To Err is Human: Mundane Civil War Mistakes With Major Consequences (Part III)

Sometimes what seemed like a mundane mistake could have truly deadly consequences.

Choosing the wrong man for a job nearly results in disaster at Shiloh

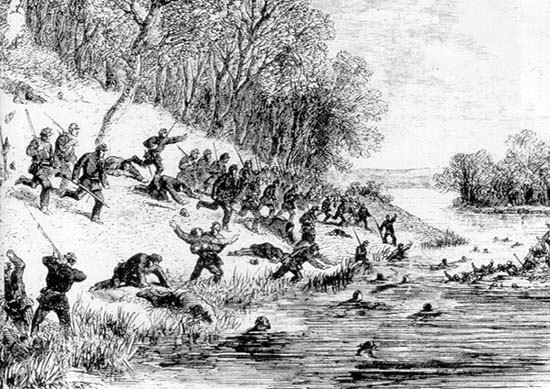

On Shiloh’s bloody first day, critical shortages of ammunition hampered the efforts of the U.S. Army of the Tennessee to defend against the massive assault that CSA Gen. Albert Syndey Johnston’s army launched at 6:00 a.m. on April 9, 1862.[1] Multiple after-action reports described how units were forced back after running out of ammunition during the morning’s heavy fighting.[2] Ulysses S. Grant’s army ended up being driven near the banks of the Tennessee River. The failure to have the ammunition necessary to defend themselves certainly contributed to the horrendous casualties suffered by U.S. forces that first day.[3]

The supply problems arguably were linked to a mistake that might have doomed Grant’s army and even his career. That mistake was ordering Capt. Algernon S. Baxter, Grant’s chief quartermaster and transportation officer, to leave the battlefield and travel by steamboat miles upriver to deliver a message to Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace.[4] By turning Baxter into a courier, a key cog in Grant’s military machine was removed for about four hours during a critical period.[5]

Baxter was responsible for ammunition distribution throughout Grant’s army. He knew where speedily to find the calibers of ammunition needed by each unit and controlled the resupply procedures and transportation. [6] Baxter had been personally selected by Grant for this key position on his personal staff.[7]

Baxter arrived at Pittsburg Landing around 9:00 a.m. in the company of Grant (whose headquarters were 10 miles upstream).[8] Baxter immediately got to work bringing order out of chaos. That is, until an hour later. Then Capt. John A. Rawlins, Grant’s assistant adjutant-general, ordered Baxter to stop his work and carry Grant’s message to Wallace. Why Grant directed Rawlins to assign this role to Baxter is unknown, but it removed Baxter from his true best function.[9]

Grant apparently soon realized his serious error. In his post-battle report, Grant praised by name what he described as “all” of his personal staff for their roles as messengers during the battle, except for Baxter. Indeed, Baxter is nowhere mentioned in Grant’s report, as if Grant wanted to draw no attention to his role.[10] Moreover, in his Memoirs, while mentioning Baxter’s role as a courier, Grant described Baxter as “a quartermaster on my staff,” rather than admitting his key role as the leader of that service.[11]

As described in detail in Scapegoat of Shiloh, after Grant’s conduct at Shiloh came under scrutiny, Grant fixed the blame for the heavy losses of the first day upon Wallace’s supposed negligent failure promptly to reach the battlefield.[12] Grant never admitted that his mistaken choice of a messenger risked the destruction of his army and with it, his rising career.

Mistakes involving missing boats—a constant problem

Mistakes involving boats seem to constitute one of the war’s biggest categories of error. In one of the great understatements of the war, “[w]e are a little short of boats,” reported Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan during the battle of Ball’s Bluff. [13] That shortage contributed to the Union debacle, including the death of Col. (and U.S. Senator) Edward Baker. It helped spark the creation of the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, the bane of U.S. military men throughout the conflict.[14] Quite a price to pay for a “little” boat shortage mistake.

Another little, indeed even “smaller,” mistake involving boats afflicted McClellan only four months after Ball’s Bluff. In February 1862, McClellan planned to capture Winchester, Virginia. The goal was to seal off the lower Shenandoah Valley from Confederate raids while McClellan moved his army around the main Confederate force. To ensure the safe movement of troops into the Valley, boats were ordered to proceed along the B&O Canal to assist in the construction of a bridge across the Potomac River. Unfortunately, no one bothered to measure the width of the boats as compared to the canal locks. As it happened, the boats were six inches too wide to pass the locks. This embarrassing mistake was compounded by wags who derided the failure of the previously ballyhooed campaign as dying of “lock-jaw.” Lincoln became even more frustrated with McClellan, demanding to know why McClellan did not determine if the boats could pass the locks “before spending a million dollars getting them there?” The incident contributed to a souring relationship between Lincoln and McClellan.[15] All over six inches.

At least McClellan got boats, albeit the wrong size. By contrast, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside relied on pontoon boats being available for a quick crossing of the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in December 1862. Instead, a misunderstanding left a pontoon-less Burnside sitting on the wrong side of the river for over a week. This allowed Gen. Robert E. Lee to seize commanding ground. The result was the debacle of the battle of Fredericksburg.[16]

Yet another Union general did get boats, of the right size, but not quite enough. In November 1863 Maj. Gen. William French’s III Corps led George Meade’s Army of the Potomac on its Mine Run Campaign. French’s first job was to bridge the Rapidan River. French’s engineers started off well, but found themselves one pontoon short of reaching the far bank. This mistake forced a delay of several hours. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of other troops sat around waiting their turn to cross, throwing the entire operation off schedule, contributing to its ultimate failure. All due to a mistaken count of boats needed to bridge a river.[17]

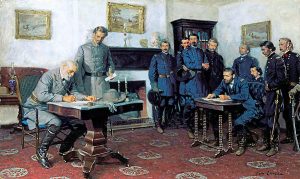

At least the “bridge gods” did not play favorites. After evacuating Petersburg and Richmond on April 2, 1865, Lee sought to consolidate his army at Amelia Court House. However, Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s command was barred from its intended escape route over the Appomattox River by the failure of “some one” to have a pontoon bridge set up and ready for the crossing. In a message he sent on the evening of April 3, Lee warned Ewell of the mishap, which endangered his hope of keeping his head start on Grant: “When you were directed to cross the Appomattox at Genito Bridge, it was supposed that a pontoon bridge had been laid at that point, as ordered. But I learn today…that such is not the case.”[18]Ewell had to search for another way to cross the river and join Lee. The resultant delay contributed to Lee’s failure to outpace pursuing U.S. forces, leading to disaster at Sailor’s Creek and ultimately, Appomattox Court House.[19]

As shown, mistakes made during the Civil War came in various types, sizes and consequences, some not as immediately obvious as others. Yet all these seeming mundane mistakes mattered to the history of the war. As the hoary nursery rhyme goes, “For want of a nail…a kingdom was lost.”

[1] Ron Chernow, Grant (Penguin Press, New York, NY, 2017), pp. 198-199.

[2] Kevin Getchell, Scapegoat of Shiloh: The Distortion of Lew Wallace’s Record by U.S. Grant (McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2013), pp. 125-126, 135-136, 140-144, 146-147, 153-162, 175.

[3] Getchell, pp. 98, 99, 150, 155, 177; Chernow, p. 204; Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, Fort Sumpter to Perryville (Vol. I) (Random House, Inc., New York, NY, 1974), p. 350.

[4] Getchell, pp. 141-143, 145, 165-166.

[5] Getchell, pp. 120, 153, 176-178.

[6] Getchell, pp. 39, 95, 141-143, 145.

[7] Getchell, pp. 11-13.

[8] Getchell, pp. 27-28, 37-39, 79-80, 102-103, 153, 166.

[9] Getchell, pp. 145, 147, 148-152, 165-166, 169.

[10] Getchell, pp. 101, 153, 172.

[11] Ulysses S. Grant, John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo, Eds., The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2017), p. 232 (emphasis supplied); Getchell, p. 153.

[12] An April 23, 1862 telegram from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to Grant’s superior stated that “The President desires to know…whether any neglect or misconduct of General Grant or any other officer contributed to the sad casualties that befell our forces on Sunday.” Getchell, pp. 172-173; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I, Vol. X, Pt. 1 (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1880-1901), pp. 98-99, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077730160&seq=116 (hereafter “OR”).

[13] OR, Ser. I, Vol. LI, pt. 1, p. 499, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951002188671r&seq=511.

[14] Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War (University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1998), pp. 22-23, 55-56, 62-63.

[15] Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan, The Young Napoleon (Ticknor & Fields, New York, NY, 1988), pp. 73, 156-158; Walter Coffey, “Everything Seems To Fail,” The Civil War Months (February 27, 2022), https://civilwarmonths.com/2022/02/27/everything-seems-to-fail/.

[16] Stephen E. Ambrose, Halleck: Lincoln’s Chief of Staff (Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, LA 1996), pp. 95-98; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1988), pp. 570-572; Tap, pp. 142-143.

[17] John G. Selby, Meade: The Price of Command, 1863-1865 (Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2018), pp. 101-106.

[18] Burke Davis, To Appomattox: Nine April Days, 1865 (Eastern Acorn Press, New York, NY, 1992), pp. 164-165; William Marvel, “Many Have Offered Excuses for the Confederate Retreat to Appomattox,” Appomattox Commemorative Issue (Primedia History Group, Leesburg, VA, 2005), pp. 42, 44, 47; “Ewell Crosses the Appomattox Racing West: Lee’s Retreat,” The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=256172.

[19] Marvel, pp. 48-49, 85; Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, Red River to Appomattox (Vol. III) (Random House, Inc., New York, NY, 1974), pp. 910-919.

To err is human, but to mendaciously cover it up and then slander and scapegoat a fellow officer is outrageous. But then Sam Grant, like Bobby Lee in Ye Olde Days to his acolytes, walks on water.

Another nice piece, thanks … although I believe author Getchell’s hanging the outcome of Shiloh on Grant’s choice of couriers is a stretch, along with his other rationale regarding Wallace’s late arrival to the fight.

Here’s a plausible explanation that is not “inexplicable” … perhaps Grant, realizing Wallace’s division was far out of position, directed Rawlins to order Baxter, a trusted officer to get Wallace moving … or perhaps Rawlins, who knew Grant’s intent, like any good Chief of Staff, made that call himself, like any good Chief of Staff would have done … and it did take Wallace too long to get in the fight, nothing “supposed” about that … finally, it sounds like Getchell argues that Baxter (who was a staff officer) was the only member of the entire Quartermaster organization that knew anything about the location of ammunition — that’s a hard one to swallow.

Mark, thank you. Yes, one could certainly argue over Getchell’s conclusion but he makes an interesting argument, including that Baxter was such a key player due to a rush of work in the very days leading up to the battle in collecting/organizing ammunition, which I suppose may have made his knowledge more critical. He also claims, based on dubious evidence, that Grant was drunk at Shiloh. I do not buy that at all. He also condemns Grant for locating his headquarters so far from Pittsburg Landing. Not a Grant fan at all.