Paving Over Civil War Memory in the Sesquicentennial Season

A recent decision by legislators in Cattaraugus Country, New York, has paved the way for the destruction of the county’s Civil War Memorial and Historical Building.

A recent decision by legislators in Cattaraugus Country, New York, has paved the way for the destruction of the county’s Civil War Memorial and Historical Building.

Men from Cattaraugus County served in a number of regiments during the war, but arguably the best known was the 154th New York Infantry, better known as the Hardtack Regiment. Amos Humiston, the initially unidentified soldier at Gettysburg found with a photo of his three children, was from Cattaraugus County. The 188th New York came from the area, too; William Whitlock recounted their adventures through his letters in Allegany to Appomattox, edited by Valgene Dunham.

St. Bonaventure University, where I teach, is located in Cattaraugus County. So that’s my dog in the hunt. This is local, which makes it personal.

What follows is an open letter to the county legislators:

“What have you done for me lately?”

“What have you done for me lately?”

That seems to be the attitude of the Cattaraugus County Legislature, which has announced plans to demolish the Civil War Memorial and Historical Building that stands across from the county center in Little Valley—all in the name of convenient parking.

Ironically, “convenient parking” is not one of the motives most frequently cited by men 150 years ago when they chose to enlist as soldiers and sailors. They enlisted to preserve the Union, to abolish slavery, to fulfill their personal sense of honor and duty.

“I don’t care much where we go if it only helps the government to put down this cursed rebellion,” wrote Cpl. Thomas R. Aldrich of the 154th New York infantry regiment. “I would not give a snap to get out of this until our country is once more united in the bonds of peace and brotherly love. I came down here to protect the government in this her time of peril and I mean to stand by her to the last.”

Private Barzilla Merrill of the 154th said, “I came here because I thought that it was my duty to come and I expect to stand up like a man and do my duty like a man whatever that may be, and leave the event with God.”

Byron Brown of the 154th New York wanted to “break down the traitor’s form.”

But I’ve not seen a single instance where a man said, “Gosh, these Western New York winters are cold. People shouldn’t have to walk so far to do county business. Let’s fight for good parking!”

Because they enlisted, these soldiers and sailors endured years of privation, heartbreaking separation from their families, hard marching, and terrifying battle. They lost close friends. They gave up, quite literally, life and limb.

“I cannot tell how soon I shall be called upon to into a battle and if I do I may never come out alive,” wrote Second Lieut. John W. Badgero of the 154th, “and if I do not, you must remember your father died fighting for one of the best governments the sun ever shone upon.”

Badgero died of disease in June 1863, says the 154th’s regimental historian, Mark Dunkelman, who offered me a glimpse into the lives of these men. Aldrich was captured in northwest Georgia at the battle of Dug Gap, then endured a grueling imprisonment at Andersonville and elsewhere. Brown was discharged because of illness and a deformed foot. Barzilla Merrill and his son, Alva, were both killed at the battle of Chancellorsville. Imagine how Mrs. Merrill felt when she got that news.

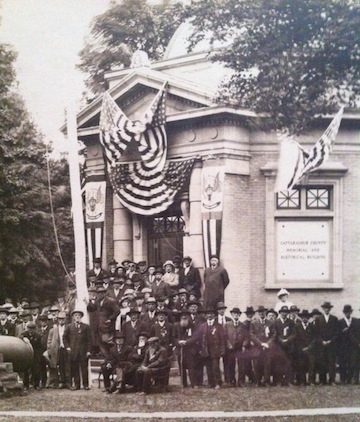

Rightfully so, the survivors wanted their sacrifices to be remembered. As veterans, they dedicated a memorial at the county seat on September 7, 1914, to much fanfare and with much public support. After all, they had done nothing less than help save the country. “One need only to observe the number of people who have assembled here to appreciate the fact that all of you consider this more than an ordinary occasion,” observed keynote speaker James Whipple at the dedication ceremony. “The day, the purpose for which you are here should and will be long remembered.”

Rightfully so, the survivors wanted their sacrifices to be remembered. As veterans, they dedicated a memorial at the county seat on September 7, 1914, to much fanfare and with much public support. After all, they had done nothing less than help save the country. “One need only to observe the number of people who have assembled here to appreciate the fact that all of you consider this more than an ordinary occasion,” observed keynote speaker James Whipple at the dedication ceremony. “The day, the purpose for which you are here should and will be long remembered.”

They entrusted that memory and the memory of their sacrifices to future generations.

To us, for example.

Now, the rest of the nation celebrates the 150th anniversary of the Civil War and remembers the sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of men just like our Cattaraugus County natives (not to mention the sacrifices of their families back home). Meanwhile, the Cattaraugus County Legislature has decided to recognize the memory of those men and the sacrifices they made by literally paving it over.

Those men who went off to war 150 years ago were no different than the men and women who, in more recent times, have gone off to serve in Afghanistan and Iraq. We would never dream of slapping those men and women in the face—yet to destroy the memorial in Little Valley would be much worse. The distance of time does not give legislators the right to insult those men who served 150 years ago. We do not get to discount their service just because it came generations ago. It is tantamount to saying, “Thanks—but what have you done for me lately?”

They. Saved. The. Country.

Legislators, what more did those men need to do to earn your respect?

————

My thanks to historian Mark Dunkelman, the regimental historian of the 154th NY, who helped me with the research on this piece. Mark has been working tirelessly to save this memorial. If you’d like to help, contact him at nyvi154th@aol.com.

If the men who fought that war are to be forgotten by the politicians…nothing is beneath them.

Disgraceful! The veterans of 1861-1865 gave their all and now the inheritors of this legacy want even more. Cattaraugus County legislators should be ashamed.

I came across this post while doing research on my ancestor, Barzilla Merrill. I hope to make it back East eventually to do more research. Thank you for honoring these soldiers.