Struck by a Fired Ramrod, Part 1: Delayed Mortal Wounding at Spotsylvania’s Bloody Angle

“This has been a Sabbath to me,” confessed Surgeon George T. Stevens to his wife, Harriet, in a letter written Thursday evening, August 4, 1864. “No day since the campaign commenced last May has seemed like Sabbath before, but this has been more than usually a day of rest and a day of solemnity with us.”[1]

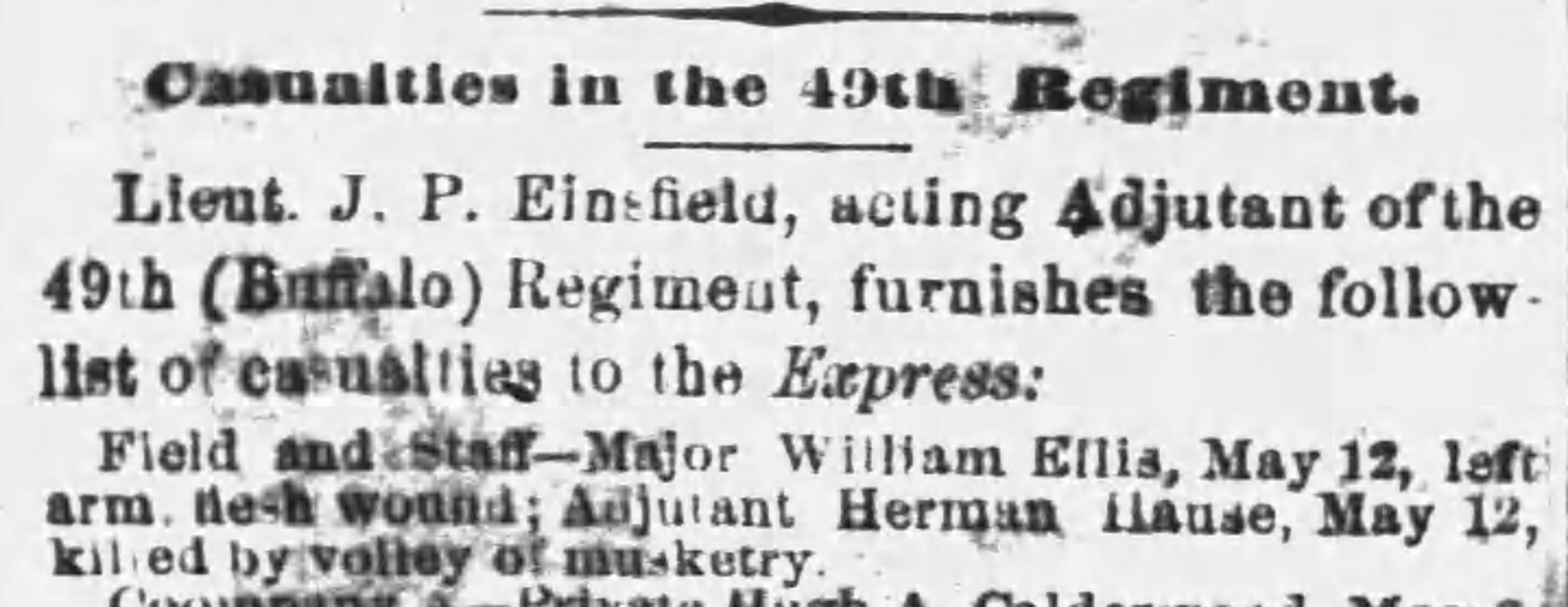

Stevens, serving with the 77th New York Infantry of the VI Corps, was camped in Maryland at the time. The unit had been sent there in response to Jubal Early’s offensive that culminated in Confederate repulse at Fort Stevens. The Union soldiers now enjoyed their bloodless respite away from an Army of the Potomac that had been locked in continual combat from the Wilderness to Petersburg. Tragedy managed to still strike along the Monocacy River valley, repercussions from a unique wound sustained nearly three months earlier at the Bloody Angle. Major William Ellis, a friend of the New York surgeon, had been found dead in his tent from no noticeable cause.

William Ellis was born on July 17, 1842 in Brantford, West Canada—present-day Ontario. His father, Alexander Ellis, died in 1854, leaving William to provide for his mother Catharine. The next year, at the age of fifteen, William enlisted into the “Prince of Wales” 100th Regiment and was soon promoted color sergeant in the 22nd Royal Regiment. When the Civil War broke out William bought his discharge from the British army and traveled to his mother’s home in Buffalo, New York. There he enlisted into the 49th New York Infantry in the summer of 1861.[2]

His previous military service warranted the nineteen year old a position as second lieutenant. Sergeant Alexander H. McKelvy recalled, “I do not know whether [Ellis] raised any men or not, but there was a camp rumor afloat among the men that he had taken some sort of leave from one of Her Majesty’s rifle regiments in Canada in order to see service in the war between the states.” The next year Ellis received promotions to captain in January and major in December. His experience and pompous attitude impressed his comrades. Surgeon Stevens referred to him as “the dashing, impetuous young fellow who used to ride his horse so furiously.”[3]

McKelvy commented on Ellis’s exploits inside and outside of the encampment, “It was his great delight to break loose from the monotonous round of camp life and go on a scouting trip beyond the lines in pursuit of adventure and pleasure, for it was rumored that he was not averse to the charms of the fair sex. He was always well mounted and… he rode a powerful black horse, fleet of foot, and able to extricate his dare evil master from any difficulty he might plunge into.”[4]

Ellis became a popular figure in camp. His various exploits inevitably produced frequent gossip. “It is said that Major Ellis who had just returned from a visit to Canada was also married in his absence,” wrote a member of the 49th in March 1863. Later testimony would suggest it was just a rumor.[5]

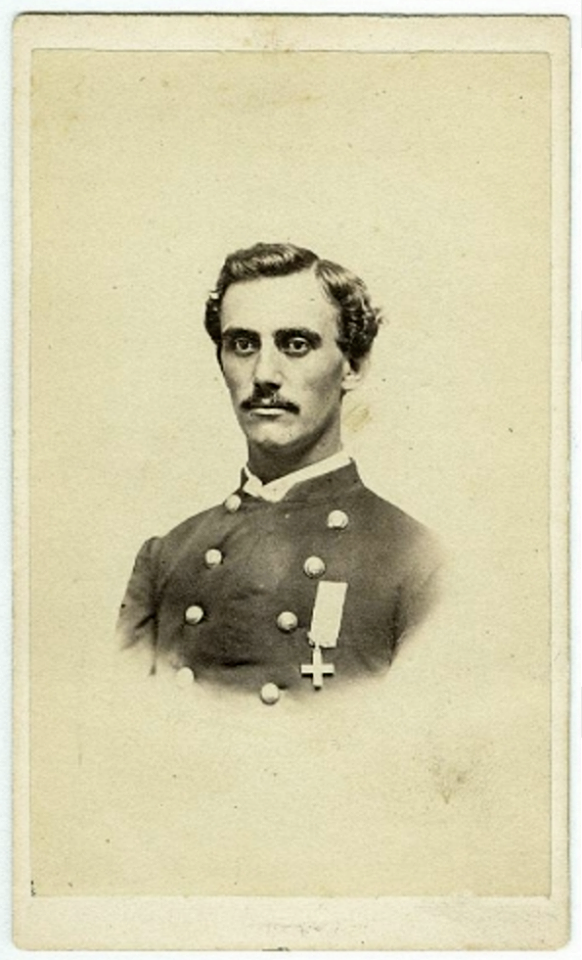

The major was certainly active on the courtship scene, however. Scott Valentine, a contributing editor of Military Images, profiled William Ellis in the magazine’s Spring 2014 issue. Valentine owns a carte-de-viste of Ellis, upon the reverse side of which the flirtatious major had signed, “I kiss your hand.”[6]

The New York major also won the approval of his commanders and fellow officers, serving at the head of the regiment several times when his superiors went on medical or personal furlough. A newspaper correspondent with the 49th claimed that Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, commanding the VI Corps, had declared shortly before his untimely death that Ellis “was the best fighting officer in his corps.” Massachusetts captain Mason Whiting Tyler also believed that Ellis “was one of the best officers in our corps.”[7]

Sedgwick’s death on May 9, 1864, and the Wilderness wounding of Brig. Gen. George Washington Getty, at the helm of the division to which the 49th belonged, stressed the VI Corps’ high command during the Overland campaign. Brigadier General Horatio Gouverneur Wright took over the corps, promoting Brig. Gen. David Allen Russell to lead his 1st Division. Brigadier General Thomas Hewson Neill also moved up to take command of Getty’s 2nd Division, leaving his 3rd Brigade under the leadership of Col. Daniel Davidson Bidwell, the original commander of the 49th New York. Lieutenant Colonel George Washington Johnson now led that unit.

During the infamous morning of May 12th, Bidwell sent his former regiment and the 77th New York Infantry to support Oliver Edwards’s brigade, who in turn had advanced to assist the II Corps as their determined assault against the Spotsylvania “mule-shoe salient” bogged down. Together the New York regiments hit the northwest face of the salient, just above where Col. Emory Upton had centered his attack two days before. Stephen Dodson Ramseur’s North Carolinians provided their immediate adversaries but Nathaniel Harris’s Mississippians and Abner Perrin’s Alabamians, reinforcements from A.P. Hill’s Confederate Third Corps, soon threw their weight into the combat. The New Yorkers clung to their position just outside of the Confederate earthworks, dubbed the “Bloody Angle.” Surgeon Stevens recalled after the war:

A breastwork of logs separated the combatants. Our men would reach over this partition and discharge their muskets in the face of the enemy, and in return would receive the fire of the rebels at the same close range. Finally, the men began to use their muskets as clubs and then rails were used. The men were willing thus to fight from behind the breastworks, but to rise up and attempt a charge in the face of an enemy so near at hand and so strong in numbers required unusual bravery. Yet they did charge and they drove the rebels back and held the angle themselves.[8]

Occasional charges and countercharges did little to break the locked stalemate. The Canadian major was wounded in an unusual manner at some point during this chaotic phase. Sergeant George Norton Galloway, of the 95th Pennsylvania Infantry, wrote that “during one of the several attempts to get the men to cross the works and drive off the enemy,” Ellis “excited our admiration” as he mounted the parapet in advance of the brigade, before he “was shot though the arm and body with a ramrod.”[9]

Sergeant Alexander H. McKelvy afterward recalled that Ellis was wounded “while leading the regiment in a daring charge on the enemy’s works. He was hit with one of the iron ramrods, used by the infantry in those days, which some excited Confederate had neglected to remove from his rifle barrel before firing. This rammer passed through the major’s left arm and bruised his chest severely.”[10]

The New Yorker’s gallant action before his wounding was noticed by the recently-promoted Brig. Gen. Emory Upton, who had already made a name for himself at Spotsylvania. Even though Ellis was not even part of his brigade, Upton singled him out as well as Maj. Henry P. Truefitt, 119th Pennsylvania, who was killed at the Bloody Angle, when writing the May 12th section of his Overland campaign report. Upton wrote that the pair, “by their gallant conduct excited the admiration of all… the country can ill afford to lose two such officers.”[11]

Ellis was evacuated to a hospital in Fredericksburg where Surgeon Stevens examined the injury and found the ramrod “passed through the left arm and then bruised the side near and a little below the heart.” The major “suffered fearfully from the effects of the bruise in the side,” and the surgeon afterward claimed, “I supposed at the time that his heart was injured.” Surgeon William Warren Potter, a friend of Ellis’s serving with the 57th New York Infantry, however, saw the major and noted that his wound “is not reported as dangerous.[12]

After being stabilized, Ellis was sent onward to Washington to continue his recuperation. Soon thereafter he received a thirty day furlough and returned to Buffalo to recover, arriving at the city on May 25th. “It is to be hoped that he will recover from his injuries while among friends,” the Buffalo Daily Courier expressed. “He is able to be about,” wrote the Buffalo Evening Post, “and anticipates a speedy cure.” Isaac A. Verplank, a prominent local judge, later testified that he hosted William at his home frequently during his medical leave and that the soldier’s painful wounds produced occasional spasms.[13]

Only partially recovered from his injury, Ellis departed from home on June 17th to rejoin his unit. In his absence the Army of the Potomac had fought from Spotsylvania to Petersburg, via the North Anna, Totopotomoy, and Cold Harbor. Rejoining the VI Corps, Ellis received assignment as inspector general on Brig. Gen. David A. Russell’s 1st Division staff. Hospital Steward John Newton Henry noted that Ellis returned earlier than the rest of the Overland campaign casualties, writing on the 29th, “None of our wounded officers have returned but Major Ellis.”[14]

Surgeon Stevens afterward wrote in August that Ellis’s change to a supposedly less taxing assignment nevertheless resulted in the officer performing “a great deal of labor as provost marshal and in many other capacities.”[15] He further elaborated after the war:

Returning to his command before he had fully recovered, he was advised by medical officers not to attempt any severe duty. But being detailed to the staff of General Russell, commanding the First division, he at once resumed active military duties. On these recent marches, the major, weary of inaction, had taken command of a body of men who acted as additional provost-guard to the division. In this position he had exhibited his usual energy, though it was thought by some he executed his duties with too great severity. Ever since receiving his wound, he had complained of severe neuralgic pain in the region of the heart.[16]

Other friends in the army, like William Potter, however noted at the beginning of July that Ellis “was, as usual, looking well.” A week later Potter visited the 49th New York and took supper with Bidwell. Ellis called on him while the surgeon was there and the two snuck away to view a carriage that Ellis has captured from either a local resident or Confederate wagon train and stashed away in the woods. While admiring the prize, orders came to Russell’s headquarters to prepare to leave for Maryland to repulse Jubal Early’s offensive. “Ellis was in great glee over the prospect, and flew around to make preparations for the transfer of the troops to their new field;” recalled Potter, “so I hastily bade him good-bye, but never saw him afterwards.”[17]

This is part one in a three-part series. The next two articles will appear tomorrow and Thursday.

[1] George T. Stevens to “My Darling Hattie,” August 4, 1864, Wiley Sword Collection, Pamplin Historical Park.

[2] John M. Priest, ed. Turn Them Out to Die Like a Mule: The Civil War Letters of John N. Henry, 49th New York, 1861-1865 (Leesburg, VA: Gauley Mount Press), 1995, 204.

[3] “Sergeant Alexander H. McKelvy’s Report of His Capture by the Confederates, September 17, 1863,” Frederick D. Bidwell, ed. History of the Forty-ninth New York Volunteers (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1916), 105. Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP.

[4] “Sergeant Alexander H. McKelvy’s Report of His Capture by the Confederates, September 17, 1863,” 105.

[5] John N. Henry to “My Dear Wife,” March 16, 1863, Priest, Turn Them Out to Die Like a Mule, 177-178.

[6] Scott Valentine, “A Conspicuous Target: Major William Ellis, 49th New York Infantry, at the Bloody Angle,” Military Images, Volume 32, Number 2 (Spring 2014), 52.

[7] “From the Forty-ninth Regiment,” Buffalo Daily Courier, May 17, 1864. Mason W. Tyler to parents, August 4, 1864, William S. Tyler, ed. Recollections of the Civil War with Many Original Diary Entries and Letters Written from the Sear of War, and with Annotated References (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 262.

[8] George T. Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps: A Concisce Narrative of Events in the Army of the Potomac, from from 1861 to the Close of the Rebellion, April, 1865 (Albany, NY: S.R. Gray, 1866), 334.

[9] G. Norton Galloway, “Hand-to-hand Fighting at Spotsylvania,” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Volume 34, Number 2 (New York: The Century Co., June 1887), 306.

[10] A.H. McKelvy, “Forty-ninth New York Volunteers,” New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga, ed. Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg, Volume 1 (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1902), 390.

[11] Emory Upton to Henry R. Dalton, September 1, 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Volume 36, Part 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891), 669.

[12] Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP. William W. Potter, “Three Years with the Army of the Potomac—A Personal Military History,” Buffalo Medical Journal, Volume 68, Number 1 (August, 1912), 15.

[13] “Personal,” Buffalo Daily Courier, May 27, 1864. “Home Again,” Buffalo Evening Post, May 26, 1864. Isaac A. Verplank, Statement, June 28, 1865, William Ellis Pension, Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Widows and Other Veterans of the Army and Navy Who Served Mainly in the Civil War and the War With Spain, compiled 1861-1934, Record Group 15, National Archives.

[14] John N. Henry to “My Dear Wife,” March 16, 1863, Priest, Turn Them Out to Die Like a Mule, 374.

[15] “Gone to the Front,” Buffalo Evening Post, June 23, 1864. Stevens, August 4, 1864, PHP.

[16] Stevens, Three Years in the Sixth Corps, 334.

[17] William W. Potter, “Three Years with the Army of the Potomac—A Personal Military History,” Buffalo Medical Journal, Volume 68, Number 2 (September, 1912), 83-84.

Interesting article ; have never before read of Ellis.

Nicely done Mr. Alexander!