D?

[1] James Lee McDonough and Thomas Connelly, Five Tragic Hours: The Battle of Franklin, (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1983), 15-18; Wiley Sword, Embrace an Angry Wind- The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville, (NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992), 25, 36, 155, 179-180.

[2] Daniel C. Govan quoted in Irving Buck, Cleburne and His Command, (Wilmington, NC, 1995), 273.

[3] John Bell Hood, Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies, (New Orleans, LA: Hood Orphan Memorial Fund, 1880), 291, 296; W.H. Rees, “Cleburne’s Men at Franklin.” The Confederate Veteran, (Nashville, TN: S.A. Cunningham, 1901), 54.

Hood lost at least 105 confirmed dead a half mile west of today’s Reno Monument at Fox’s Gap. Probably many more. Many of the Confederate dead claimed at Antietam died at Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps. A significant analysis of Hood will appear in my next book. One must thank Ezra Carman in part for elevating Hood in currently accepted and erroneous Civil War literature.

Preach!! To say that Hood had any option other than to attack or in effect “dissolve” his army is to ignore the facts as they were.

Maneuver was clearly the better option over frontal assaults every single time. Jackson fought when he needed to but knew the value of maneuver, especially in the Shenandoah. Hood was just not good at independent command.

I think we have a tendency to simplify complex military decisions to things like “stupidity” when in reality these decisions were made in the face of complex factors (weather, inaccurate or conflicting intelligence, etc.). I think you articulate that complexity really well!

Super article, thank you for this exceptional elucidation. Wasn’t the Harpeth high which forced Schofield to make a stand, where had he been able to cross it, unscathed escape would have been his. Forrest proposed that a flank attack, with infantry support, would bring success vs a frontal assault. But the infantry had been on the march for several days, there were few hours of daylight left for preparation and then execution, and there were other impractibilities to the respected cavalry general’s proposal.

Upon the subject of his reputation, Hood wrote, “Touching this same accusation of rashness, put forth by my opponents, I merely state that the confidence reposed in me upon so many occasions, and during a service of three years, by Generals Lee, Jackson, and Longstreet, in addition to the letters of these distinguished commanders, expressive of satisfaction with my course, is a sufficient refutation of the charge.” See his own words in, “Advance and Retreat,” completed by Hood shortly before his death at 48, killed by an epidemic, pg 312.

Tangentially off topic. Stonewall recommended Hood’s promotion to MG. Interesting aside – according to Hood after the war, at Fredericksburg Stonewall told him he didn’t expect to survive the war, and Hood told Stonewall that he expected to survive the war badly shattered. And as for becoming Lt General, it was Longstreet that recommended MG Hood for promotion to the rank of LG, endorsed by General Bragg.

Hood expressed, “Of all men living, not excepting our incomparable Lee himself, I would rather follow James Longstreet in a forlorn hope or desperate encounter against heavy odds. He was our hardest hitter.”

Beg to disagree. Patrick Cleburne and Bedford Forest, two very aggressive Confederate commanders, were against the attack arguing it would fail with significant loss of life. A suicidal charge is not a reasonable option except for those without hope. Thousands of men lost their lives and were maimed because of a rash decision. After learning Hood was taking command of the Army of Tennessee, W.T. Sherman told his wife in a July 29, 1864 letter that Hood “is reckless of the lives of his Men.” In his new two volumes on the battle of Gaines’s Mill, R.E.L. Krick praises Hood for his gallantry in leading his brigade in the battle, but added that Hood was elevated “beyond his capabilities” to the Army of Tennessee in 1864. (857)

As Pickett allegedly said when asked why “his” (not actually his, but Lee’s) charge had failed, “the Yankees had something to do with it.” In this case, it was Schofield’s wise decision to have Jacob Cox and not David Stanley set up his defenses against a possible frontal attack by Hood that had “something to do with it.” Cox knew what to do and did it well, including setting up that second line of defense in the center. It was Cox who “saved the day,” despite what any others might claim.

We must use caution when presenting critical analysis of a General’s action unless we have all the information. Lee’s attack on the third day at Gettysburg? Illness had nothing to do with it; we must remember that every report he’d received was that the Federals were strong on their wings and weak in the center, and the previous day, after Longstreet attacked more than five hours late, he had breached the Federal center; furthermore, he was assuming Longstreet would properly handle the pre-attack artillery bombardment – and he bungled it – and that Longstreet would have finished the bombardment and started his infantry on time: by 1:00 PM – and he didn’t even start firing until 1 PM. While true the attack should probably not have been launched, Lee’s real error was putting it in the hands of Longstreet, who lacked the skills to make it.

Lee’s attack at Malvern Hill? It occurred because Magruder could not comprehend his orders and launched the attack prematurely and hopelessly.

Hood’s attack at Franklin? Anyone who doubts Jefferson Davis ordered him to make the attack is fooling himself.

This was a great article … I enjoyed reading it.

The answer to your final question regarding why Hood attacked at Franklin, however, is simple … it was completely in character with Hood’s decision making … his performance defending Atlanta was a succession of mistimed, ill-conceived, and poorly executed attacks against Sherman — actions that often-included frontal assaults on entrenched Union positions … his leadership in Tennessee was more of the same.

I agree that “armchair generalship is useless” … and arguments that Hood came close at Franklin are similarly unsatisfying … even if he had prevailed, Franklin would have been a pyrrhic victory given his losses in men and general officers … what we do know with certainty, however, is Hood’s record between July and December 1864 – he was 0 – 7 … Hood was brave soldier but a complete disaster as an army commander.

Good article. In studying the Middle TN campaign, I am most impressed with Schofield’s excellent use of defensive tactics to delay Hood’s march toward Nashville. I would think his “delaying action” is still studied by military professionals today.