Apple TV’s Manhunt: Fact or Fiction

For over a year now, I’ve been eager to watch Apple TV’s mini-series Manhunt. After securing a subscription to the streaming service, I finally sat down to watch. Like many Civil War enthusiasts, I felt that a limited series on the dramatic, twelve-day manhunt to capture John Wilkes Booth had great promise. Manhunt chronicles that story, but it also addresses events of Reconstruction and civil rights. This format proves to be a useful teaching tool, but it also causes the series feel like it bites off more than it can chew.

The series also plays fast and loose with a number of conspiracy theories, some of which have long been dismissed by scholars and historians. Thus, this post highlights a few elements that the series gets right and some that it does not.

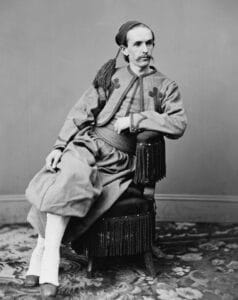

Did Edwin Stanton really have asthma?

Yes. Stanton had his first asthma attack when he was a child. His condition prevented him from participating in games and physical activities with the other boys of his hometown of Steubenville, Ohio, so Stanton spent much of his childhood reading books and poetry. Decades later, Stanton’s asthma prevented him from enlisting in the U.S. Army during the Mexican-American War. Its severity worsened with age, too. By 1868, Stanton’s asthma made it difficult for him to give long speeches, and his breathing grew more laborious.[1]

Did Catholic priests protect John Surratt during the manhunt?

Yes. Following the assassination, the Federal government worked hard to locate Surratt, whom they quickly identified as a key member of the conspiracy. Though some witnesses claimed to have seen him outside Ford’s Theatre on the night of April 14, Surratt later admitted he was in Elmira, New York. He began his escape to Canada the following day, April 15, after learning about Lincoln’s assassination. Following his arrival in Montreal, Surratt sought refuge from a Confederate agent, John Porterfield, who helped him cross the St. Lawrence River to the town of St. Liboire. There, Fr. Charles Boucher hid Surratt in the rectory of a local Catholic church.[2]

Manhunt erroneously depicts Stanton arriving in Canada to arrest Surratt just after the fugitive made his escape to Europe. In reality, the young conspirator remained in St. Liboire for his mother’s trial until August 1865. Surratt secured passage aboard the steamer Peruvian with the help of another Catholic priest, transporting him to the Confederate haven of Liverpool, England. From Liverpool, Surratt made his way to the Vatican where he enlisted as a papal Zouave.[3]

Surratt’s sanctuary among Catholics has sparked several conspiracy theories regarding the role of the Catholic church (or the pope) in orchestrating Lincoln’s assassination. Surprisingly, Manhunt does not deign to entertain any of these theories, but it accurately portrays Surratt’s refuge among fellow Catholics.

Did Secretary of War Stanton personally lead the manhunt for Booth?

No. By all accounts, Secretary of War Stanton remained behind in Washington during the twelve-day manhunt for Booth. Stanton played an active role in the investigation, personally interviewing witnesses and ordering a second performance of “Our American Cousin” in Ford’s Theatre for the purpose of reconstructing the crime scene. However, he did not personally pursue Booth across southern Maryland and Virginia alongside Union cavalry, nor did he personally track Suratt through New York and Canada with the help of Federal agents, both of which he does in the show.[4]

Was the Confederacy behind Lincoln’s assassination?

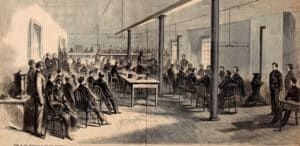

No, or at least it has never been proven. The “grand conspiracy” narrative portrayed in Manhunt was indeed pursued by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton during the conspirators’ trial, but it was ill advised.

Stanton was a shrewd lawyer, but he was a brazen politician. The ambitious secretary saw the conspiracy trial in the summer of 1865 as an opportunity to place a final nail in the coffin of Jefferson Davis and prosecute the Confederacy as a whole. While investigators found some evidence that linked Booth’s conspiracy to the greater Confederacy, prosecutors failed to convince the military tribunal of any credible connection between the conspirators and Jefferson Davis’s rebel government.[5] The evidence of a grand conspiracy has failed to hold up against posterity’s judgement, as well.

Manhunt’s portrayal of the trial suggests credibility to the grand conspiracy where there is none. While Stanton did not attend the court proceedings as he does in the series, he ruled over the trial with an iron fist. The secretary assembled a group of Union officers partial to his political machinations and refused to issue attendance passes to anyone but government or military officials, effectively hiding the trial from the public eye.[6]

The series shows that the charge of grand conspiracy between Booth’s cabal and the Confederacy fails only when a key witness—Sandford Conover—commits perjury by giving contradictory evidence. Conover, who is presented in the show as a double agent, claims to have witnessed Booth and Surratt planning the assassination alongside known Confederate agents. The defense dismantles his testimony by revealing that Conover simply “got the month wrong” when he witnessed Booth’s clandestine activity.

In reality, Conover’s perjury was much more significant, as he lied about his alias, James Wallace, during his initial testimony. In the show, the military tribunal admits that the grand conspiracy indictment has merit, but it fails to find the defendants guilty of conspiring with the Confederate government “due to tainted evidence and technicalities.” However, evidence of that connection was much more fragile, and Conover’s testimony demonstrates the War Department’s willingness to use tainted evidence to prosecute not only Booth’s conspirators but the Confederacy itself.

Were Edwin Stanton and Lincoln’s seamstress Elizabeth Keckley close friends?

No, Stanton and Keckley did not have the close friendship as portrayed in Manhunt, or at least no evidence suggests they did. Stanton was, however, a proponent of civil rights and Reconstruction, as demonstrated in the series by his support of Keckley’s autobiography, the proceeds of which funded the Freedmen’s Bureau. Stanton’s biographers debate what degree he believed in equality between whites and African Americans, but his support of the Radical Republican platform grew stronger during his tenure as secretary of war. Keckley and Stanton probably rubbed elbows in Washington social circles, but their interactions are not documented. Their fictional relationship in Manhunt is thus a vehicle to convey a larger story about Stanton’s support of racial equality.

Did Andrew Johnson want to let Booth escape without hunting him down?

No. Glenn Morshower gives an excellent portrayal of Vice President Andrew Johnson. However, the series depicts him immediately subverting Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction. Despite Stanton’s insistence, Johnson remains ambivalent about, if not opposed to, tracking down Booth. While the real President Johnson did eventually defy his administration’s plan for Reconstruction by granting amnesty to prominent former Confederates, this did not happen for another three years after Lincoln’s assassination. Immediately after taking the oath of office, Johnson vowed to get revenge on Lincoln’s killer and punish the Confederacy for its crimes. His rhetoric was so fiery that some Radical Republicans, including Sen. Benjamin Wade, briefly thought Johnson might be better suited to presiding over Reconstruction than Lincoln had.[7] The new president also approved of Stanton’s decision to try the conspirators before a military tribunal rather than within a civil court, which was seen by some members of the public as draconian. Johnson had the authority to pardon each of the conspirators but refused to do so—even Mary Surratt, whose precise connection to the plot proved rather tenuous.[8]

***

Overall, the series is entertaining, if a bit melodramatic at times. Anthony Boyle’s performance as John Wilkes Booth is standout, as is Lovie Simone’s performance as Mary Simms. Tobias Menzies provides a compelling interpretation of Edwin Stanton, even if his character deviates from the historical record at times. Manhunt is an engaging watch for any history buff and provides a great introduction for one of the most dramatic epochs in American history: the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Notes:

[1] Walter Stahr, Stanton: Lincoln’s War Secretary (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 10-15.

[2] Edward Steers, Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press), 231.

[3] Steers, Blood on the Moon, 231.

[5] Marvel, Lincoln’s Autocrat, 369.

[6] Marvel, Lincoln’s Autocrat, 377.

[7] Marvel, Lincoln’s Autocrat, 371, 376.

[8] Steers, Blood on the Moon, 211; Marvel, Lincoln’ s Autocrat, 372.

Where’s Stanton’s beard?

I have to agree with you on the beard. I was about 2/3 through the first episode before I realized that Menzies’s character was Stanton himself. I was waiting for someone with a giant beard to enter the room. I thought Menzies was Stanton’s fictitious strongman who would lead the investigation, then eventually realized the cut the beard off and kept him as Stanton.

Agreed. I knew Menzies was playing Stanton going in, but I wish they had attempted to make him resemble his historical appearance a bit more. I think if you can get past the lack of beard, his performance is really good!

Thank you for concisely answering many questions related to the history versus the Hollywood production. Your efforts will help answer those viewers whose only knowledge is the TV show.

You’re welcome!

i wasn’t aware of this series … thanks for letting us know and for this great review as well!

Evan, excellent (and useful) article, thank you.

Further on Surratt’s Catholic connection, Surratt had been a seminarian for a period.

The U.S. government discovered Surratt serving in the Papal Zouaves when a fellow Zouave, Henri Beaumont de Sainte-Marie, contacted U.S. Minister to Rome Rufus King in April 1866. Sainte-Marie had known Surratt in the U.S. and recognized him. Sainte-Marie confronted Surratt (who was using the name John Watson) who admitted his identity. According to Sainte-Marie, Surratt not only admitted his role in the plot to kill Lincoln, but claimed that he acted under orders of persons directly under Jefferson Davis. Surratt was arrested by Papal authorities, but escaped, only to be captured later. Sainte-Marie’s claim for the previously-offered $25,000 reward led to a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Shuey, Executor, v. United States, 92 U.S. 73 (1875). His claim was denied.

Kevin, thank you for the praise. Yes! I wanted to include more about Surratt’s fate and his time in the Papal Zouaves, but alas… Thanks for including it here! Maybe that could make a good future ECW post!

Evan, your post suggestion is a good idea. I may well take it up, as I am in the middle of preparing a talk to my Round Table (Roanoke, VA) on the diplomatic relationships of the Vatican with the CSA and the USA. I am deep within Rufus King’s dispatches to Seward, which include discussions of apprehending Surratt.