The Bloody Railroad Cut at Gettysburg: Part Two

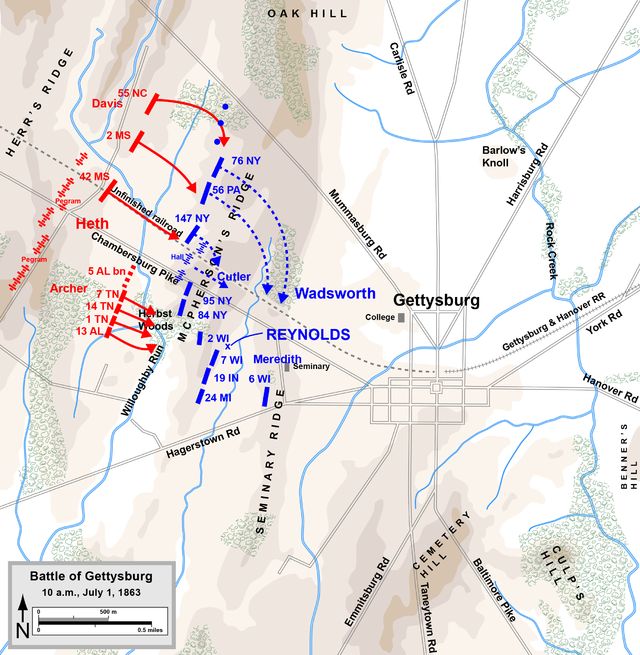

The Army of the Potomac benefited greatly early on July 1st due to the fact that no high ranking Confederate officer seemed to want to take control of the fight. Division commander Henry Heth has started the battle of Gettysburg, which was growing from a minor skirmisher to a pitched battle, something Robert E. Lee wanted to avoid until his Army of Northern Virginia was fully concentrated. Heth had committed only two brigades and a battalion of artillery at this point, and could have actually avoided a pitched battle if he had thrown forward the balance of his division, which would have driven Doubleday off of McPherson Ridge and back into the town.

Heth’s immediate superior, A.P. Hill, was nearly 5 miles away, as was becoming the norm, sick and lying on a cot at the Cashtown Inn. Lee and his second-in-command James Longstreet were still making their way to Cashtown, along a road that was quickly bottlenecking with traffic due to the fighting up ahead.

Yet with no true head on the snake of command this day, Henry Heth had nearly blundered to victory. All that would soon change.

Joe Davis’s brigade had had their way with half of Cutler’s brigade, they had driven off Hall’s Battery, who fought “for dear life,” and now had wheeled to the right so that they brigade was facing south. The butternut soldiers then decided the best way to defeat the enemy was to dive into the cut itself and use it as a readymade trench, ala Second Manassas. In theory this was a great idea, in practice though it was to be a disaster. “Our men thought [it] would prove a good breastwork but it [the side of the cut] was too steep…”

The 42nd and 2nd Mississippi dove into the cut, while the bulk of the 55th North Carolina remained out of, and on the north side of the cut. Still, elements of all three units intermingled in the cut, unit cohesion was gone, and all three of Davis’s regimental commanders were casualties. “…in changing front the men were all tangled and confused.” recalled one sergeant. Thinking that discretion was the better part of valor, Davis, who was not actually at the front, ordered his disorganized hoard off the field and back to Herr Ridge, but it was too late. Doubleday had seized the opportunity and pounced, turning the hunter into the hunted.

*****

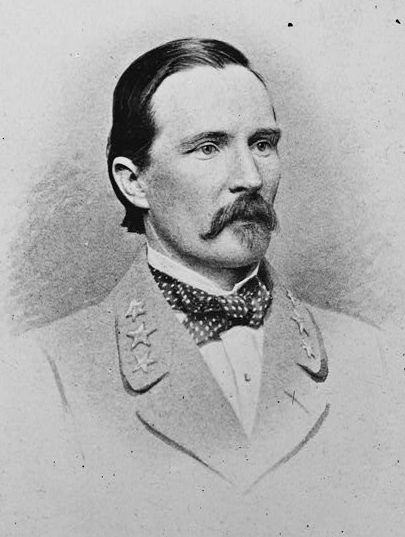

“Go like hell!” was the order received by Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Dawes. The young officer, just three days shy of his twenty-fifth birthday was called upon to right the ship for the Federal 1st Corps. Dawes and the 442 men of the 6th Wisconsin were the only reserves that Doubleday had on hand.

Rufus Dawes was the great-grandson of Revolutionary War hero William Dawes, the man who also made the midnight ride with Paul Revere. The Marietta College alum was an Ohio native, even though he commanded the 6th Wisconsin, and was the epitome of a citizen-soldier.

Dawes and his 6th Wisconsin had been halted before they could cross the swale from Seminary Ridge to Herbst Woods, and participate in the fighting with the balance of the Iron Brigade there. For a few minutes the 6th hung back near the Fairfield Road, but moments later the order came directing them to assist Cutler’s force north of the macadamized Chambersburg Pike. By this time Doubleday was in control of the field and was not missing a beat. Dawes set his regiment in motion “by the right flank [at the] double-quick toward the point indicated.”

On July 1st the 6th Wisconsin was an over-sized regiment. Attached to the command were 2 officers and 100 enlisted men which consisted of the brigade guard. The brigade guard was made up of 20 men from each regiment of the Iron Brigade, who could be used for various fatigue duties. Dawes split the guard in two, placing one company and one office on each of his flanks.

Half way to their objective the Badgers shook out into a line of battle. Dawes, on horseback, led the men toward their objective. From his vantage point he made out Cutler’s men, “in full retreat.” Suddenly Dawes hit the earth; his horse was hit carrying the young officer to the ground. In an instant he popped up to his feet, his men met him with a cheer.

“The regiment halted at the fence along the Cashtown [Chambersburg] Turnpike, and I gave the order to fire. In the field, beyond the turnpike, a long irregular line of yelling Confederates could be seen running forward and firing, and our troops were running back in disorder. The fire of our carefully aimed muskets, resting on the fence rails, striking their flank, checked the rebels in their headlong advance.”

To keep up a steady stream of fire Dawes ordered the men to “fire by file.” Any Rebels that were still in pursuit of Cutler’s three regiments north of the cut, now turned to meet the new threat and dove in the “earthwork” in front of them. Up to this point Dawes, “was not aware of the existence of a railroad cut.”

Major John Blair of the 2nd Mississippi said the rebels in the cut “were jumbled together without regiment or company.” The two sides had reached an impasse.

As the two sides blazed away at each other, Dawes decided to take matters into his own hands. He ordered the 6th over the fence and at the enemy, which, at about this time, received orders from Joe Davis to pull back to the Confederate line on Herr Ridge.

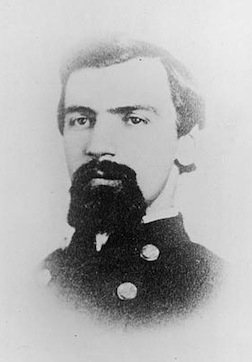

On the Badgers left arrived two more Federal units. The 95th New York had changed front to face from Herr Ridge, to face Davis’s men to their right rear in the cut. Dawes spotted their commander Major Edward Pye, and declared “Let’s go for them Major.” Pye ordered his regiment to guide on the Badgers. On the left of the New Yorkers came up the 84th New York (also known as the 14th Brooklyn), this make shift brigade made for the cut. Foot by foot the Federals pressed forward. On the south side lip of the cut stood the colors of the 2nd Mississippi. Their color bearer, William Murphy planted the flag in front of the cut to taunt the Yankees. Federals rushed for the flag. Lieutenant William Remington of the 6th Wisconsin went for the rebel colors. He was hit twice in the effort, he later lamented “I crawled forward, got up, walked backward until I got through our regiment, spoke to Major [John F.] Hauser, got damned for going after the flag and started for the rear on my best run. Flag taking was pretty well knocked out of me.”

Other groups of men went for Murphy’s flag, and like Remington, paid dearly for their efforts. . Then Ohio native Corporal Francis A. Waller stepped to the fore and went for Sgt. Murphy’s battle flag. “…a large man made a rush for me and the flag.” recalled Sgt. Murphy. “As I tore the flag from the staff he took hold of me and the color.” Waller and Murphy struggled for a moment, Waller’s brother Sam knocked away a Rebel musket meant for his brother Frank. Finally, the Yankee corporal came out with the flag, “threw it down and loaded and fired twice [while] standing on it. While standing on it there was a 14th Brooklyn [84th NY.] man took hold of it and tried to get it, and I had threatened to shoot him before he would stop.” Waller eventually gave the flag to Colonel Dawes, who took it and tied it around the waist of Sgt. William Evans. Evans was wounded and hobbled to the rear using two rifles as crutches. Evans made it to the Jacob Hollinger’s home on the east side of town where he initially received care. When the town fell to the Confederates, Evans hid the flag in the mattress he was laying on. Evans survived his Gettysburg wound and returned the flag to Dawes, who forwarded it on to General Meade as prize of battle. For his actions in seizing the flag Cpl. Francis A. Waller was awarded the Medal of Honor.

After Frank Waller captured the flag of the 2nd Mississippi, Dawes trumped his corporal. The Federals sealed off the second cut with one cannon of Roder’s section of John Calef’s horse artillery battery, Dawes’s adjutant swung a detachment of 20 men into the cut, in an attempt to cut off that line of retreat. Dawes wrote,

“…we were immediately upon the enemy, [there] was a general cry from our men of : ‘Throw down your muskets. Down with your muskets.’ Running quickly forward through the line of men, I found myself face to face with at least a thousand rebels, who I looked down upon in the railroad cut, which was here about four feet deep. Adjutant Brooks, equal to the emergency, had quickly placed men across the cut in position to fire through it…I shouted: “where is the colonel of the regiment?’ An officer in gray, with stars on his collar, who stood among the men in the cut, said: ‘Who are you?’ I said: ‘I am commander of this regiment. Surrender, or I will fire on you.’ The officer replied not a word, but promptly handed me his sword, and all his men, who still held them, threw down their muskets…”

Dawes captured 7 officers and 225 enlisted men from Davis’s brigade, including Major John Blair of the 2nd Mississippi, the man who turned his sword over to Dawes.

The assault on the railroad cut had been costly for the 6th Wisconsin as well. The Badgers lost 165 men in their short fight. Most of the casualties came during the advance from the Chambersburg Pike to the cut.

Dawes recalled one of his soldiers that fell in the charge. “Our bravest and best are cold in the ground or suffering on beds of anguish. One young man, Corporal James Kelley of Company B, shot through the breast came staggering up to me before he fell and, opening his shirt, to show the wound said, Colonel, won’t you write to my folks that I died a soldier?”

Near 11 A.M. the fighting along McPherson Ridge petered out. For now the battlefield at Gettysburg lay in Federal hands, but more fighting was on the way. More Rebels would arrive to the north, north-east, and west of town. Doubleday’s corps, though reinforced by more Federals sat in a precarious position. By 3:30 P.M. the Federal 1st and 11th Corps were sent streaming back through town, towards Cemetery Hill, with Confederates hot on their trail. Although the 1st Day at Gettysburg was a resounding Confederate success, those precious hours, bought so dearly on that Wednesday morning, gave the Federals time to concentrate at the small Pennsylvania town, and bring home a desperately needed victory over Lee.

Be sure to check out Fight Like the Devil: The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863; authored by Chris Mackowski, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis.

1 Response to The Bloody Railroad Cut at Gettysburg: Part Two