In Jumping Broke My Leg: Another Look at the Lincoln Assassination Legend

Today we welcome guest author Cal. J. Schoonover. Cal hail’s from Janesville, WI, where he lives with his son James. Cal is a graduate of The University of Wisconsin, Whitewater; and is currently attending American Military University, where he is pursuing his Masters in Military History, with a concentration in the American Civil War.

History says Presidential Assassin John Wilkes Booth broke his leg as he made the jump from the President’s Box to the stage, claiming Booth’s spur was caught on the red, white, and blue flag that draped the front of the area where the Lincoln party sat. In the 21st century however, historiography must go toe-to-toe with forensic history. Upon a closer examination of primary sources, including letters from both Booth and the doctor who treated him, there is now a greater possibility of creating doubt over when Booth actually broke his leg: was it as he landed on the stage at Ford’s Theatre, or later in the evening as he raced away from the scene of the crime?

President Lincoln, his wife Mary, and two guests, Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris, were late arriving at the theatre for the start of the play. The Lincoln party made its way to the Presidential Box, on the right-hand side of and elevated from the stage. Unbeknown to any of them, a man by the name of John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor was approaching the Presidential Box as well.

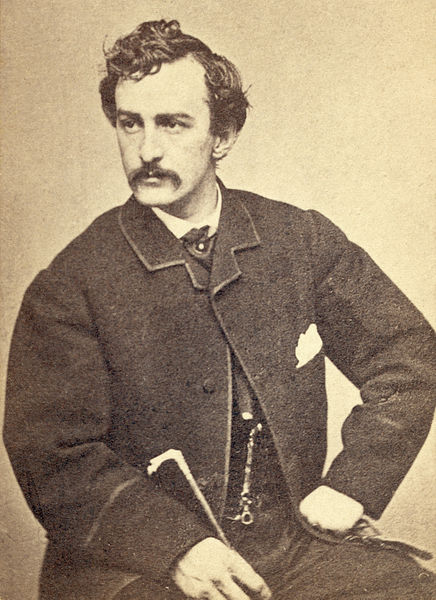

John Wilkes Booth was born on May 10, 1838 near Bel Air, Maryland. Booth was the second youngest of ten children. His father, Junius Brutus Booth, was a famous actor and was eccentric, with a reputation for heavy drinking. John and his siblings were raised on a farm, which was worked by the family’s slaves. As a child, Booth attended the Milton Boarding School for Boys and later St. Timothy’s Hall. To those who knew him, it seemed only natural that he would follow in his father’s footsteps by being on stage.

As Booth neared the Presidential Box, Charles Forbes, a personal assistant to the President, stopped him. Booth calmly showed Forbes something, but what exactly is unknown.

He was allowed to pass, whereupon he entered the Presidential Box as quietly as he could and wedged a piece of wood between the door and the wall. This would prevent anyone from entering.

Booth then crept up behind Abraham Lincoln and raised his .44 caliber pistol to the back of the President’s head. He shot at point blank range, and then sprang toward the front of the box. But before Booth could make good his escape, Major Rathbone sprang from his seat and was able to get a momentary grasp on Booth. Booth began slashing at Rathbone with a large knife he had also carried into the Presidential Box. Major Rathbone received a bone-deep wound to his left arm and fell to the floor, bleeding copiously. Booth was then able to break free. He jumped over the railing of the Presidential Box and landed on the main stage.

In his diary, Booth recorded his thoughts and descriptions of that night. To better illustrate some possible discrepancies among versions of events, these should be examined one claim at a time. Once in the Presidential Box–just before Booth pulled the trigger–he wrote, “I shouted Sic Semper before I fired.” There are several witnesses that claim not to have heard anything before the shot was fired, including those in the box with the President. One eyewitness, James P. Ferguson, was located in the Dress Circle of the theatre. Ferguson claimed that Booth yelled “Sic Semper Tyrannis” after firing the shot and jumping out of the box.

Therefore, according to Ferguson, it was while on stage that Booth yelled out and not while in the Presidential Box. Another eyewitness confirmed Ferguson’s account. Samuel Koontz also claims to have seen Booth as he was running across the stage, “exclaiming Sic Semper Tyrannis.”

Booth then made the claim, “in jumping broke my leg” when he leaped from the Presidential Box to the stage. But did he? This claim by Booth is also differed from what eyewitness’ saw. The first witness, A.M.S. Crawford, was also seated in the Dress Circle part of the theatre. Crawford stated that on the night of the assassination, “I saw him (Booth) as he ran across the stage.” Actor Harry Hawk, who was on the stage when Booth jumped, observed Booth, “rushing toward [him] with a dagger” in his hand. There were other people in the theatre that night who also claim to have seen Booth run, not limp, across the stage. These witnesses included William Withers, Sheldon P. McIntyre, John Downing Jr, Dr. Charles Sabin Taft, Major General B.F. Butler and Samuel Koontz, who was mentioned above. These people made statements that, after landing on the stage, John Wilkes Booth ran out of the theatre. None of them described Booth limping or seeming to be in the slightest bit of pain.

The account of the man who held Booth’s horse outside the back door to Ford’s Theatre should be examined as well. His name was Joseph “Peanuts” Burroughs, and he was a stagehand at Ford’s Theatre. Ned Spangler, another stagehand and one of the men involved in the plan to kill the President, gave him the job of holding Booth’s horse. Spangler was later arrested and charged with conspiracy. Initially, Spangler held Booth’s horse, but was called to do some work during the play. Spangler asked Burroughs to take over holding the horse. “Peanuts” Burroughs stated that, as Booth came racing out the back door of the theatre “he struck me with the butt of a knife, and knocked me down. He did this as he was mounting his horse, with one foot in the stirrup.”

While Burroughs did not mention which leg Booth placed in the stirrup, one has to assume he mounted his horse on the left side, which would require Booth to use his left leg. Had Booth actually broken his left leg in the theatre as he claimed, he would not have been able to use his left leg to hoist himself into the saddle. Nowhere in Burroughs’s statement is the claim made that Booth appeared to be in pain when mounting his horse. Mary Jane Anderson lived behind Ford’s and was looking out the window and had a clear view of the back alley of Ford’s Theatre, said in her statement on May 16 1865, “I saw Booth come out of the door with something in his hand, glittering. He came out of the theatre so quick that it seemed as if he but touched the horse and it was gone like a flash of lighting.” Both Burroughs and Anderson gave a description of someone who appeared to be in no sort of discomfort whatsoever, much less a person with a broken leg.

Author and historian Michael W. Kauffman noted in his book American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies that “almost all eyewitnesses at Ford’s reported seeing Booth crouch or stagger…but they noticed no sign of pain, in movement or expression.” Sergeant Silas Cobb, who was placed in charge of guarding the Navy Yard Bridge that led out of Washington toward Virginia, confirmed the previous eyewitness accounts when he said that he did not notice Booth to be in any type of discomfort when he crossed the bridge. So if Booth did not break his leg at the theatre, when exactly did he?

As Booth made his way across the Navy Yard Bridge, his fellow co-conspirator, David Herold, crossed shortly after Booth without any trouble from Sergeant Cobb. The plan Booth made was to meet up with his fellow conspirators just outside Washington and ride south into Virginia, where he thought he would be safe. However, due to unforeseen problems, Booth would not be able to make the distances he so badly wanted.

Once David Herold was over the Navy Yard Bridge he continued to riding south into Maryland, where he met up with John Wilkes Booth. At this time, according to Herold, Booth said “that his horse had fallen or he was thrown off, and his ankle sprained.” To back up what Booth told Herold, when the two men arrived at John M. Lloyd’s house at Surrattsville in Prince George County MD, where they were supposed to pick up supplies that were left for them, Booth told Lloyd that he broke his leg when his horse fell. Lloyd stated he “seemed to be in great pain.” Lloyd also mentioned that Booth did not dismount, unlike Herold, who was the one that knocked on his door to wake him. Just before Booth and Herold rode off, Booth said to Lloyd “we have killed President Lincoln and Secretary Seward.”

Booth and Herold then went looking for a doctor to tend to Booth’s injured leg. Booth wrote in his diary that he “rode sixty miles that night, with the bones of my leg tearing the flesh at every jump.” The doctor the two men were looking for was Dr. Samuel Mudd, who was about thirty miles away, not sixty as Booth claimed. When the two men arrived at the Mudd farm in Charles County, Maryland, it was around four in the morning. Herold dismounted and knocked loudly on the doctor’s front door. When Dr. Mudd answered, he observed the two men, who he claimed appeared to be in distress and in need of assistance.

Mudd then invited the men in and had the injured one lie on the sofa in the parlor; when Dr. Mudd later retold this story, he claimed not to have known either man. Dr. Mudd, in his statement of May 16th 1865, described Booth’s leg “as slight a breaking as it could possibly be.” The doctor continued on and said “the patient complained also of a pain in his back.” Although Mudd examined Booth, he could see no reason for his back pain “unless it might have been in consequence of his falling from, his horse, as he said he had done.” This was one of the few times Booth told the truth and if Booth did in fact have a slight back injury, it backs up the claim he did, in fact, fall from his horse.

When Dr. Mudd finished setting Booth’s broken leg, he allowed him to rest in an upstairs bedroom where Booth would have some privacy. Dr. Mudd then gave instructions to his hired help to care for the two horses. It was the statement of one of the farm hands, Thomas Davis, which helps back up the claim of an accident with the horse. Thomas Davis noticed that one horse “had been hurt; his shoulder was swelled right smart.”

Davis also said the small bay had a “piece of skin off on the inside of the left foreleg about as big as a silver dollar.” Another comment Davis made was that Mrs. Mudd told him the injured man had fallen from his horse in Beantown and would be on their way now that Dr. Mudd fixed him up.

It seems very possible from what has been presented above that what we all assumed to know about the events following Booth’s shooting of President Lincoln could be, in fact, wrong. From middle school onward, we have read about John Wilkes Booth jumping from the President’s Box at Ford’s Theatre and allegedly breaking his leg. Could it be that history has been presented to us incorrectly? As time passes, more information and theories continue to be brought forward. To the best of my ability, I have tried to avoid giving wild speculation about Booth. I have simply examined what people of the time said, including Booth. However, what would be the point of Booth claiming he broke his leg in the Theater if in-fact he broke it when he fell from his horse? One reason would be because of the embarrassment Booth felt from falling. Can one imagine the humiliation Booth would have felt if people would have known the famous assassin of the “tyrant” Lincoln had fallen off his horse? I think Booth felt it sounded a lot more heroic when he made the claim “in jumping, broke my leg” after shooting Lincoln.

I end here with what I consider to be solid evidence of a real possibility that Booth did not break his leg at Ford’s Theatre, but while he was riding to meet up with his fellow conspirator, David Herold, when his horse fell. Also, Booth did have a small broken bone in his left leg, and complained to Dr. Mudd that not only was his leg injured, but so was his back.

This is consistent with a riding accident. Additionally, the story of the fall from the horse was told to more than one person, including Herold. There is also a confirmed report of an injured horse. Booth would have no reason to lie at this point, and with the statements above, it seems we now have the true way John Wilkes Booth broke his leg.

Fascinating. Thank you. Once again we discover that sometimes an examination of the primary accounts, combined with a little common sense, offers up a very perspective of a particular event or events. I have seen it in my own research time and again, and with some of the books we publish.

Fortunately for you, there are not too many folks emotionally invested in Booth’s inherent goodness–or you would be attacked, slandered, and otherwise pilloried before the Bar of Blogs (mostly by folks who would not have bothered to read what you wrote), forced to repent, and then burned at the stake to cleanse your soul.

Keep up the good work.

tps

Ted, thank you for your words. I’m happy you enjoyed what you read.

Cal

Well, look who I found here! Congrats, Cal. Excellent, hard work. Nice comments as well. Can you tell I am totally smiling?

Thanks Meg for your help with the editing. You were a big help 🙂

Interesting and well constructed article, but not completely objective. The bone Booth fractured was the left fibula, which is the small bone which reinforces the tibia, or shin bone. It’s most commonly fractured when landing off-balance from a high jump. Since it’s a non-weight-bearing bone, walking or even running is quite possible, although painful. Several eye-witnesses in the theater audience did report seeing Booth favoring one leg as he ran across the stage. During his flight, Booth told strangers his leg was broken when his horse fell to avoid suspicion. He had no reason to lie about it when writing in his diary.

Which eye witnesses report seeing Booth favor his leg while in the theater? Name them. David Herold and Dr. Mudd weren’t “strangers”. Who are these strangers you are referring to?

i feel that it would be much better to state that no one will fully know the truth than to put out dis-information or false information. I feel more inclined to believe that he broke his leg jumping from the stage than this new story which has seemingly emerged from nowhere. Listen, if you were fleeing for your life and speed was of the essence, youd’ move pretty darn quick yourself. Same with mounting the horse. I have read that the mounting of the horse was NOT that quick or easy, that the horse was jumpy and difficult….. so, the people that say that the injured horse is proof, don’t have much of a “leg” to stand on either since that horse could easily have banged itself up while colliding with the bench or whatever else was in that alley. Anyway, the fibula is NOT a weight bearing bone…. you CAN get around with a broken fibula if you have to. Had he broken the tibia or main leg bone, there would have been no escape. And never forget that Booth’s terror of being caught and the massive adrenaline rush from what he’d just done truly propelled him out of there like a rocket….. i’m pretty sure he didn’t even feel leg pain till later. In the final analysis, Booth spells it out pretty clearly in his diary…. he explains in a sequential way “went into the box, shot him, jumped to stage, road 60 miles, etc ” The way HE put it, the fact of his jumping to the stage is placed right after the fact of him being in the box, there is a clear order. Michael kauffman has gone so far as to say that Booth landed on his right foor !!! If we were not there, we canNOT say. I feel that it makes far more sense to believe the original story and the idea that some people want attention and will go so far as to create this new version is annoying.

The statement, “I broke my leg when my horse fell with me,” first appeared when Doctor Samuel Mudd was questioned about “the two men who stopped at his house after the Assassination.” Supposedly, this is what Booth told Mudd; and was used by Mudd to explain why John Wilkes Booth sought him out.

The problem: Booth made his living as a liar — also known as ACTOR — and could adopt personas at will; and concoct fabulous, believable stories on demand. Also, Dr. Mudd was an early participant in the kidnap conspiracy; and he may have deliberately spread false information to divert attention from himself.

More information about John Wilkes Booth and his visits to Canada, New Orleans, the Surratt family… becoming more accessible all the time. (Boothie Barn has an excellent collection of the latest information.)

“Seemingly emerged from nowhere”. He wrote an excellent article and quoted actual sources. What’s annoying about that? You’re response has much more speculation. “The horse could have hit a bench”. Come on.

Possibilities:

1. Booth broke his leg when his horse fell (and there’s evidence of a horse fall), but Booth lied in his diary. Maybe. This assumes a lying Booth. Claims that Booth as actor was a professional liar ring false without more evidence of habitual lying: Actors are not professional liars, and most can tell the basic difference between lying and telling the truth in their lives off the stage, although we all bend the truth and have our own subjective memory and way of perceiving.

2. Booth broke his leg when he jumped from the stage, and the reports about a leg injury in a horse fall were lies to cover the fact that he was the assassin. Maybe. But why would so many lie about the horse accident and horse injury?

3. The leg was injured twice: first in the jump from box to stage, and then again, in a horse fall (so in this case, Booth’s claims in his diary were truthful about the effect of the jump on his leg, AND the claims of evidence from the farm hand who tended the horse are also true as are Booth’s statements of leg injury from a horse fall.

We may likely never know for certain, but I tend to think it’s #3, both.