Mexican-American War 170th: Battle of Churubusco

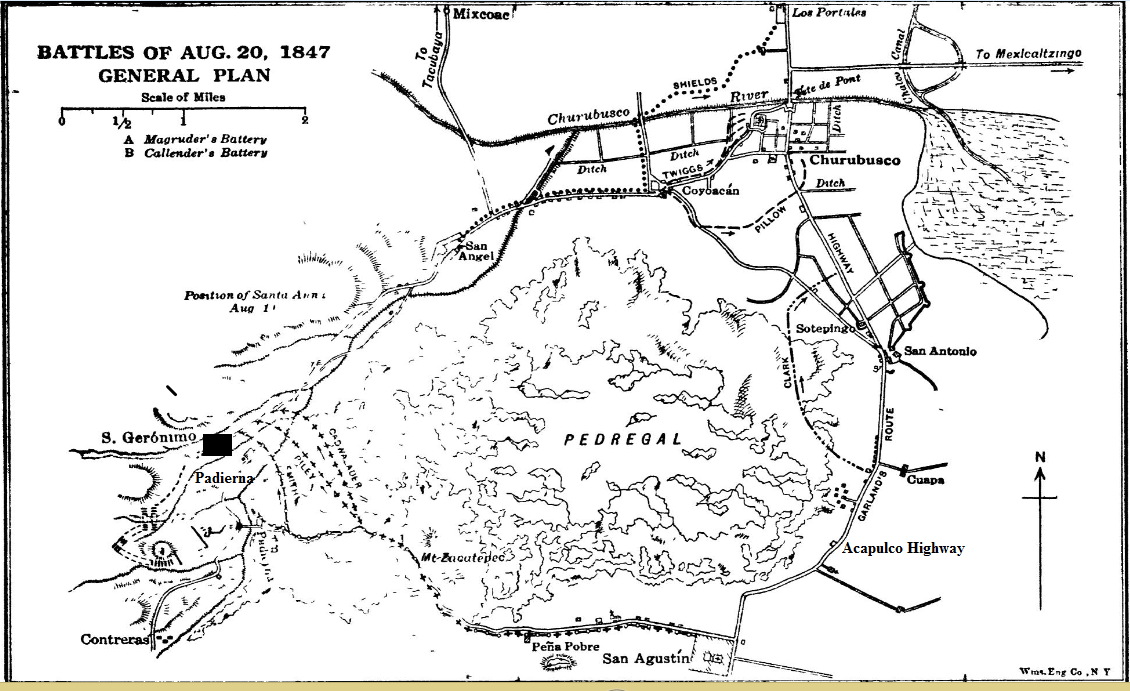

Following his victory at Contreras/Padierna on the morning of August 20, 1847, General Winfield Scott looked to keep pressing towards Mexico City. By mid-morning, Scott had his divisions headed north towards the Churubusco River. Whereas the victory earlier that morning had been quick and decisive, the ensuing engagement at Churubusco would be a “terrific battle.”[1]

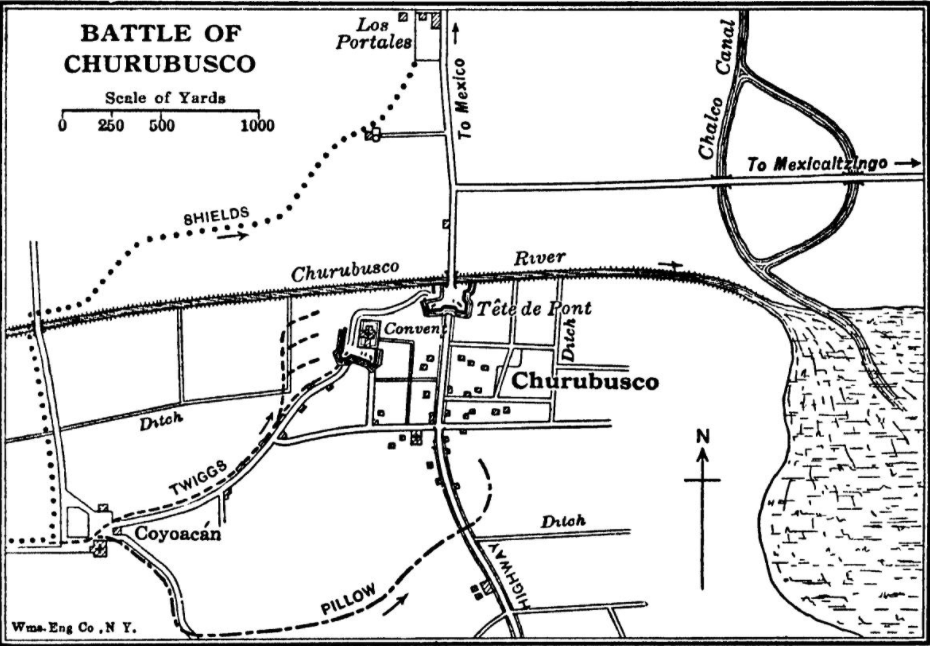

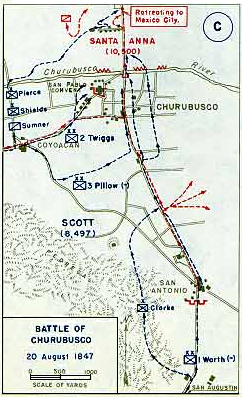

About five miles north of Padierna lay the village of Churubusco, bearing the same name as the river on its northern fringe, described as “more a mill stream or a canal than a river.”[2] Though not very wide, the river still needed a bridge to cross, and the Mexicans had built strong defenses to cover the bridge, called a tete-de-pont, or bridgehead. As Mexican forces retreated from their defeat at Padierna, they crossed the bridge and continued to head to Mexico City, about five miles away. To cover his army’s withdrawal, Santa Anna detached three regiments of infantry to defend the bridge and another 1,800 men to defend a nearby convent. Built in 1678, the Franciscan convent had walls that were twelve feet high and four feet thick. Pouring into the convent, Mexican forces quickly made a fort out of it, reinforced with seven pieces of artillery.[3] There were about 300 yards between the bridge and the convent, allowing the forces to lend mutual assistance when the Americans came attacking. Once his troops were set, Santa Anna continued onto Mexico City, thinking of Churubusco, as one historian described, “a mere delaying operation.”[4]

Santa Anna had, at least partially, mentally recovered from the setback at Contreras/Padierna. Throughout the whole campaign Scott’s army had, time and time again, outflanked and pushed back the Mexican defenders. Here, then, Santa Anna had men dug in and ready to fight. And Winfield Scott, overwhelmed by the victory that morning, marched his men straight towards the village. Scott “acted hastily,” one historian writes. “For once careless of the need for reconnaissance, he ordered an all-out attack” against the convent and the bridge. Another historian agrees, calling the preliminary scouting around Churubusco a “superficial investigation by engineers.”[5]

With his quick planning, Scott had an extremely straight-forward idea for the battle. Having outflanked Mexican positions at San Antonio that morning, William Worth’s division would march down the Acapulco Highway and hit the bridgehead. David Twiggs and Gideon Pillow would come down the highway leading from San Angel and would strike the convent. For all intents and purposes, Churubusco would be a “mopping-up operation” for Scott’s forces.[6]

(Justin H. Smith, “The War With Mexico” Vol. II), published 1919

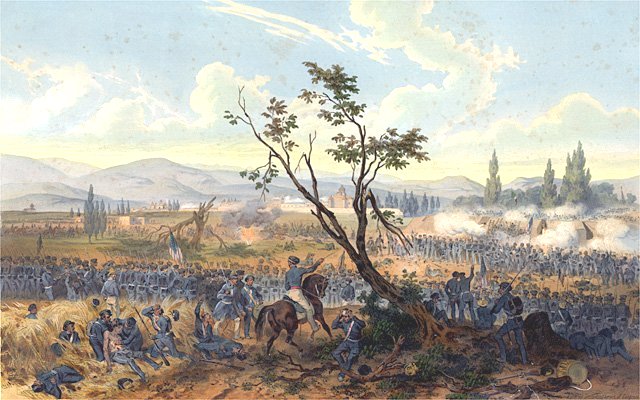

The Americans closed on the village around 12:45 p.m. and, in the words of E.A. Hitchcock on Scott’s staff, “a tremendous fight came off.”[7] Fighting began around the convent as Pillow’s and Twiggs’s men advanced against the thick walls. The heavy musketry surprised the Americans, with one officer writing, “Such showers of lead & iron I have never before heard.”[8] To escape the heavy fire, the American units left the road and dashed into oversized cornfields. While the corn provided some cover, it also made commanding the units increasingly more difficult.

Having stopped the first American sorties against the convent, some Mexican units got over-eager and tried to attack into the cornfields. The American infantry beat them back, and the sides settled into volleying back and forth, as the Mexican cannon around the convent scythed the fields with grapeshot.

William Worth’s men came up from San Antonio and soon dove into the battle. His soldiers led the attack against the bridgehead, which erupted in both musketry and artillery. One of Worth’s regiments, the 6th U.S. Infantry, “recoiled under the sweeping stroke of the artillery. . . The awful storm of lead and iron that poured down and across that causeway permitted no living thing to stand against it.”[9] Serving in the 6th, 23-year old Winfield Scott Hancock later wrote to his father, “It has been the theatre of a sanguinary battle.”[10]

More American units came onto the field, and, for one of the only times in his career, Winfield Scott seems to have lost control of the situation. He had thrown his available brigades forward, and once engaged, they devolved into smaller tactical actions with little direction from on-high. Fortunately for Scott, his younger officers shone on the afternoon of August 20, 1847. The men who would command thousands of soldiers on fields from Virginia to Tennessee in fifteen years instead commanded platoons and companies. Captain Joseph Hooker, for example, helped guide a regiment of Voltigeurs, commanded by Lt. Col. Joseph E. Johnston, through the corn and against the convent.[11]

Fighting continued to see-saw. Lieutenant Don Carlos Buell of the 3rd U.S. Infantry went down in front of the convent with a chest wound– he would recover and command the Army of the Ohio in 1862. Captain Robert Anderson (of Ft. Sumter fame) fought with the 3rd U.S. Artillery against what he described at the time as “the strongest field of fortification I ever saw.”[12]

The battle changed in favor of the Americans when the bridgehead fell. Picking up where other units had stopped, the 8th U.S. Infantry charged the tete-de-pont. Attacking across a canal in front of the bridge, the Americans lacked ladders so clawed themselves out, including Lt. George Pickett, who had graduated dead last in 1846. By beating the Mexicans back and placing their colors on the bridgehead, (specifically Lt. James Longstreet, who proudly stabbed the standard of the 8th U.S. into the soil), the Americans could now encircle the convent and also turn captured Mexican artillery against the walls.[13]

Blasting the convent with the Mexican cannon as well as their own artillery, the Americans made a final plunge against the convent. Inside the walls, fighting was hand-to-hand, and seemed to keep going. And the Americans soon found out why. Helping to defend the convent’s walls were the San Patricios.

This Mexican unit actually consisted of former American soldiers, mostly Irishmen, who had deserted in the face of anti-Irish sentiments in the old army, and wary of fighting a fellow Catholic nation. The San Patricios had made a name for themselves, fighting from Monterrey, Buena Vista, and Cerro Gordo. Knowing that defeat and capture meant almost certain death for desertion, the San Patricios kept fighting, tearing down the white flag of surrender that other Mexican troops tried to fly. Finally they were subdued.[14]

While the fighting at the convent and the bridgehead ended, there was one final postscript for August 20. Flushed with success, American soldiers pursued their defeated foes across the Churubusco River and towards Mexico City. After about two miles Winfield Scott ordered his men to stop, but some soldiers ignored the order. The 1st U.S. Dragoons kept riding down prisoners, almost riding straight towards the gates of Mexico City. At the head of Company F rode Capt. Philip Kearny, who continued to flash his saber. Fending off the attack, Mexican artillery opened fire, shattering Kearny’s left arm. The repulse of the dragoons marked the denouement for Churubusco.[15]

For being little more than a mop-up for Contreras, Scott’s men paid a heavy price. Some 133 Americans had been killed, and another 865 wounded, making Churubusco one of the bloodiest battles of the entire war. But as an exchange for that, the dual actions at Padierna and Churubusco had cost Santa Anna a full third of his army.[16]

In the wake of August 20, 1847, the armies again separated. Santa Anna retreated into the confines of Mexico City and Winfield Scott once more turned to his attached diplomat, Nicholas Trist, to see if a peace could be worked out. In time those talks would fail.

So the war would continue.

_____________________________________________________________

[1] Daniel Harvey Hill, A Fighter from Way Back: The Mexican War Diary of Lt. Daniel Harvey Hill, 4th Artillery, USA, ed. Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and Timothy D. Johnson (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2002), 113.

[2] Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. I. (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 268.

[3] Justin Smith, The War with Mexico, Vol. II, (New York: MacMillan, 1919), 110-111; Timothy D. Johnson, A Gallant Little Army: The Mexico City Campaign (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 179-180.

[4] John S.D. Eisenhower, Agent of Destiny: The Life and Times of General Winfield Scott (New York: The Free Press, 1997), 282.

[5] K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974), 297.

[6] Eisenhower, 282.

[7] Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Fifty Years in Camp and Field: Diary of Major General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, U.S.A. Edited by W.A. Croffut. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), 278.

[8] John Wilkins quoted in Johnson, 188.

[9] Frederick E. Goodrich, The Life of Winfield Scott Hancock, (Boston: B.B. Russell, 1886), 56.

[10] David M. Jordan, Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1988), 16.

[11] Jack K. Ballard, “General Joseph Hooker: A New Biography,” Doctoral Thesis, Kent State University, 1994, 46-47.

[12] Robert Anderson, An Artillery Officer in the Mexican War: 1846-7 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1911), 295.

[13] Lesley J. Gordon, General George E. Pickett in Life & Legend (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 24.

[14] Paul Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict during the Mexican-American War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 107.

[15] Johnson, 190.

[16] Bauer, 300-301.

This narrative is very helpful while watching the battle’s dramatizations in the North and South (1985) mini series (Patrick Swayze) as well as One Man’s Hero (1999) film (Tom Berenger).

By agreeing to a truce, do you believe Scott made the same mistake as Taylor at Monterrey?

– Will

Thanks for commenting, Will. Definitely had those scenes in mind when I was writing.

I certainly think the repeated truces that Taylor/Scott agreed to were mistakes. They were under the cover of trying to sue for peace, but Santa Anna and other Mexican commanders always used that time to prepare themselves for the next action, or pocketed bribes they extorted under the auspices of furthering peace talks.

But I will say that when Scott got word of the truce being broken, he very quickly planned his next offensive, as we’ll see in just a couple of weeks. Taylor’s truce went on for months; Scott was quick to action.

Hello. Did some of the Mexican soldiers suffered from “friendly fire” during the battle?