Book Review: The Battle of Gaines’s Mill, Volume 1: To the Banks of the Chickahominy & The Battle of Gaines’s Mill, Volume 2: Race Against the Setting Sun

![]()

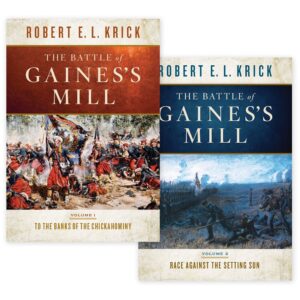

The Battle of Gaines’s Mill, Volume 1: To the Banks of the Chickahominy. By Robert E.L. Krick. Washington, D.C.: The American Battlefield Trust, 2025. Hardcover, 455 pp. $29.95

The Battle of Gaines’s Mill, Volume 1: To the Banks of the Chickahominy. By Robert E.L. Krick. Washington, D.C.: The American Battlefield Trust, 2025. Hardcover, 455 pp. $29.95

The Battle of Gaines’s Mill, Volume 2: Race Against the Setting Sun. By Robert E.L. Krick. Washington, D.C.: The American Battlefield Trust, 2025. Hardcover, 492 pp. $29.95

Reviewed by John B. Sinclair

Rumors have swirled for years around the Civil War community as to whether Robert E. L. Krick was toiling on a book on the battle of Gaines’s Mill. Though addressed in other books, it still lacked a comprehensive treatment. Krick spent thirty-three years as a historian on the staff of the Richmond National Battlefield, which includes the Gaines’s Mill battlefield. It is difficult to identify a historian better suited to the task. And Krick delivers.

The result is a two-volume work published by the American Battlefield Trust. The books total 947 pages and are of sturdy construction. The first volume fills 455 pages including an order of battle, with the bibliography and index deferred to the second volume. End notes follow each chapter. Photographs and illustrations, many from Krick’s personal collection, complement the narrative. While the 38 maps are good, they do not have certain terrain features some readers might want. A few battlefield-wide maps showing overall troop positions at certain points of the battle might have been helpful for geographically challenged readers.[1]

The bibliography reveals just how thorough and deep Krick’s years of research have been. Yet, unlike some authors who seemingly empty their research files into and clog their narratives, Krick is judicious in his selections, from command decisions to combat descriptions to soldier vignettes. He does a remarkable job in parsing through conflicting, scant, non-existent, muddled, self-serving, or score-settling accounts to provide readers with an objective and clear picture of how the battle unfolded.

Krick notes the difficulty of organizing his narrative without “hard margins” given the “multiple knots of heavy combat” occurring at the same time. (624) He deftly unties those knots, however, presenting a reasoned and coherent narrative. Throughout both volumes, Krick also offers readers a cornucopia of interesting sidebars on various aspects of Civil War combat.

Volume 1

Krick immediately places readers into the situation facing Robert E. Lee on the evening of June 26, 1862 after the battle of Mechanicsville. Lee decides to strike across the Chickahominy River to destroy the V Corps of the Army of Potomac (“AOP”) located on the north side of the river apart from the rest of George B. McClellan’s army. Lee hoped that Stonewall Jackson’s army arriving from the Shenandoah Valley could get behind the Federal position and act as an anvil against the hammer of A.P. Hill’s and James Longstreet’s commands attacking from the west. Astonishingly, despite the proximity of this battlefield to Richmond, Lee found a serious lack of reliable maps of the area. Combined with uncertainty as to the exact position of the V Corps line, Lee and his high command were initially delayed in launching their attacks during this battle, which Krick estimates lasted from approximately 2:30 p.m. until darkness descended at 8:00 p.m.[2]

McClellan had already decided before the battle to move the AOP back to the James River. Krick is withering in his criticism of McClellan’s prevarication and dissembling before and after this battle.

McClellan ordered Fitz John Porter’s V Corps back to the Gaines’s Mill area to slow the Confederate advance. The position selected was close to Union-held bridges over the Chickahominy. The corps deployed in a semi-arc behind Boatswain Creek, with the Federals’ western flank near the Chickahominy, a swampy river.

Porter began the battle with 27,000 men. He was later reinforced with Henry Slocum’s division of 7,000 soldiers. Combined with the arrival of Jackson’s Army of the Valley, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) had roughly 50,000-55,000 men at the Gaines’s Mill battlefield, an area of some 1,500 acres. At their zenith, the Union line was 1½ miles long while the Confederate line extended two miles.

Some historians have criticized Stonewall Jackson for arriving late from the Shenandoah for the battle. Krick effectively explains that while Jackson took a circuitous route due to poor guides and his habitual secrecy regarding his plans, his delayed arrival at Old Cold Harbor did not harm the ANV. Jackson ultimately arrived north of the right flank of the V Corps; Lee assigned D.H. Hill’s division to him for the course of the battle.

The initial substantial fighting in the western and central parts of the battlefield occurred in adjacent fields known as the Parsons and McGhee fields. These fields were separated by a 75-acre peninsula of “extremely thick woods” and “rough terrain.” (211) Krick labels these woods as “Griffin’s Woods” after Union Brig. Charles Griffin whose brigade was heavily engaged there. A belt of woods intersected this peninsula and extended across these fields from the Confederate side. In launching various attacks in these areas, A.P. Hill was unable to maintain tactical control over his men due to poor sight lines and other circumstances.[3] Hill’s attacks in Parson’s field were repulsed by the 3,000-man brigade of Brig. Gen. John Martindale, who had astutely ordered his men into two lines of defenses above Boatswain’s Creek behind log barricades, a precursor to later use of breastworks in the war.

In McGhee’s field, among the highlights was the famous charge of the 5th New York Zouaves to drive back the Confederates, resulting in substantial casualties to the Zouaves.[4] Repeated attacks left the field in a stalemate. The five-hour fight in Griffin’s Woods was a proverbial meat grinder with poor visibility and back-and-forth control that left brigades on both sides “shattered and torn.” (211) As Krick observes, “Rarely did any force recognize exactly where it was, or what role it was performing in the larger picture.” (318)

Although the ANV had substantial artillery present, its guns were mostly smoothbores. They were no match for the rifled pieces of Union artillery, on elevated ground, whose long-range guns tormented Confederate gun crews as well as Confederate infantry. Moreover, given open lines of sight for part of the battlefield, Union artillery on the other of the Chickahominy was able to enfilade Confederates operating against V Corps. While Union artillery was vastly superior to its Confederate counterpart, in the end it was not enough.

D.H. Hill’s division was initially in a westward-facing position due to poor intelligence regarding the eastern flank of the V Corps. Jackson ordered Hill to conduct a wheel swing of his division into the Union position at McGhee’s farm. Krick believes Hill failed to exercise proper control and coordination over this movement, which has caused historian confusion “to this day.”[5] (338) While the large 850-man 20th N.C. was able to punch a 300-yard opening in the Union line, there was no follow-up from other Confederate units to support the opening before it was temporarily closed by the VI Corps brigade led by Col. Joseph Bartlett.

Volume 1 ends with the dramatic breakthrough of the strong Union lines of Martindale’s brigade by Brig. Gen. Charles Whiting’s two brigade division. John Bell Hood took the lead by personally leading the 4th Texas. Krick tells the story in a compelling narrative. Using his powerful voice to inspire his men, Hood established his mark in the annals of the ANV with a 550-yard charge in the face of the strong Union lines that had repulsed earlier Confederate charges. Krick explains how despite the Federal 2-1 manpower advantage, good Confederate tactics, inspired leadership by Hood, and self-discipline propelled the Texans through artillery and infantry fire over Boatswain Creek. Martindale’s brigade gave way under the weight of the charge, with adjacent Union regiments gradually falling away as well.

Lee then ordered “an all-out attack” across the entire Confederate line, involving roughly 50,000 men. (437) Only one hour of daylight remained.

Volume 2

Under fire from Union artillery in front and from across the Chickahominy, Longstreet launched his attack against the western flank of the V Corps in the area occupied by Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield’s brigade. This attack occurred just after the breach of Martindale’s line. As Krick describes it, “The Union flank did not disintegrate all at once, nor did it follow any particular pattern.” (531) Butterfield was forced to withdraw his men as they were being cut off from the rest of the V Corps.[6]

Krick considers Brig. Gen. Charles Winder one of the Confederate heroes of the battle. On his own initiative, Winder became the de facto leader of the Confederate left flank. He cobbled together various disorganized and dispirited men along with his own Stonewall Brigade to form about nine regiments to charge the Union line. As Krick eloquently puts it, “Here was Charles Winder’s moment, and he seized it with gusto.” (644) Charging at twilight, Winder’s attack overwhelmed Bartlett’s Brigade and other Union forces at the McGhee house, a feat that Krick described as “one of the most impressive tactical accomplishments” at the battle. (725)

The battle for the Adams house ridge with its 16 Union cannon was another key moment in the closing parts of the battle. The artillerists, over whom no senior officer exercised control, encountered a moral dilemma. Although they enjoyed an excellent range of fire in front of them, the field in front of them was full of thousands of fleeing Federal soldiers with Confederates in close pursuit. Panic had set in. Nearly 25,000 Federals were in full retreat.

The capture of this ridge was preceded by a surprising Federal cavalry charge ordered by Brig. Gen. Philip St. George Cooke whom Porter had ordered to protect the Federal guns. Cooke sent 230 cavalrymen into the charging Confederates. The gallant, if foolhardy, charge was quickly repulsed. The resulting controversy over the charge continued for decades.

As darkness enveloped the battlefield, many thousands of fleeing Federals headed mostly for the Woodbury-Alexander bridge, creating a logjam. Elsewhere on the battlefield combat was petering out as the ANV gained control of the battlefield and friendly fire incidents lowered eagerness for firing.

In a belated response to Porter’s pleas to McClellan for help, two brigades, one led by Brig. Gen William French, and the Irish Brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Francis Meagher arrived at the bridge near the close of combat. They were met by Porter who ordered them forward to protect the Federal rear. The newcomers muscled their way across the bridge and restored some order and renewed spirit in the dispirited battle survivors. Taking their place on a nearby ridge, the French and Meagher brigades encountered little conflict with Confederates, who had largely stopped their advance due to the inky blackness of the night. Krick disassembles the post-battle myth that converted the Irish Brigade into the saviors of the V Corps and the AOP, a myth that is still perpetuated by some modern historians.[7]

McClellan spent the battle at his headquarters south of Chickahominy. From there he issued his infamous communique to Secretary of War Stanton blaming the Lincoln administration for his defeat. Krick explores McClellan’s mendacity regarding the battle’s outcome. The AOP was now in retreat to the James River.

Krick gives mixed marks to Lee’s performance, whom he credits for being active at the New Cold Harbor crossroads. The ANV’s attacks began too late in the day to achieve a more complete victory. Due to the lack of maps and firm intelligence, Lee never achieved a complete understanding of the battlefield, as woods and terrain screened the Federal’s troop and artillery positions. Nevertheless, Krick credits Lee for being aggressive and relying on his senior commanders, resulting in a morale-boosting victory that changed the momentum of the war. Though Krick finds Porter performed well under difficult circumstances, he castigates Porter for scapegoating Cooke for the defeat.

Gaines’s Mill was the largest battle of the Seven Days Campaign and largest battle fought around Richmond during the Civil War. Roughly 90,000 men were involved in the battle. Total killed and wounded amounted to roughly 12,000. Porter’s losses of some 6,700 included 2,700 Federals taken prisoner while Lee’s losses approached 7,500.

Krick’s narrative is sure-footed, eminently readable, easily digestible, and leavened by the dry humor for which he and his father are known. I found nary a spelling mistake, missing word, or grammatical error in the narrative. Krick’s Acknowledgments credits the initial editing work by his father, Robert K. Krick.[8]

The battle of Gaines’s Mill has found its comprehensive historian in Robert E.L. Krick. This work takes its place in the upper echelon of classic Civil War battle studies. Above all, it is a crackerjack read.

————

John B. Sinclair is a retired charitable foundation president and a retired attorney. He is a member of the Baltimore Civil War Roundtable, a member of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (James A. Garfield Camp No. 1), and a Life Member of the Lincoln Forum.

[1] There is a very helpful battlefield-wide map near the beginning of Volume 1 reflecting farms, taverns, and other structures and features, but with no troop placements. Moreover, most subtitles of each chapter helpfully indicate the western, central or eastern section of the battlefield being covered in that chapter.

[2] Lee spent most of the battle at the New Cold Harbor crossroads where he was often under fire. Some expressed surprise that a shell exploding near him did not strike him down. “Any effort at a detailed reconstruction of Lee’s thinking just after noon is mostly guesswork.” (70)

[3] These factors included poor maps and inadequate intelligence. Interestingly, Krick states that A. P. Hill “seems rarely to have put his personal stamp on any battlefield.” (167)

[4] The cover to Volume 1 features this charge as represented in a Don Troiani painting.

[5] Krick is highly critical of D.H. Hill, writing that Hill “squandered his division’s strength during the battle.” (337) Krick respectfully takes issue with the renowned Douglas Southall Freeman’s assessment of Hill’s performance.

[6] Krick gives good marks to Butterfield for his battlefield performance though he questions whether it merited the Medal of Honor he received.

[7] Krick points out that the Irish Brigade “did not fire a shot during the battle” and suffered only one KIA. (771 & 773) I checked my copy of a recent Francis Meagher biography by a prominent, non-Civil War historian and found it repeats this myth. The Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero, Timothy Egan (Boston: HMH, 2016), 209. Noted Civil War artist Don Troiani produced a dramatic work of art, “Brothers of Ireland”, to which Krick alludes, portraying the Irish Brigade in a broad daylight battle charge at Gaines’s Mill relieving the 9th Massachusetts under fire.

[8] “He also copyedited all 420,000 words of the earliest draft, proving anew that fathers will endure any misery to help their children.” (Acknowledgments at ix) Robert K. Krick is the preeminent historian of the Army of Northern Virginia and has written excellent books on the battles of Cedar Mountain and Port Republic, still the standard works for both battles.

Sounds compelling! I have to say, as an aside, I really dislike the new standard of “s’s”. Gaines’ is much simpler and more elegant than “Gaines’s”. No one pronounces the second ‘s’

Completely agree. More elegant, indeed.

Michael: I agree with you. I use “s'” personally although I believe the traditional rule books emphasize “s’s.” I used the latter because Krick uses that form of possessive. The think the rule is becoming more relaxed. A recent book on the battle – A Bloody Day at Gaines’ Mill by Elmer Woodard uses the single “s” possessive.

Where are copies avialable?

William: I received my copies gratis from ABT due to my past donations to ABT’s preservation efforts of this and the intersecting Cold Harbor battlefields. For some time, ABT offered copies to persons donating toward this battlefield(s) but a quick scan of ABT’s website did not show this offer still there (I may have missed it). Given the $29.95 price listed on the back of each volume, one has to believe that public sales should be coming soon. Hopefully, someone-in-the-know reading this review will share that knowledge with us. These books are a must have for avid readers of classic Civil War battle studies.

The Gaines Mill books are now available for order from the Trust website.

The books are marvelous; so is this review !!

Oh of course, I understand why you used it. I also partly understand using “s’s” because it’s just easier than remembering a special exception. But something about it doesn’t look right to me.

I’m halfway through Vol. 2 and this review is both thorough and accurate. The tactical detail is unsurpassed and yet the author has been able to avoid losing the “larger picture” of the fighting throughout.

Because nothing is perfect I do think that the maps could have been better/more illustrative of positions and terrain. That said, a tribute to the narrative is that those elements are made quite clear in the text.

I will second the lack of map details and a lack of comprehensive maps. Somewhat ironic since the author does comment (page 624) on the difficulties of dividing the battle’s events into tidy segments and that such artificial boundaries are less than ideal. I used the ABT map I got in the mail to provide that overview although the details especially of the regiments don’t line up well with the book. Also used Hal Jesperson’s maps but it would of been helpful if the included maps were more detailed and a couple of battlefield wide maps included. Other than that I enjoyed the books to include the notes at the end of the chapter instead at the end of the book.

Mark:

I ended up doing the exact same thing. I knew enough about the battle that I could occasionally look at a map and mentally “expand” the scope but I made frequent use of the ABT maps. FWIW, the maps in Burton’s Seven Days study have the opposite problem.

REL Krick’s superb battle studies make me eager to visit the GM battlefield again! Thanks, Mr. Sinclair, for an excellent review.

I thank you for bringing my attention to this being available. Having now completed it, I find Krick has made a significant number of major deviations from the accepted record. Most notably, he has the Federals abandoning Turkey Hill (the broad plateau with the Watt’s, Adam’s and McGhee farmhouses) and running for the river. He has the 4th Texas etc. attacking the area around the Adam’s House etc and being charged by the cavalry there, and he dismisses the countervailing evidence because it doesn’t fit his beliefs. None of these things is true, and nor his his contention that McClellan had intended on moving to the James before the 24th. He ignores McClellan’s ongoing offensive movements south of the Chickahominy, and the context of the engagement at Garnett’s Hill and Golding’s Farm.

He also has a tendency to overgeneralise from an anecdote. When I’ve followed some of the references, they’re used out of context. He also treats his speculations as fact in places. The maps are awful, with most units doubled on the maps, creating incredible confusion.

He can offer no insight as to how and why the 4th Texas and 18th Georgia pierced the Federal line, in contrast to his fellow park ranger Mike Gorman, whose reading of the ground must remain unquestioned.

It is a useful book for the anecdotes. It is, however, a confusing and in places completely wrong study of the battle. I will review it once I’ve checked up on a few things, but this is less insightful than Burton’s Extraordinary Circumstances.