Justice Deferred: Lincoln, Stanton, and the Fate of the Coles County Fifteen

ECW welcomes back guest author M.A. Kleen.

“Every damn one of them should be hung.” The words of Edwin Stanton, bespectacled U.S. secretary of war, cut through the air like a verdict. His white-streaked beard forked down over a black waistcoat.

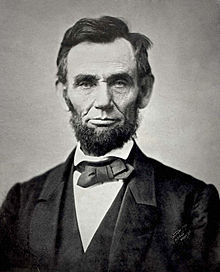

Dennis F. Hanks, childhood friend and second cousin of President Abraham Lincoln, shifted uneasily in the cramped, dusty second-floor office of the White House.

When Hanks arrived, he carried more than letters from home. He came to speak on behalf of fifteen prisoners held at Camp Yates in Springfield, Illinois, delivering the pleas of their friends and families, who urged that the men be tried in civilian court or released entirely.

According to Lincoln’s former law partner, William H. Herndon, who later interviewed Hanks, Lincoln replied, “If these men should return home and become good citizens, who would be hurt?”[1]

Stanton, wearing a bobtail coat, scoffed. The fifteen prisoners facing a military tribunal were among dozens arrested in east-central Illinois after the deadly riot in Charleston, Coles County, on March 28, 1864. Union soldiers had been killed and wounded. Someone, Stanton argued, had to “take hard punishment.”[2]

Outside, the late spring heat had settled in. Grant and Lee’s armies were locked in brutal combat around Spotsylvania Court House. In Georgia, Sherman was driving toward Atlanta. The weight of these events hung heavily on the minds of both Lincoln and Stanton.

At an impasse, Stanton brusquely left the office, pushing past the crowd of petitioners waiting to see the President.

“Abe,” Hanks said, visibly annoyed, “if I’s as big as you, I would take that little feller over my knee and spank him.”

The president laughed. “It is not easy to keep my cabinet all in good humor,” he reportedly said.[3]

Six weeks earlier, the Charleston Riot had shocked the fractured nation. It was among the deadliest home-front uprisings of the Civil War, and it happened in Lincoln’s own backyard. His stepmother lived in Coles County, and he still had many friends and relatives in the area, including Dennis Hanks.

What began as a political confrontation between Democrats opposed to the war, known as Copperheads, and Union soldiers home on veteran furlough quickly spiraled into gunfire. The incident left nine soldiers and civilians dead and twelve wounded, sparking mass arrests that began as soon as the smoke cleared.

Despite a superficial abdominal wound, Col. Greenville McNeel Mitchell, Charleston native and commander of the 54th Illinois Infantry, set out with 75 mounted men in pursuit of the attackers as soon as Lt. Col. Augustus H. Chapman arrived with reinforcements from nearby Mattoon.[4]

As they retreated from town, Coles County Sheriff John H. O’Hair and the Copperheads captured a Union private named Levi Freesner, who had no idea what had just occurred. O’Hair persuaded the group to spare Freesner’s life. After cutting a telegraph wire and stopping for supper, they brought him to a farmhouse owned by Miles Murphy and left him there under guard. The rest of the group then disbanded, agreeing to regroup the following morning.

Meanwhile, Col. Mitchell’s patrol was rounding up stragglers. Shortly after midnight, they freed Pvt. Freesner and captured his guards. Over the following days, they arrested nearly fifty men. When the Copperheads later regrouped to plan their next move, their numbers had noticeably dwindled. Hotheads proposed returning to “clean out” Charleston, but they were overruled. Sheriff O’Hair was nowhere to be found; he was already en route to Canada as local Republicans ransacked his home.[5]

Rumors swirled that hundreds of Copperheads were arming and gathering in the area, preparing to launch an attack. The 41st Illinois and 47th Indiana regiments were dispatched to Coles County as reinforcements. From the night of April 2 to April 4, Col. Mitchell once again led a mounted patrol, this time taking a circuitous route through east-central Illinois. “I found bodies of men from 25 to 100 had been seen, but had dispersed,” he later reported. “At present all is quiet.”[6]

Following interrogations, 29 prisoners were held and sent to Camp Yates in Springfield, Illinois, under the authority of Lt. Col. James Oakes of the 4th U.S. Cavalry, assistant provost marshal general for Illinois. Oakes released thirteen of them, and one, Miles Murphy, died of illness on April 17. That left fifteen men in federal custody.

Shortly after Dennis Hanks returned from Washington, DC, a special grand jury convened in Coles County to examine the evidence and issue indictments, which were handed down in early June. The grand jury indicted fourteen participants in the riot, but only four, George Washington Rardin, John F. Redmon, Bryant Thornhill, and Jefferson Collins, were among the prisoners held at Camp Yates.[7]

President Lincoln took a personal interest in the case, requesting that all related court records and depositions be sent to him, which both Lincoln and Lt. Col. Oakes described as “voluminous.”[8]

On June 12, after 77 days of confinement, the fifteen prisoners co-signed a letter to Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman, commander of the Northern Department, requesting their release. Their attorneys, Orlando B. Ficklin and Milton Hay, filed for, and were granted, a writ of habeas corpus by the Fourth Circuit Court. However, before the release could take effect, President Lincoln suspended habeas corpus in their case, and the men were remanded to Fort Delaware.[9]

Secretary Stanton and the Army wanted the case kept out of civilian courts. After all, it was Union soldiers who had been targeted in the riot. Major Addison A. Hosmer, acting judge advocate general, and Oakes recommended that the prisoners be tried under military law. To them, the evidence pointed to a seditious conspiracy.[10]

Lincoln wasn’t so sure. His initial instinct was to order the prisoners’ release, but by mid-July he reversed course to allow time to review all the evidence. Pressure mounted from all sides; letters and petitions flooded in from Illinois, while the Army urged him to stand firm.

Orlando Ficklin, who had witnessed the riot from inside the courthouse, traveled to Washington, D.C., in July, though it’s unclear whether he met with the president. A Democrat, Ficklin had served alongside Lincoln in Congress and had shared courtrooms with him in their early legal careers. They exchanged letters during Ficklin’s time in Washington, but he ultimately returned to Illinois empty-handed.[11]

As summer gave way to autumn, the ongoing war and the approaching election consumed the president’s attention. The fall of Atlanta on September 2 and Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s victories in the Shenandoah Valley greatly improved Lincoln’s chances for reelection. On November 4, just four days before the vote, Lincoln penned a brief note on the cover of Maj. Hosmer’s July 26 report and forwarded it to the War Department: “Let these prisoners be sent back to Coles County, Ill., those indicted be surrendered to the sheriff of said county, and the others be discharged.”[12]

By November 14, the fifteen prisoners were en route to Illinois by train. The two indicted for murder in connection with the Charleston Riot, George Washington Rardin and John Redmon, were exonerated at trial in December 1864.[13] Rardin, age 29, died less than a year later.

After the war, John H. O’Hair and the other indicted rioters who had fled quietly returned to their farms. The cases were reopened in 1871, but two years later, following the election of a new Democratic state’s attorney, James W. Craig, they were finally dismissed. O’Hair didn’t live to see the outcome, dying of illness on October 7, 1872.[14]

Remarkably, none of the participants were ever held legally accountable for their roles in the riot. Over time, Unionists and Copperheads in east-central Illinois set aside their old animosities and found a way to live peacefully alongside their former adversaries.

M.A. Kleen is a program analyst from northern Virginia and editor of spirit61.info, a digital encyclopedia of early Civil War Virginia. His article “‘A Kind of Dreamland’: Upshur County, WV at the Dawn of Civil War” appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Ohio Valley History.

Endnotes:

[1] William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Abraham Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life, Vol. II (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1924), 229. Herndon’s account of the riot and its aftermath contains several factual errors, including the wrong year.

[2] Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Vol. 1 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1939), 616.

[3] Charles H. Coleman, Abraham Lincoln and Coles County, Illinois (New Brunswick: Scarecrow Press, 1955), 230-231. Hanks gave several versions of this conversation. According to Herndon, Lincoln said, “If I did, Dennis, it would be difficult to find another man to fill his place.” Herndon and Weik, Abraham Lincoln, 230.

[4] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. XXXII, Part 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 634.

[5] Richard K. Tibbals, “‘There has been a serious disturbance at Charleston…’: The 54th Illinois vs. the

Copperheads,” Military Images 21 (July-August 1999), 15; Charles H. Coleman and Paul H. Spence, “The Charleston Riot, March 28, 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 33 (March 1940), 31-33.

[6] Official Records, Series I, Vol. XXXII, Part 1, 631, 634.

[7] Peter J. Barry, “The Charleston Riot and its Aftermath: Civil, Military, and Presidential Responses,” Journal of Illinois History 7, no. 2 (Summer 2004), 89-90.

[8] Official Records, Series I, Vol. XXXII, Part 1, 631; Coleman, 228.

[9] Barry, 90; Peter J. Barry, “‘I’ll keep them in prison a while …’: Abraham Lincoln and David Davis on Civil Liberties in Wartime,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 28, no. 1 (Winter 2007), 22.

[10] Official Records, Series I, Vol. XXXII, Part 1, 632-633.

[11] Coleman, 227-229; Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. VII (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press), 455.

[12] Official Records, Series I, Vol. XXXII, Part 1, 643.

[13] Barry, “The Charleston Riot and its Aftermath,” 103.

[14] Barry, “The Charleston Riot and its Aftermath,” 106.

Great article. Thank you. I knew nothing about the Charleton Riots. Very informative.

Thank you! I have a couple others about this topic on ECW you might want to check out too

thanks, good story … like the snake, those Illinois Copperheads could be very dangerous characters … i had no idea!

Thank you!

Where can I find a printed copy of this? George Washington Rardin is my husband’s 2x great grand-uncle and I would like to have it to put in his file.

Very cool! You should be able to print this article, that’s the only way to get a hard copy.

Michael, very interesting. Thank you for sharing. Questions. You write that “George Washington Rardin and John Redmon, were exonerated at trial in December 1864.” It appears that that was that a civil trial? If so, any idea why Lincoln decided to reject the Army’s plea that they be tried under military law (i.e., a military commission)?

That is curious, as during the same general period, specifically October 1864, several civilians were tried by military commission in Indiana, with some sentenced to death. The case of one, Lambdin Mulligan, went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1866 that the military could not try civilians in areas in which the civil courts were functioning.

That’s a great question. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen anything that reveals Lincoln’s reasoning for ordering their release from military custody. The difference between this and other similar cases is probably that Lincoln had so many personal connections to it. Even Republicans were lobbying to have the cases tried in civilian court, so maybe he just relented? I’m not sure