“Life Given, Not Lost”: Captain Morey’s Final Charge—Conclusion

Authored by Edward Alexander

(part three of three)

Skirmishers in the 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery crept forward to pick off the cannoneers and horses, to prevent the withdrawal of the pieces, while the remainder of the Green Mountain Boys charged forward with the same instructions they received for the initial assaults that morning—to advance without firing. “The artillery fire was heavy and incessant,” remembered an anonymous Union soldier, “still our lines pressed on, obliquing to the left to gain Lee’s headquarters; still on through a swamp so deep that in many places our men sunk to their armpits, while canister and grape were shrieking their way over their heads.” Lieutenant John W. Yeargain’s Madison (Mississippi) Battery contested the Vermont Brigade’s final push up the ravine before the disabled guns were captured.

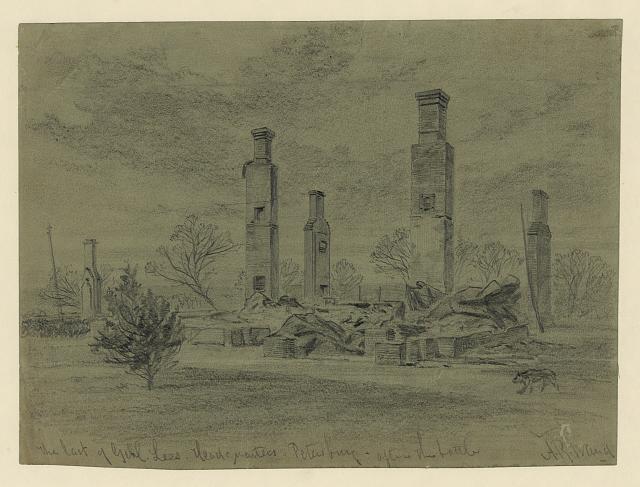

The last ditch efforts of Poague’s battalion bought time for Longstreet’s men to fill the void in the line, which ultimately would be abandoned that night as Robert E. Lee determined to begin his retreat west. “They had some strong Forts which our folks (I suppose) did not conclude to charge,” wrote Captain Walter W. Smith, 4th Vermont. “We threw up a line of works and lay there till day light… when our Yanks walked into Petersburg.” After nine and a half months, the Cockade City fell on April 3rd. Union troops north of the James River captured Richmond that same day. Amid the jubilant celebration, thoughts turned to the sacrifices necessary to deliver the two cities – “the price alike of victory and defeat.”

“While we were rejoicing at the good news of our successes,” remembered Private Fisk, “there was a tinge of anxiety to know who of our comrades were wounded, and who had fallen.” Captain Ephraim W. Harrington charged alongside Charles Morey as the two led their companies in the final assault against the Confederate artillery, and was able to deliver the tragic news to Reuben Morey of his son’s final moments:

He was killed in action near Petersburg yesterday after noon. I was by his side when he fell. he was killed by a Grape Shot. Striking him in the right shoulder and breaking it badly. he lived about twenty minutes after he was hit. I stayed with him untill he breathed his last. He never spoke after he was hit but he knew me about one minute. I closed his eyes and saw him carryed off the field by some of the men of his own company and they burryed him with as much respect as possable. There was a Chaplin with the men when he was burryed and he made a Prayer at his grave. He is burryed where he can easyly be found by any one if it is your wish to get his Body. his name written on a board and nailed on a Tree by his Head.

“It seems a hard fate to perish in the last struggle,” mourned Private Fisk, upon learning of Morey’s fate, “after having passed safely through so many.” Morey’s body remained in Virginia—reinterred in Poplar Grove National Cemetery—perhaps fitting for a soldier who found himself at home among his comrades. Captain Charles C. Morey rests beside 6,177 of the fellow Union soldiers he gave his all for, up through the final days of the war.

1 Response to “Life Given, Not Lost”: Captain Morey’s Final Charge—Conclusion