Remembering the Good: Robert H. Milroy at the Third Battle of Murfreesboro

In Marc Antony’s fictionalized funeral oration in Julius Caesar, the cunning Roman proclaims to the crowd, “The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.” This is frequently the case for Civil War personalities, especially ones with only minor reputations. John D. Barry’s name is inextricably tied to Stonewall Jackson’s, while James H. Ledlie is almost always mentioned in the same breath as the Crater. In some sense, this is fair, as often their moment of memory is also their primary contribution to the conflict. Nevertheless, it was almost never their only, as can be seen in the case of Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy.

Milroy’s sentence in a standard history of the war describes his blinding failures and crushing defeat in the second battle of Winchester in the midst of the Gettysburg campaign. Undoubtedly this was his most crucial moment in the war, and his overall military reputation deserves to be judged largely in light of it.[1] Nevertheless, Milroy showed a different side of his command capabilities in another battle named for an often fought over town: the third battle of Murfreesboro.

Although exonerated of charges relating to his involvement in the Winchester debacle by a court of inquiry, a cloud continued to hang over Milroy’s career. Transferred to the Department of the Cumberland to aid in their recruitment efforts, Milroy began looking for a new battlefield command in order to resuscitate his reputation.[2] Serving as the commander of the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad defenses in the heart of Tennessee when the main scene of conflict for the theater was marching closer to Atlanta, however, did little to reassure him.[3] He personally entreated Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas to give him a command in the Army of the Cumberland, but Thomas denied the request to avoid “committing injustice to competent and worthy Officers who by long service in the Army deserve what advancement the accidents of the service may give them.”[4]

Ultimately, it would not be Milroy going to the war, but the war coming to Milroy that gave him another chance. Lieutenant General John Bell Hood’s decision to lead the Army of Tennessee to recapture Nashville returned Confederates troops en masse to Tennessee’s soil. It also brought a particular foe for Milroy. A firm abolitionist, Milroy held particular disdain for Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, whom he derided as the “bloody hero of Fort Pillow” for his massacre of African-American soldiers.[5] He wished to meet the notorious Confederate cavalry commander in battle, an opportunity granted to him in the third battle of Murfreesboro.

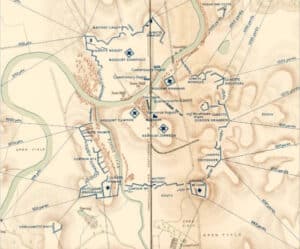

Ordered by Hood to secure the Army of Tennessee’s right flank as they marched to Nashville, Forrest led two cavalry divisions and an infantry division to confront the Union forces in Murfreesboro, where Milroy had been stationed. His commanding officer, Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau, had hurried reinforcements to Milroy in preparation for the likely battle. Now with roughly 8,000 men available to him, Milroy leapt at the opportunity to redeem himself on December 5, 1864.[6]

This haste gave Milroy another black-eye, however. Believing that Forrest’s forces on his front consisted only of dismounted cavalry, he threw the 13th Indiana Cavalry at their position to scatter the Rebels. Although Milroy described their charge being performed “in the most splendid and impetuous style,” the horsemen soon bloodily learned that the Confederate defenses held infantry as well. This forced them to divert the charge with a loss of about forty-two men.[7] Surprised by the presence of Confederate infantry, Milroy advanced some of his own infantry regiments, who drove back the Confederates around 440 yards. As night fell, both sides disengaged, with Milroy returning his soldiers to Fortress Rosecrans to plan his next move.[8]

On December 6, Forrest concluded his 6,000 men could not take Fortress Rosecrans, and by extension Murfreesboro, by storm, so he settled for digging earthworks and setting up a siege to attempt to force the Union onto the offensive. Obliging him, Rousseau sent Milroy with a 3,325-man detachment to drive away the Confederates on December 7. As the Federals moved just as he intended, Forrest devised an ambush for the advancing column. When the Union forces attacked his earthworks and were repulsed, a Confederate cavalry division would charge from the north and close their line of retreat to Fortress Rosecrans. It seemed that Milroy, who had already lost one command to the Confederates, was set to lose another.[9]

But December 7 was not to be a day of infamy for the United States in 1864. Perhaps learning from his impulsivity on December 5, Milroy acted with much greater caution on December 7. This time, he learned of the Confederate positions and their relative deployment from locals before seeking battle. Having driven back a Confederate vedette earlier in the day, Milroy eventually found the main Confederate earthworks. Rather than charging into their teeth once more, as Forrest hoped, Milroy probed them with one of his batteries. When he noticed that the Confederates were not attacking, it seems that he was roughly able to deduce Forrest’s plan, declaring in his post-battle report, “I deemed it prudent not to engage them with my infantry without having the fortress in my rear.”[10]

Withdrawing to a more secure position, Milroy now prepared his men for the attack. In doing so, he had unintentionally placed himself on the left flank of the Confederates. The tables had turned, with Forrest receiving the horrible surprise. First, the skirmishers exchanged volleys. Noting how his skirmishers moved “rapidly, bravely, and in splendid order”, Milroy’s men were able to gain the upper hand and drive back their Confederate counterparts. Now the main lines of soldiers came to blows. For several minutes, the battle hung in the balance. The determination of the Federals struggled against the prepared positions of the Confederates. Milroy recalled, “the roar and fire musketry was like the thunder of a volcano, and the [Union] line wavered as if moving against a hurricane.”[11]

Milroy hurried to the rear to bring forward reinforcements from his second line. The sight of their approach caused the first line to rally and charge the Confederates with a renowned vigor. This, combined with a friendly fire incident amongst the Confederates, put the Rebels to flight. Even the appeals of Forrest himself failed to stem the tide. Milroy pursued the Confederates for half a mile, ultimately coming away with “many … prisoners, one battle-flag, and two fine pieces of artillery (12-pounder Napoleons), with their caissons.”[12]

Fully triumphant over no less an enemy than Nathan Bedford Forrest, Milroy reveled in his redemption. Indeed, he even described the battle in this light in his report to Rousseau, writing, “I avail myself of this opportunity to tender to the major-general … my most grateful acknowledgements for his kindness in affording me the two late opportunities of wiping out to some extent the foul and mortifying stigma of a most infamously unjust arrest, by which I have for nearly eighteen months been thrown out of the ring of active, honorable, and desirable service.”[13] His fellow citizens agreed that he had vindicated himself. Two decades after the general’s death in 1890, the citizens of Rensselaer, Indiana commissioned a monument in his honor.[14] The bronze statue, dedicated on July 4, 1910, serves as a lasting reminder of the complexity inherent to all historic figures, no matter how one-sided they are sometimes cast to be.

Endnotes:

[1] Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964), 326.

[2] Ibid, 326.

[3] Jonathan A. Noyalas, “My Will Is Absolute Law”: A Biography of Union General Robert H. Milroy (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 144.

[4] George H. Thomas to Robert H. Milroy, August 11, 1864, Robert H. Milroy Papers, Jasper County Public Library.

[5] Robert H. Milroy to Mary Milroy, October 3, 1864, Robert H. Milroy Papers, Jasper County Public Library.

[6] Wiley Sword, The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993), 293-295.

[7] Sword, The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah, 295.; U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, 53 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894), Series 1, vol. 45, part 1, 615-616.

[8] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion, 615-616.

[9] Sword, The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah, 296-297.

[10] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion, 617.

[11] Ibid, 617.

[12] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion, 617-618.; Sword, The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah, 297.

[13] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion, 617-618.

[14] “Major General Robert H. Milroy, (sculpture),” Smithsonian, accessed December 4, 2025, https://www.si.edu/object/major-general-robert-h-milroy-sculpture%3Asiris_ari_315006.

All this-including the statue-I never knew. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for this thoughtful scholarship … Milroy redeemed his reputation in his time … and you have redeemed it in ours … good for you!

Gen. Milroy was a cruel military commander of occupied Winchester, Virginia. He would exile entire families because one of them spoke words of encouragement for their boys, fathers or neighbors fighting for the Confederacy in some distant region. “Exile” meant transporting the family some 20 miles out of town and depositing them by the side of the road with no warning. In all weather.

He used “Jessie” scouts – Union soldiers dressed in Confederate uniforms – to knock on doors. The general would then arrest anyone offering ad to this apparent Confederate soldier. He confiscated the Logan home, apparently because it was the largest home in the town. And, his wife wanted something larger. He was a cruel man, motivated by his zeal for abolition. Bless him for wanting to free the slaves, but no blessings for the manner in which he sought it.

Tom