The Destiny of the Republic, Touched with Fire—The Story of James Garfield

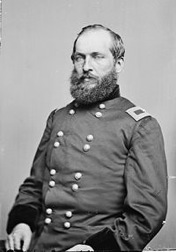

I’m reading Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President, Candice Millard’s new biography on the presidency and assassination of James A. Garfield—one of the least-known of the mediocre bearded Gilded Age presidents. Millard is a tremendous storyteller, and her book is, so far, outstanding.

I’m reading Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President, Candice Millard’s new biography on the presidency and assassination of James A. Garfield—one of the least-known of the mediocre bearded Gilded Age presidents. Millard is a tremendous storyteller, and her book is, so far, outstanding.

She definitely has a big crush on Garfield, though, painting him with almost martyr-like strokes, which will of course be important as a rhetorical tool for making readers more sympathetic to Garfield’s assassination.

But I know a very different Garfield, much of it informed by his Civil War service.

James M. Perry’s Touched with Fire: Five Civil War Presidents and the Battles that Made Them is one of my favorite general audience Civil War books because it covers, in excellent narrative fashion, a quirky, interesting topic. Much has been written about the number of military heroes who’ve later ascended to the presidency—George Washington, first and foremost, but Ulysses S. Grant, Eisenhower, etc., etc.

James M. Perry’s Touched with Fire: Five Civil War Presidents and the Battles that Made Them is one of my favorite general audience Civil War books because it covers, in excellent narrative fashion, a quirky, interesting topic. Much has been written about the number of military heroes who’ve later ascended to the presidency—George Washington, first and foremost, but Ulysses S. Grant, Eisenhower, etc., etc.

The mediocre bearded Gilded Age presidents tend to get overlooked because of their unremarkable tenures. Grant gets attention because his successes as a war hero served in such stark contrast to his failures as a president (that’s a topic for a future post!). Hays gets a mention because he lost the popular vote but, through last-minute backroom dealing, won the electoral vote. Garfield gets a mention because he was assassinated a few months into his tenure. “Garfield remains the mystery man,” Perry says. “He was probably the smartest of the lot; he was also the most devious.”

That’s quite different than the portrait Millard paints of Garfield, who describes him as a man who “had risen quickly through the layers of society, not with aggression or even overt ambition, but with a passionate love of learning that would define his life.” She writes about Garfield’s “deep admiration for mathematics and the arts” and his belief that “science, above all other disciplines…has achieved the greatest good.” That particular theme becomes important to her overall angle on Garfield’s story.

That’s quite different than the portrait Millard paints of Garfield, who describes him as a man who “had risen quickly through the layers of society, not with aggression or even overt ambition, but with a passionate love of learning that would define his life.” She writes about Garfield’s “deep admiration for mathematics and the arts” and his belief that “science, above all other disciplines…has achieved the greatest good.” That particular theme becomes important to her overall angle on Garfield’s story.

Millard also capitalizes on Garfield’s log-cabin poverty as a boy and his rise to success—something his campaign biographers capitalized on, too—and she paints him as a devoted family man.

Perry, on the other hand, calls out Garfield as “a notorious womanizer” and a political “schemer.”

Perry does not spend much time on any of the presidencies of the mediocre bearded men—and with Garfield, there are only 200 days to look at, anyway—but instead spends considerable time telling the stories of their military service in the war. He bases his portrait of Garfield on that; Millard virtually ignores it.

Perry first outlines Garfield’s service as Colonel of the 42nd Ohio, where he outmaneuvered Confederate forces in Kentucky that outnumbered and outexperienced him. After his promotion to brigadier general for those successes—a promotion that made him the army’s youngest general at age 30—he served as a member of the court for Fitz John Porter, brought up on charges of disobedience and disloyalty following his performance at Second Manassas. Porter was exactly the kind of nabob “professional soldier” Garfield scorned as incompetent, autocratic, and tyrannical, “little understanding that running a volunteer army was a lot different from running a professional one,” Perry says.

(“West Pointers, in their defense,” Perry goes on to say, “believed that these civilian generals were often more interested in advancing their political careers than in defeating the enemy. Garfield was the sort of general they had in mind.”)

At around that same time, Garfield was elected to Congress. During the highly political climate of the time, his wife, Crete, wrote to him: “I don’t know but politics is to be the death of you yet.” Prophetic words.

Although successfully elected, Garfield didn’t have to report for duty until December of 1863, so he continued his service in the army. He was assigned to duty as chief of staff for Major General William S. Rosecrans. Perry credits Garfield as being the real brains behind Rosecrans’ Tullahoma campaign, “a brilliant campaign of maneuver” that drove Confederates out of Tennessee with virtually no fighting.

While initially supportive of Rosecrans, Garfield eventually grew frustrated with Rosecrans’ slowness. “Thus far the General has been singularly disinclined to grasp the situation with a strong hand and make the advantage his own,” he wrote to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, a confident and chief political sponsor. Garfield’s ongoing correspondence ultimately played a role in Rosecrans’ removal from command, although by that point, Garfield was sitting in his Congressional catbird seat.

Biographer Kenneth Ackerman, author of Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield, points out that the congressman and later-president ever-after preferred to be called “General.”

Biographer Kenneth Ackerman, author of Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield, points out that the congressman and later-president ever-after preferred to be called “General.”

“[A] title of “General”—especially one like Garfield’s, earned on Civil War battlefields—easily outranked “Congressman,” “Senator,” or even “President,” Ackerman writes.

Millard’s book positions Garfield as a reluctant candidate. “This honor comes to me unsought. I have never had the Presidential fever; not even for a day,” Garfield said after the Republican party chose him on the 36th ballot at a highly contentious convention.

And indeed, as Ackerman also tells it, Garfield tried to ignore early talk of himself as a dark horse candidate even before the convention started—but for more practical reasons. “He had committed himself publicly to support fellow Ohioan John Sherman, longtime senator and now treasury secretary under President Hayes [and brother of General William T. Sherman],” Ackerman writes. “Any hint of disloyalty would spell disaster. Sherman would never forgive Garfield for any betrayal, and would surely avenge himself by sinking any political future Garfield might have.”

Sherman had picked Garfield to deliver his nominating speech, in fact, as a way to take Garfield off the table as a political rival, which Millard does point out. But to further suggest, as she does, that Garfield wasn’t up to his neck in political machinations is a bit disingenuous—although I think she does it solely as a way to focus her excellent story.

In fact, Garfield was up to his eyeballs in political struggle, including a two-day fight over a rule that could’ve railroaded Ulysses S. Grant into a third term. Garfield fought against it. “I regard it as being more important than even the choice of a candidate,” he told a reporter from the Chicago Tribune.

Millard later makes an astounding statement a little harder to ignore. “Garfield did not show a great deal of interest in the election,” she says. Aside from “an occasional trip to the office behind his house to see what news had come over the telegraph, he went about his normal routine” on election day.

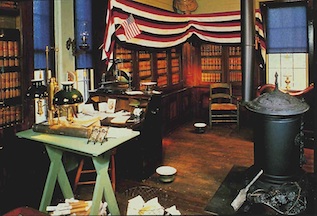

Wait, wait, wait—the guy had a telegraph office built in his back yard so he could handle campaign work and monitor elections results. That hardly seems like a lack of interest. The Garfield campaign also went so far as to transport thousands of people by railroad to Garfield’s home in Mentor to hear him speak since it was considered unseemly for the candidate to stump for himself.

The campaign was particularly stressful for Garfield for several reasons, not least of all because one of the men he’d beat out for the nomination was Grant. Would the former president and still-beloved war hero campaign for him? Party loyalty didn’t mean a lock, especially since the Democratic candidate was Winfield Scott Hancock, one of Grant’s most trusted subordinates and a beloved war hero in his own right.

By 1880, though, the relationship between Grant and Hancock had become strained. After weeks of post-convention silence, Grant finally spoke up in favor of Garfield and soon hit the campaign trail on his behalf, the first former president to stump for his party’s ticket. “I have known [Hancock] for forty years,” Grant said, harkening all they way back to their days at West Point together. “He is a vain, weak man. He is the most selfish man I know.” (For details on all this, check out Ackerman’s book, which offers the best treatment of the relationship between Garfield, Grant, and Hancock during the election.)

I look forward to continuing my way through Millard’s book, which really is a great piece of storytelling. As a writer, I can understand why she focuses the way she does in an attempt to shape a particular interpretation of events and, more importantly, tell a damn good story. And believe me, she tells a damn good story.

But I’m chuckling a little, because the Garfield she obviously admires is a different man than the one I’ve come to know over the years. I am anxious to see how she carries the story forward and so see how she approaches the question that, I think, haunts the end of Perry’s book.

“What would a Garfield presidency been like?” he asks.

It’s an intriguing question, for Garfield was the smartest, most devious, and the most political of all these Civil War president. He was not the sort of man who would have accepted the conventional wisdom in the Gilded Age that presidents really were better off seen and not heard. The question, with Garfield, was always one of character. Still, he was aggressive, ambitious, and knowledgeable. He had possibilities.

After listening to an interview with Candice Millard on NPR, I am so glad to read this post. Her characterization of Garfield’s nature, as Chris Mackowski aptly conveys here, bears absolutely no resemblance to accounts of his Civil War service. He was known universally in the Army for notorious self-aggrandizement. For example, in Peter Cozzens’s “This Terrible Sound”: “Garfield’s colleagues saw him for what he was–an ambitious man who would measure his loyalty to his commander [Rosecrans] by its utility in furthering his political or military career. Few were as taken with Garfield’s military abilities as he himself seemed to be.” As to Perry’s calling Garfield “the real brains behind Rosecrans’ Tullahoma campaign,” Cozzens’s account would dispute that as well. Garfield did advocate action in Tennessee, but as a way of pre-empting his commander for his own benefit vis-a-vis Washington higher-ups, since Garfield confidentially knew that Rosecrans had already decided on the campaign (Cozzens, pp. 16-17). Besides, as one of the most intellectually brilliant Union generals, Rosecrans suffered no shortage of brains! Although fascinated with the story as told by Millard, I too marveled at the gaping disparity between hers and the many Civil War depictions, and am happy that Mackowski tells “our side” of the story.

Thanks, Amanda. Millard’s book–which I really am enjoying tremendously–really does “need” Garfield to be heroic, and so she goes to great lengths to paint him as such. It’s a really romanticized version of Garfield, though.

Thanks for the Cozzens reference, which I hadn’t seen. Ackerman’s book, while exhaustive about events in the campaign, really avoids almost any kind of analysis of Garfield’s character at all. Perry spends considerable time on the topic because it sets Garfield apart from the other future-presidents in his book, although Perry’s portrait is mostly war-era and not Gilded Age-era Garfield.

A little dated in my reply, but a good biography also exists from Alan Peskin “Garfield” which deals well with the political and the military Garfield. I agree with you that Garfield was concerned with his election. Afterall, his campaign trip to New York to try and bring Roscoe Conkling and the Stalwarts on board would have fatal results in the long term. And he invented the Front Porch Campaign where groups came in on the train to his home in Mentor to meet and hear what the candidate had to say. It would have been interesting to have seen what kind of Presidency he would have had. His problems with Conkling were serious and unresolved at the time of his assassination. That said, Garfield was a very smart man. The Gilded Age may have taken another direction with him – instead of Arthur – at the helm.