Battlefield Art—with National Geographic Magazine and Author Harry Katz

Emerging Civil War is pleased to join with National Geographic magazine to share with you some of the work of author Harry Katz, whose article “A Sketch in Time” is featured as the cover story of the May 2012 issue.

In the coming weeks, we’ll bring you an interview with Katz, whose new book, The Civil War Sketch Book, was released on May 14. In the meantime, take a look at some of his great work from the May edition of National Geographic magazine:

At the time of the Civil War, camera shutters were too slow to record movement sharply. Celebrated photographers such as Mathew Brady and Timothy O’Sullivan, encumbered by large glass negatives and bulky horse-drawn processing wagons, could neither maneuver the rough terrain nor record images in the midst of battle. So newspaper publishers hired amateur and professional illustrators to sketch the action for readers at home and abroad. Embedded with troops on both sides of the conflict, these “special artists,” or “specials,” were America’s first pictorial war correspondents. They were young men (none were women) from diverse backgrounds—soldiers, engineers, lithographers and engravers, fine artists, and a few veteran illustrators—seeking income, experience, and adventure.

It was a cruel adventure. One special, James R. O’Neill, was killed while being held prisoner by Quantrill’s Raiders, a band of Rebel guerrillas. Two other specials, C. E. F. Hillen and Theodore Davis, were wounded. Frank Vizetelly was nearly killed at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862, when a “South Carolinian had a portion of his head carried away, within four yards of myself, by a shell.” Alfred Waud, while documenting the exploits of the Union Army in the summer of 1862, wrote to a friend: “No amount of money can pay a man for going through what we have had to suffer lately.”

The English-born Waud and Theodore Davis were the only specials who remained on assignment without respite, covering the war from the opening salvos in April 1861 through the fall of the Confederacy four years later. Davis later described what it took to be a war artist: “Total disregard for personal safety and comfort; an owl-like propensity to sit up all night and a hawky style of vigilance during the day; capacity for going on short food; willingness to ride any number of miles horseback for just one sketch, which might have to be finished at night by no better light than that of a fire.”

In spite of the remarkable courage these men displayed and the events they witnessed, their stories have gone unnoticed: Virginia native son and Union supporter D. H. Strother’s terrifying assignment sketching the Confederate Army encampments outside Washington, D.C., which got him arrested as a spy; Theodore Davis’s dangerously ill-conceived sojourn into Dixie in the summer of 1861 (he was detained and accused of spying); W. T. Crane’s heroic coverage of Charleston, South Carolina, from within the Rebel city; Alfred Waud’s detention by a company of Virginia cavalry (after he sketched a group portrait, they let him go); Frank Vizetelly’s eyewitness chronicle of Jefferson Davis’s final flight into exile.

Be sure to check out the May 2012 issue of National Geographic for the rest of Katz’s article. You’ll also find an excellent collection of battlefield sketches. Here’s a sneak-peak at a few of them:

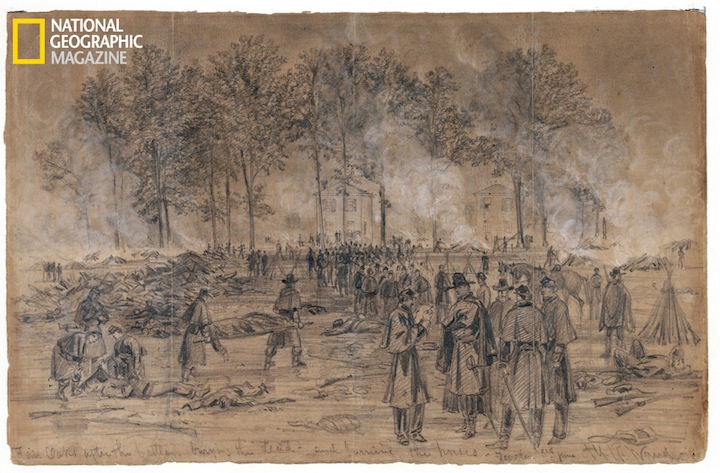

Union soldiers bury their comrades and burn their horses after the Battle of Fair Oaks. Alfred Waud, on assignment as a “special artist” for Harper’s Weekly, sketched the grim scene.

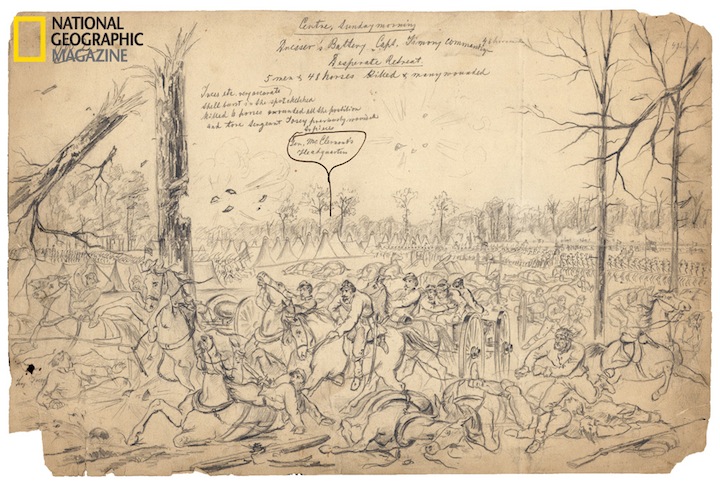

“Shell burst in the spot sketched [center left] killed 6 horses & wounded all the postition [sic] and tore Sergeant Tosey previously wounded in pieces,” wrote Henri Lovie. He called this scene the Union’s “Desperate Retreat.”

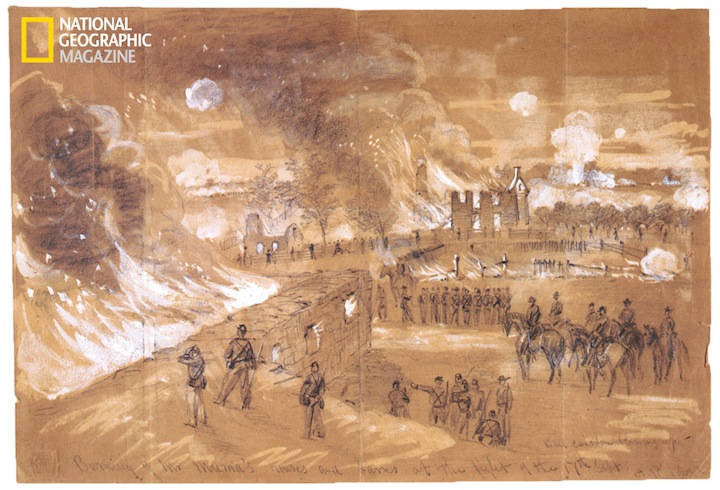

Confederates set Samuel Mumma’s farm ablaze to keep it from Union hands. By the time Alfred Waud made this sketch, using Chinese white pigment to depict flames, Union troops were in control of the area.

National Geographic‘s May 2012 issue also features the work of photographer Richard Barnes, who used Civil War-era photographic techniques to “create authentic-looking, intriguing images of Civil War reenactors alongside trappings of the modern world.”

(Our thanks again to National Geographic for sharing these excerpts!)