Grant Takes Command

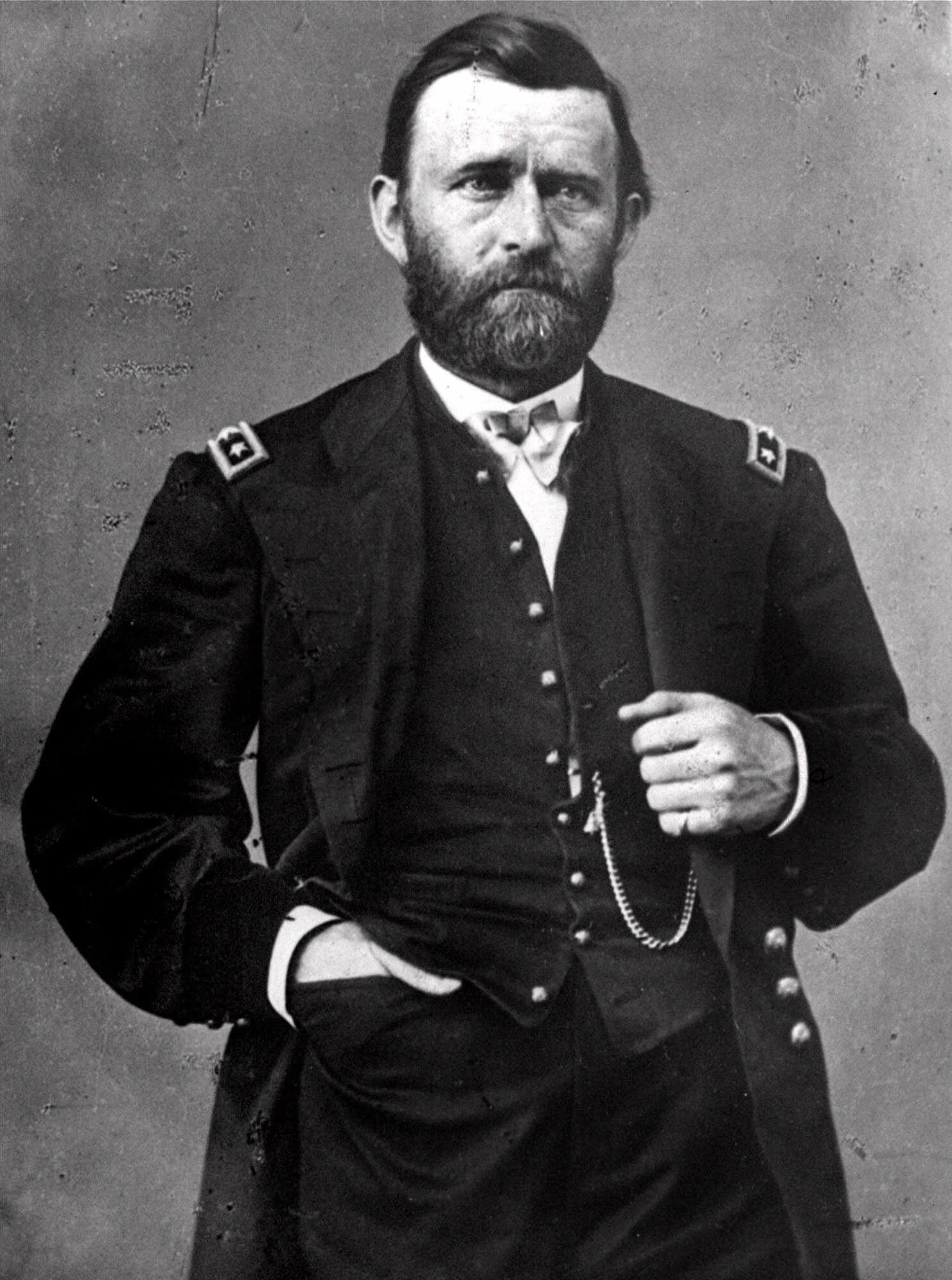

This weekend marks the 150th Anniversary of Ulysses S. Grant’s promotion to Lieutenant General and designation as Commanding General of the U.S. Army. Often discussed in passing as regards the 1864 campaigns, to contemporary eyes this was a major event in the war. Grant’s promotion reveals much about the political and military undercurrents in March 1864.

Recreation of the rank of Lieutenant General was no small thing. Only the two most prominent soldiers in American history up to that time (George Washington by substance and Winfield Scott by brevet) had held this rank before, and in the 1864 mind whoever next got this rank would be placed into their pantheon. By making Grant a Lieutenant General, Lincoln doubled down on the idea that Grant was the man to win the war. (To put this in modern terms, it would be like recreating the General of the Army rank and giving a current General a fifth star – something that was proposed for David Petraeus about five years ago.) The prestige was immense but so was the pressure to live up to the rank; this is what Lincoln meant when he told Grant, “With this high honor, devolves upon you, also, a corresponding responsibility.”

Grant’s third star was required to give him sufficient rank and stature to command more senior officers still in the field, of which there were several. It also neatly sidestepped a potential political issue, because Grant was junior to the shelved (but still on the active rolls as seniormost Major General) George B. McClellan.

Grant’s role was only 43 years old in 1864 – scarcely older than its occupant. Before formal creation of the job of Commanding General in 1821, whoever happened to be the Army’s senior officer on active duty was the overall commander. From 1821 to 1861, there had been three Commanding Generals (Jacob Brown, Alexander Macomb, and Winfield Scott). Grant was the third Commanding General since the war began, succeeding Henry W. Halleck and McClellan before him.

Grant embraced his new role, and titled his headquarters “Headquarters Armies of the United States.” This impressive title also conveyed a message – all field armies were part of one coordinated team, and he would move them as such. It was the first signal that a new leader with a different outlook was in place. The next thirteen months proved the wisdom of Lincoln’s choice.

Reblogged this on Practically Historical.