Sailors, Slaves, and Henry P. Moore

While doing some research for an upcoming post, I came across several photographs by Henry P. Moore, a New Hampshire artist who traveled to South Carolina in 1862.

Like many of his colleagues, Moore capitalized on the outbreak of the war, setting up make-shift studios for soldiers to send likenesses back home, as well as photographing specific scenes and moments in time. Although not as famous as Matthew Brady or Alexander Gardner, whose names conjure images of battlefields littered with fallen soldiers, or of dignified looking generals, Henry Moore’s photographs capture two under-represented social classes in Civil War history: soldiers and slaves.

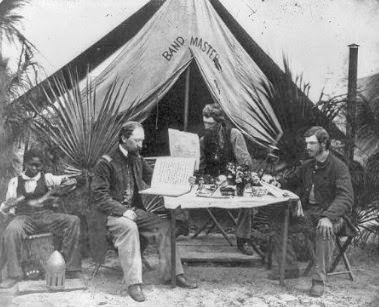

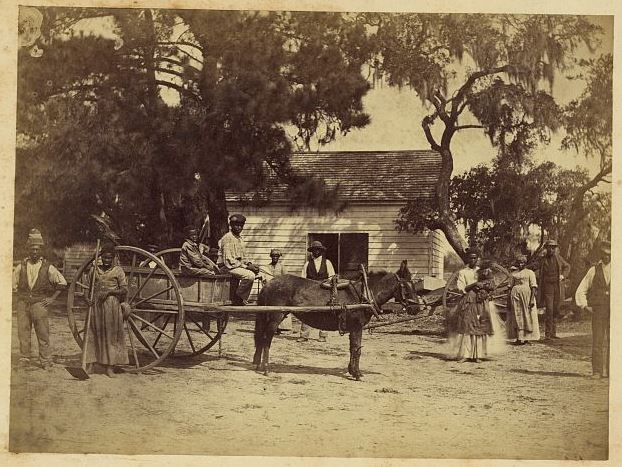

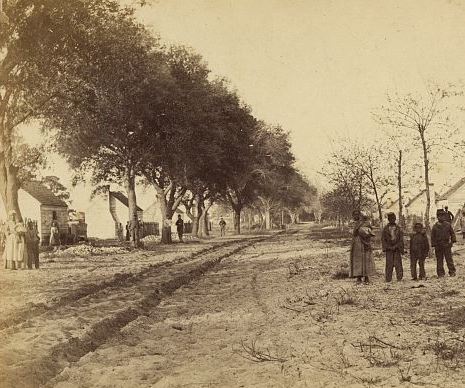

Moore, who ventured to Hilton Head, South Carolina to photograph the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment in 1862, began his early career as a landscape lithographer. His artistic background transformed his images into historical records of the people and places in South Carolina. Moore sought inspiration in the sites and the people around him, photographing plantation architecture, African Americans at work, and Union soldiers and sailors passing the time.

When Moore arrived in Hilton Head in 1862, the Battle of Port Royal had just taken place. Knowing defeat was evident, the Confederate army, along with citizens of Port Royal and the surrounding islands, fled inland, abandoning plantations, personal belongings, and around 10,000 slaves.

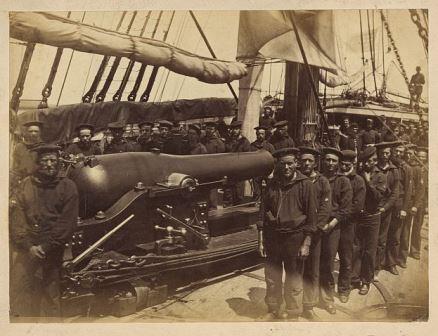

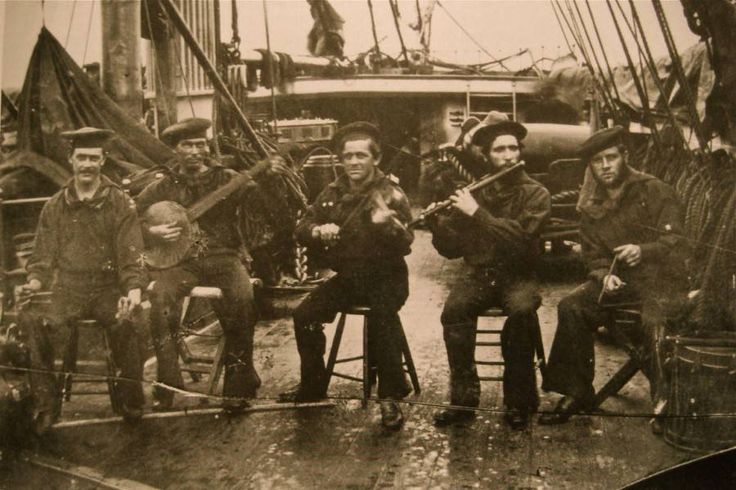

Union sailors and soldiers occupied the ports, continued the blockade, and maintained the Union presence in the Confederacy. Moore captures the lighthearted spirit of the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment, creating sets with all of the soldiers’ belongings pushed to the foreground of the image, showing the soldiers playing cards, reading books, and leisurely passing the time. Moore did the same with the sailors. While it was a little bit harder to accomplish this when photographing on a ship, Moore still brought a sense of leisure to the decks of the USS Wabash.

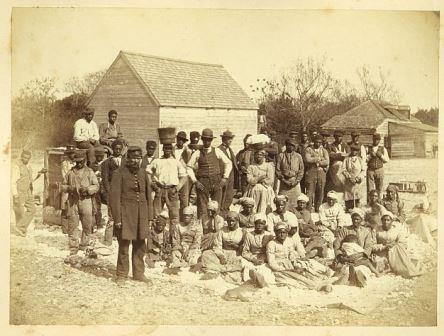

One of Moore’s most well known photographs is of several contraband sailors on the USS Vermont. While it doesn’t show the lightheartedness of the Wabash minstrels, Moore captures the resolve of the African Americans-their faces are set in grim determination, hoping to help the Union persevere over the Confederacy and end slavery.

The most unique items about Henry Moore’s photographs are the context under which the photographs were taken. This is especially true for all of his photographs of African Americans living and working in the Sea Islands. Because the Confederate army and the citizens of Port Royal fled the area and abandoned their property and slaves, the Federal government seized the land and the crops, as well as utilized the ready made labor force to supply the Union with much needed cotton for uniforms. This abandonment made all of the African Americans in the area contraband, the Sea Islands became a testing ground for reintegrating African Americans into free society. Moore’s photographs show these African Americans in a limbo state – not quite slaves, but not quite free either. With the master-slave relationship severed in the Sea Islands, and the Emancipation Proclamation not yet in affect, the uncertainty of their status is illustrated throughout their faces. They continue their work of sorting cotton and planting sweet potatoes. They stand in front of their homes and in the fields-congregating, conversing, and working together to create a different life outside the confines of slavery.

Perhaps Moore didn’t know or understand the significance of these photographs at the time, but he left a compelling body of work which are haunting, lighthearted, and informative all at the same time.

Reblogged this on waynewnri.