Steve Earle, “Dixieland,” and the Irresistible Charm of Buster Kilrain

The myths of Gettysburg rear their heads in the most unexpected places.

The myths of Gettysburg rear their heads in the most unexpected places.

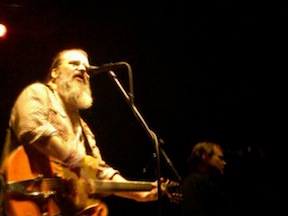

At a Steve Earle concert in Rochester, New York, a couple weeks ago, the folk-rocker launched into a pair of songs related to the Irish. Before he did, though, he launched into a history lesson—and lo and behold, who should suddenly appear in the story?

A lot of people who fought in the war, particularly for the North, were recent Irish immigrants, Earle told the audience. Because those recent arrivals weren’t necessarily invested in the idea of union, they had to be given other reasons to fight. So, for them, Earle said, the war was a class struggle.

“I love my job,” said Earle, well known for his left-leaning politics and support of the working class. “It’s amazing all the pinko bullshit I can slip into my songs.”

Then, like a whack-a-mole that pops out of its burrow, Buster Kilrain begins to sing “Dixieland.”

“I am Kilrain and I’m a fightin’ man and I come from County Clare,” the song’s narrator declares.

There’s no mistake that this is the same Buster Kilrain—the same fictitious Buster Kilrain—who appears in Michael Shaara’s Pultizer-winning novel The Killer Angels because the song’s narrator comes right out and says it: “I am Kilrain of the 20th Maine and we fight for Chamberlain.”

An odd choice, using the 20th Maine as a platform for singing about the Irish and class struggle, I thought. And an odd choice to use Buster Kilrain as the avatar of that story.

“Kilrain is English in origin, making it an insulting moniker for any true Irishman of the 1860s,” points out historian Tom Desjardin points out in his excellent book These Honored Dead: How the Story of Gettysburg Shaped American Memory. “Further, it is unlikely that there would have been a ‘Buster’ Kilrain in the 20th Maine, for the unavoidable reason that ‘Buster’ did not become a popular name until Buster Keaton became a famous movie actor fifty years after the Civil War.”

That hardly matters, though. In art, truth trumps fact—and Earle’s song sounds true.

As Desjardin points out, people continue to reshape the story of Gettysburg into images that satisfy their own needs. For Earle, that means reshaping Kilrain, the story of the Irish, and the battle of Gettysburg into a story of class struggle. “I damn all gentlemen/Whose only worth is their father’s name and the sweat of a workin’ man,” the song’s narrator says.

It’s hardly a wonder that Earle fell under Buster Kilrain’s charismatic spell. To this day, years after the novel was adapted into the movie Gettysburg, people still show up at the battlefield looking for Kilrain’s name on the 20th Maine’s monument.

“It does not seem to bother people that the character is a middle-aged, overweight private who follows his commanding officer around telling him what to do while calling him ‘darling,’” writes Desjardin. “Nor does it seem to register that the Kilrain to whom they refer is a Hollywood version of a character from a novel. The little Irish soldier is so endearing, they simply wish he were real and follow that instinct despite al the evidence to the contrary.”

Earle must’ve liked the character so much, in fact, that he chose to keep Kilrain alive. In the novel and film, Kilrain gets killed, but in the song, the Irishman appears to have survived—or he sings from beyond the grave. “When the smoke cleared out of Gettysburg, many a mother wept,” he sings from a post-battle point of view. “For many a good boy died there, sure, and the air smelled just like death.” That’s an after-the-battle perspective Shaara’s Kilrain didn’t have.

There’s no way to know if Earle knew his song’s protagonist was fictitious when he chose to write the song from Kilrain’s perspective, but it’s hardly important to Earle’s songwriting. While it frequently rankles historians when artists co-opt history—because facts are usually the first casualties—from the artist’s perspective, what matters is the emotional and intellectual impact of the work.

The irony here is that Earle isn’t even co-opting history; he’s co-opting other art to make art of his own. What matters to Earle, then—and to the majority of his fans—is whether he writes and performs an entertaining song and whether he makes the point he sets out to make:

The irony here is that Earle isn’t even co-opting history; he’s co-opting other art to make art of his own. What matters to Earle, then—and to the majority of his fans—is whether he writes and performs an entertaining song and whether he makes the point he sets out to make:

Well we come from the farms and the city streets and a hundred foreign lands.

And we spilled our blood in the battle’s heat

Now we’re all Americans.

Buster Kilrain, I suspect, would approve.

It’s very dangerous to only look at economics or class struggles, when trying to understand history. We know for a fact that people do things that are not in their economic interest all the time, today and in the past. Reasons why people fight for one side or another are very complicated.

Indeed, and trying to boil those reasons down into a song, or a song intro, can lend itself to oversimplification. But I appreciate that such avenues of expression also do a good job of raising awareness.

Earle knew Kilrain was fictitious, and knew, in fact, that he was a composite of three individuals in the 20 Maine (he says, two of whom died at Gettysburg and one who did not).

I’ve seen Earle in concert a few times, and once at a book reading. He usually prefaces his Civil War songs with a little talk about the war, and on at least two occasions I’ve heard him openly scoff at the neo-Confederate notion that slavery was not at the heart of the sectional rift. I linked to one of Earle’s song introductions about the Civil War here, in which he specifically addresses Shaara’s Kilrain character: http://tinyurl.com/3u2jq5u

For me, Earle’s best Civil War-themed song — far and away — is Ben McCulloch. It’s cool because it tackles events in the Trans-Mississippi, and because it gives a alternate, less gratuitously heroic perspective of the Confederate foot soldier. I blogged about that song as well, and linked to a video rendition. Please pardon the self-promotion here: http://tinyurl.com/3cchpvf

Earle is a great favorite of mine. Thanks for contributing this thoughtful piece about him and his music.

Thanks for taking the time to flesh out the story, David. And no worries about “self-promotion”–we appreciate thoughtful contributions.

A simple google search or you know any research at all would’ve “fleshed out the story” before you took the time to write a blog with an obvious axe to grind. I feel like the whole point of the article is to discredit Earle.

Actually, Billy Yank, I have been a huge Steve Earle fan since “Guitar Town.” The whole part of the article was to muse on the relationship between history and art (something I do a lot of here) and fact and truth.

I don’t know anything about Tom Desjardin, but the idea that by the mid 1800s there weren’t at least tens of thousands of Irish (both Catholic and Protestant) with English names shows total ignorance of history. Probably not many Kilrains (there still aren’t many), but I’d be very surprised if there weren’t any.

As David says, Earle is usually pretty careful when he introduces the song to say Kilrain is fictitious and that he was inspired by Shaara’s book (not the movie, by the way). In fact, I have heard him say Shaara is one of his favorite authors.

And I think, though you were sarcastic, that truth DOES trump fact in art. We need to be careful about teaching the difference between history and historical fiction (in novels, films or in other forms of art), but art and fiction can draw people in and express a kind of truth about what it might have been like to live in a particular time and place. The real problem is historiography, and that goes for historical “fact” as much as historical fiction. If you take one source, whether artistic interpretation or dry academic history, and assume that it is the Truth with a capital T, you are going to end up with an weak understanding of the complexity of history.