Now the Drum of War—Part Four

Final part in a series

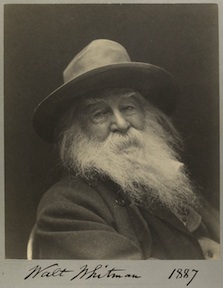

We conclude Rob Couteau’s interview with Robert Roper, author of the new book Now the Drum of War: Walt Whitman and His Brothers in the Civil War.

In today’s installment, the writers talk about the international impact of Whitman’s writing, and Roper wraps up the story of the Whitman family.

ROB COUTEAU: One often hears about Walt Whitman’s influence on American poets, but it was really a worldwide influence.

ROBERT ROPER: Yeah. So many people read him and – wow – it changed their lives. It was so hopeful, to hear him speak frankly about his sexual life. But that whole tone: it’s a modern tone. I never heard it before him.

RC: It’s completely unique. Here’s an example of this worldwide influence. In a letter to his sister from 1888, Vincent Van Gogh writes of Walt: “He sees in the future, and even in the present, a world of healthy, carnal love, strong and frank – of friendship – of work – under the great starlit vault of heaven a something which after all one can only call God – and eternity in its place above this world. At first it makes you smile, it is all so candid and pure; but it sets you thinking for the same reason.”

RR: Gosh, what an incredibly astute characterization! And that he got so much of Walt in a few phrases. I particularly like where he says, “At first it makes you smile, it is all so candid and pure.” Whitman’s forthright approach to all the big questions seems naive, at first, and braves a kind of ridicule. But who else can put it all together the way he does? Van Gogh hits the mark.

RC: When I interviewed Hubert Selby, he brought up a wonderful point about growing up in Brooklyn. He said there’s a music of language in the street that you just don’t have in other places. You know, this marvelous, musical way of speaking: the argot, the slang, the mixture of immigrants and so on. I wonder if this had something to do with Whitman’s unique use of a vernacular tone.

RR: Yeah, he’s real frank about that. He loved the density of New York and Brooklyn – the variety of folks – and he rejoiced in slang. That’s a part of why he hung out with cart drivers and stage drivers – the equivalent of bus drivers – who had this argot. Yeah, he loved that. Was it more intense in Brooklyn and New York than anywhere else? Well, probably, because it was so densely populated.

I read Last Exit to Brooklyn when I was a college student. It just knocked me and all of my friends over. Wow.

RC: I enjoyed the way you brought the Whitman saga to its somewhat tragic conclusion. By “moving to the country, George fulfilled an old dream of the family’s … Once the Whitman’s had been Long Island gentry … now, wealthy with the earnings of a modern economy, George returned to the land.” But George’s wife died without leaving any children behind, although Walt’s brother Jeff was survived by his daughter, Jessie Louisa. Perhaps you could talk about Jessie’s final years.

RR: She was very long lived and died in the 1950s. She was apparently charming and lovable. And so, when she became an elderly lady, there were people who wanted to take care of her. She had a kind of magnetism that was unusual. I thought it was very unusual that this nurse of hers – playing a variation on the Walt Whitman nursing theme – just took to this old lady.

When she and her family moved to New Mexico in their station wagon, they took the old lady with them. She was probably ninety years old at that point. So, there was something of Walt’s charm, or maybe Mrs. Whitman’s charm, or the family charm, in this daughter of Jeff’s.

In the 1940s, an independent researcher went to Long Island’s North Fork, to Greenport, looking for Whitman relatives. She found two daughters of his sister Mary Elizabeth, who had lived out there. They were really big, robust women with spookily clear blue-gray eyes that people said Walt and George both had. They were very handsome large women.

RC: So, it’s possible there are Whitman descendants walking among us.

RR: Yes. And that researcher wrote some wonderful stuff about Whitman haunts on Long Island: where he taught and so on. It was very like her to have stumbled on these Whitman women.

RC: On the subject of Walt’s mother helping to shape Leaves, I thought this was a very fitting psychological assessment. He said the “reality, the simplicity, the transparency” of his mother’s life were “responsible for the main things in the letters, as in Leaves of Grass itself.” Those three adjectives – reality, simplicity, transparency – describe something essential about the style and modernity of the first edition.

RR: Yeah, and the fact that he slowed down to say it so precisely, what he got from her. Right there, that’s a strong testimony to her importance to him. You know, all sons have a “nice mother,” a “good mother”; after the mother passes on, her memory is precious to them. But they don’t spell it out so carefully. As we were saying, she was a great mimic and a great storyteller, with a natural sense of drama. And he got that from her.

I found her character fascinating. Walt uses “mother” as a general term, but often he seems to be talking about his own mother as this calm benign good solid enduring presence in the home. But what I saw in the letters is that she was also a snake, and sharp. She got a case on her daughter-in-law. She had this adoring daughter-in-law who could never please her. And she said vile, vicious things about people. In her letters to Walt, she really expressed herself. She was nothing like that pious angel in the home.

I mean, if you and I were the guests, and Walt was bringing us home one day in 1853, we might have that impression of Mrs. Whitman. She’d be wearing a clean Quakerish outfit, and she’d be a lovely woman who’d serve us up a nice dinner, and she might say a couple of witty things. She was very kindly. But she had her moods. She definitely had a sharp side.

As far as making her an interesting person, that was significant to me. I read those letters of hers, and I had the impression of a complex, rich personality. A very interesting woman.

I really enjoyed this series. I’d picked up Roper’s book back in August at the bookstore in Harper’s Ferry and was delighted with the find. It was nice to get a behind-the-scenes look from the author’s perspective.

One of the wonderful things about this blog (and there are many) is that you see the Civil War in its context of 19th century America. What a change from a “Battles and Leaders” approach. As lovers of the past, we need both. I certainly hope the World Wars get the same elegant treatment somewhere on the Internet/in books/ in visual works. Heck–I hope we all learn from each other that history is just as complex as Walt Whitman’s mom!