“My Paramount Object in this Struggle:” Lincoln’s Public Letter to Greeley

ECW welcomes back guest author Don Zavodny.

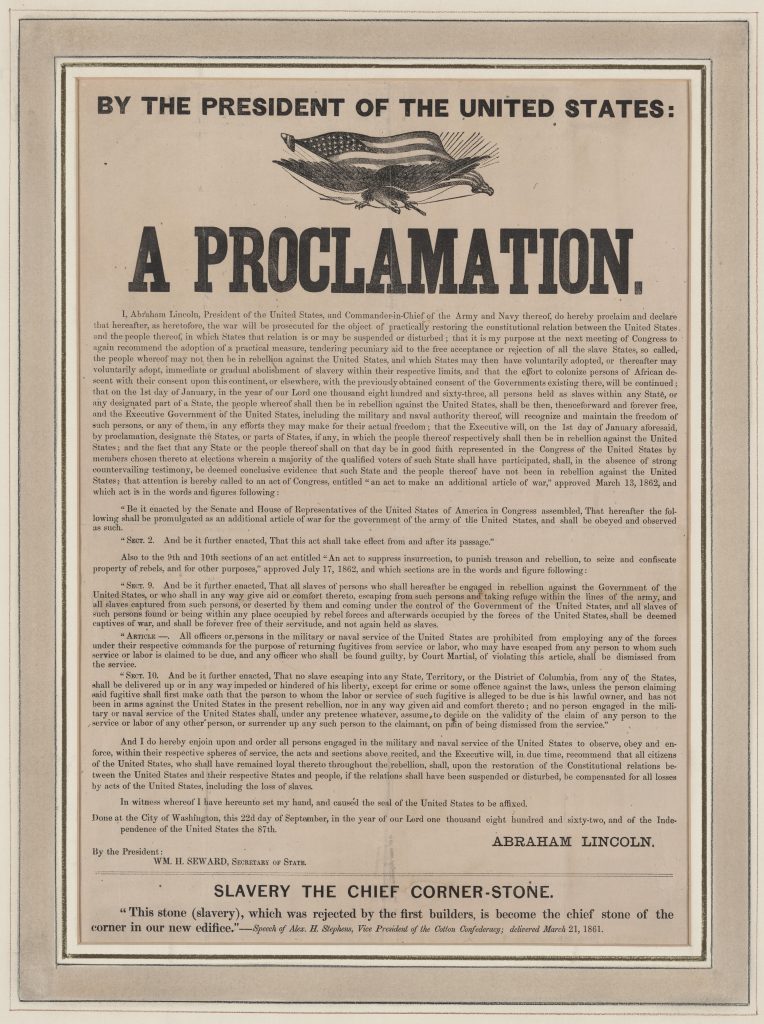

President Abraham Lincoln’s most well-known public letter was his reply to Horace Greeley, the Republican editor of the New York Tribune, who published an editorial in the form of an open letter criticizing the president on August 20, 1862. Lincoln’s response appeared three days later in a rival newspaper and declared that his paramount object was not to save or destroy slavery, but to preserve the Union. When the president wrote these words, he had already read his draft of the proposed emancipation proclamation to his cabinet on July 22, which ordered that slaves in any state still in rebellion shall be “forever free.” Lincoln chose to wait to issue the proclamation until it could be supported by a major Union military victory, which he hoped would come sooner rather than later. Amid Lincoln’s long wait, his public letter to Greeley was intended to appeal to multiple groups regarding his policy, and thus a simple reading of the text has puzzled both contemporaries and scholars.[1]

Lincoln’s reluctance to publicly declare his support for emancipation infuriated many radical abolitionists at the time, such as Wendell Phillips, who denounced the letter “as the most disgraceful document that ever came from the head of a free people.”[2] Lincoln has also been criticized by some historians who later questioned his commitment to emancipation. Historian Barbara Fields wrote that the president was “still trapped in his own obsession with saving the white Union at all costs, even the cost of continued black slavery.”[3] While Lincoln’s reply to Greeley was written with political considerations in mind designed to demonstrate his overriding objective was to save the Union, it has often been misunderstood. In fact, with his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation waiting in his coat pocket, his letter provides a preview and justification of his imminent policy to free the slaves, with the only unanswered questions being when and how many.

Understanding the context of events and Lincoln’s precise use of language demonstrates his decision to act on emancipation was only a matter of time. During the two months before Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, he worked to prepare white public opinion and conservative elements of his fragile Union coalition in the North for emancipation using a planned public relations campaign. While the president’s efforts to shape public opinion were never as well coordinated and calculated as some scholars have argued, his letter to Greeley shines as the most effective example of this strategy.[4]

The president’s message had already been largely written, and he only needed the opportune moment to issue it to the public, which Greeley provided. Still, Lincoln was likely annoyed that Greeley failed to write to him privately, which motivated the president to defensively refer to a direct quote from the Tribune editor’s letter about the “policy you seem to be pursuing.” In his editorial, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” Greeley demanded that the president order his generals to vigorously enforce the emancipation provisions of the recently passed Second Confiscation Act, writing “We require…that you EXECUTE THE LAWS.”[5]

Lincoln wrote that he was determined to defeat the rebellion and save the “Union as it was.” This often used phrase by Democrats was appropriated by Lincoln to show he had no intention of violating the Constitution’s protections for slavery. In fact, this had long been Lincoln’s position since 1854, as he had previously argued that the peculiar institution was protected in the states where it existed, and that he only desired to prevent slavery from expanding into the western territories. At the same time, he warned that the old Union with slavery intact would be more difficult to maintain the longer the war continued. Lincoln then eloquently declared his statement of policy regarding emancipation and the Union:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.[6]

This passage can be interpreted in many ways, but it shows that Lincoln was opposed to being forced to choose between two extremes, of either saving or destroying slavery, regardless of whether it risked the preservation of the Union. While he could not yet say so publicly, he now came to the conclusion that he likely would never be able to defeat the rebellion and save the Union without destroying slavery as well. However, Lincoln’s finely crafted message was part of his strategy to appeal to the border states and conservatives in the North, including Democratic army officers, common soldiers, and poor white immigrants, all of whom feared the war might degenerate into a crusade for abolition and would lead to an influx of free blacks who would compete for jobs with white workers.[7]

Significantly, while saving the Union was Lincoln’s paramount goal, this meant it was his principal, but not necessarily his only, objective. By this point in the war, the old Union was no longer possible, and he indicated that he had the authority to take action against slavery, even though he was not yet ready to announce it publicly.[8]

By the summer of 1862, the consequences of the war already precluded two of his three options regarding slavery. Earlier in the year, Congress had abolished slavery in the District of Columbia and in the western territories. Furthermore, the federal government’s contraband policy, which accepted runaway slaves into the safety of the Union army lines, had resulted in the de facto freedom of thousands of slaves in the South. Lincoln had no intention of returning these individuals to bondage. However, slavery was still legal and constitutionally protected in the loyal border states.[9]

Thus, it was no longer possible to save the “Union as it was.” Thousands of slaves were already seizing their freedom in the rebel states, but the institution still remained legal in the border states, for now. It was a political and military reality that the only likely option remaining was to preserve the Union and free at least some slaves in the Confederate states, which was already underway.[10]

Lincoln had been under growing pressure in much of the North to act on emancipation. Mindful of this, he was hopeful that he would soon have the opportunity to respond to that demand if Gen. John Pope’s newly formed Army of Virginia could secure a decisive victory against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.[11]

Lincoln ended his letter by appealing to anti-slavery supporters and hinted that action may be forthcoming if necessary, writing that he shall do more or less if he believes it will help save the Union. Finally, he made a distinction between his view of “official duty” as president and his “oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free,” reminding the public that he had consistently advocated for the ultimate extinction of slavery.[12]

Even though Greeley, anti-slavery Republicans, and abolitionists might not be completely satisfied by Lincoln’s letter, he knew their attitudes would change once he announced the proclamation, because it would be far more sweeping than the Second Confiscation Act could ever have been. Lincoln believed that only the president as the commander-in-chief could exercise war powers to free slaves in states in rebellion. At the same time, the president needed to frame his policy as being dedicated to preserving the Union above all, in a way that would be acceptable to the border states and his fragile Union coalition, in order to avoid negatively impacting vulnerable Republicans ahead of the upcoming midterm elections in the fall.[13]

Lincoln’s letter was universally praised throughout much of the North. The moderate New York Times approved and predicted the president would patiently wait for the right moment to announce emancipation when “it can be taken with effect, and be made instrumental in preserving the Union.” Conservative Republican operative Thurlow Weed was especially satisfied, writing that Lincoln’s message was a clear and energetic statement of policy to save the Union and was “expressed so clearly that all who read must understand.” Even conservative, anti-emancipation newspapers like the New York Journal of Commerce, were convinced that Lincoln’s message would “touch a response in every American heart.”[14]

Lincoln continued to communicate directly with the Northern public during the war through the skillful use of the public letter. For the moment though, he held together his Unionist coalition, while signaling that he had the authority to use the emancipation lever if the war demanded it. The president’s desire to issue his freedom decree was delayed by yet another military reverse in Virginia, and was only realized after the nation suffered its bloodiest day along Antietam Creek on September 17, 1862.

Don Zavodny lives in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and teaches secondary school in Maryland. He was previously an Educator and Interpreter with the Texas Historical Commission at the Bush Family Home State Historic Site in Midland, Texas. He graduated with a B.A. in history from the University of Houston in 2011 and an M.A. in American history from Gettysburg College in 2023. He recently authored two articles about Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation in the Lincoln Herald journal.

Endnotes:

[1] Lincoln to Greeley, August 22, 1862, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Roy P. Basler, ed., vol. 5 (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 388-389 (hereafter cited as CW); “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” New York Tribune, August 20, 1862; Harold Holzer, Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014), 394-400; David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Shuster Paperbacks, 1995), 365-366.

[2] Wendell Phillips to Sydney Howard Gay, Sept. 2, 1862, Gay Papers, Columbia University.

[3] Barbara J. Fields, “Who Freed the Slaves?” in Geoffrey C. Ward, The Civil War: An Illustrated History (New York, 1990), 181.

[4] Holzer, Lincoln and the Power of the Press, 396-397; Donald, Lincoln, 368-369; Mark E. Neely, “Colonization and the Myth That Lincoln Prepared the People for Emancipation,” Lincoln’s Proclamation: Emancipation Reconsidered, ed. Blair, William A. and Karen Fisher Younger (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 65-67.

[5] “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” New York Tribune, August 20, 1862, Donald, Lincoln, 364-365; CW, 5: 388-389.

[6] CW, 5: 388.

[7] Donald, Lincoln, 368.

[8] Donald, Lincoln, 368.

[9] Oakes, Freedom National, 313.

[10] Oakes, Freedom National, 313.

[11] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 489.

[12] CW, 5: 388-389.

[13] Donald, Lincoln, 365.

[14] New York Times, August 26, 1862; Weed to Seward, August 23, 1862, and Weed to Lincoln, August 24, 1862, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress; New York Journal of Commerce, August 27, 1862.

An excellent and well-written analysis. Thank you for the read!

Thank you. Clear article that makes me think Blondin was Lincoln reincarnated.

To save the union? Maybe geographically but not one in harmony spiritually and truth, just take a look around.