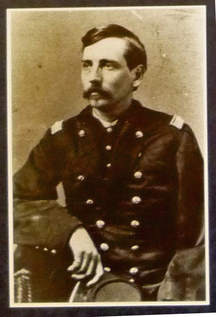

The Kennesaw Line: In Memory of Frederick Bartleson

We all have our stories—some of them are long, some are short—and we all have our graves. Thus 150 years ago today, one of my favorite stories from the Civil War ended on the Kennesaw Line, that being the life of Col. Frederick Bartleson of the 100th Illinois Infantry.

I came to know Fred many years ago through a friend who was one of his descendents, Mike Bubb. Bartleson’s story caught my attention due to his hopeless one-regiment charge against Longstreet’s juggernaut at Chickamauga. However, there was more to him than that one chapter.

Frederick Bartleson was born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1833, but grew up in Brooklyn, NY, and Freehold, NJ, where his father edited the Monmouth Enquirer. Fred had a good education and graduated from Alleghany College of Meadville, PA, with a degree in law and passing the bar at the age of 22. He traveled west to Joliet, Illinois to practice. In Joliet he quickly became a popular citizen, known for “his sterling qualities of mind and heart.” Fred was elected district attorney and married Kate Murray.

When the war clouds gathered after the firing on Fort Sumter, all eyes came to lay on Frederick Bartleson because he became the first volunteer for service in Will County, “an act more eloquent than words, and the example more effective than eloquence.”

Bartleson helped with the organization of the local men into what became a company in the 20th Illinois Infantry, and he was in turn elected captain. He led them through the fighting at Fort Donelson and then again at Shiloh, as major of the unit. At Shiloh, he was severely wounded in the left arm while conducting a reconnaissance; the arm had to be amputated. Coming home to recover from his wound, he was urged by some to retire, but he stated “No! I have still an arm left for my country, and she shall have that too if need be.”

While he was in Joliet recovering, another unit was being formed in the county, the 100th Illinois. Bartleston was given command of the regiment, and when they departed for the front, their one-armed colonel led the way.

The 100th first saw service in Kentucky, but missed the fighting at Perryville, instead having their baptism of fire at the battle of Stones River as part of the Union defense of the Round Forest. After the fight, Bartleson and his men were noted for their good conduct in the severe fight.

The battle of Chickamauga would see hard fighting for the 100th. Then, in a desperate moment, Bartleson ordered his regiment to charge a force of unknown size in the woods just east of the Brotherton Farm. The force proved to be the entire Confederate left wing—more than 30,000 men who had just began a juggernaut assault into a gap in the Union line. The following fight was quick, brutal, and ended with expected results. Many men of the 100th, Bartleson included, were sent off to Confederate POW camps. Bartleson was held for six months at Libby Prision in Richmond, before being exchanged and given leave to return once more to Joliet in the spring of 1864.

While home once more, he was again urged to resign and enter politics. “I want no nomination, and no office but the one I know hold,” he replied, “and I shall return to my post and give my life if need be, to secure to us a free government.” Bartleson then returned to his regiment jus in time to enter the field with it for the Atlanta Campaign.

During the days of May, as the Campaign took on its grueling nature, the soldiers could be sure that their one-armed Colonel was always with them, leading them from the front through many of the engagements. On June 23, though, he was not with the 100th; that day, Bartleson was the division officer of the day and was working with the skirmishers of his brigade. According to the history of the 100th Illinois, “The forenoon was very quiet, and he came into regimental headquarters about one o’clock to dinner, and then returned to the line, and soon after the artillery opened for a few minutes, then the skirmish line was ordered to advance, one brigade going to its support. While directing his line, the Colonel was obliged to pass a point which was exposed to the enemy’s sharpshooters, and he was hit and killed instantaneously. The stretcher bearers of the 57th Ind., (the regiment on the skirmish) seeing him fall went to him at once, and finding him dead, carried the body back of a barn near by, and sent us word. Our own bearers were immediately sent out after the body and brought it in, and the regiment then passed in review by the body to take their last hasty look at one they had so loved and honored. The body was then carried back to the rear, to a spot which had been appropriate as a division cemetery. Generals Harker, Newton, and Wagner, came up and exhibited much feeling at the sight. The body was then sent home with an escort from the regiment.”

Thus ended the story of Col. Frederick Bartleson, joining the ever-growing list of talent on both sides that were falling in the constant war of sharpshooting and long-range artillery fire.

So interesting thanks so much! What a great man!

The question as to why Bartleson charged at Chickamauga on the 20th has arisen on several occasions. In minutes of an annual report of a reunion of the 100th several of the former officers are referenced as stating that they distinctly remember an officer from General Wood’s staff riding into the regiment an ordering Bartleson to investigate a masked battery observed on the edge of the woods to his front. Needless to say, the controversy that was to follow over the “Fatal Order” between Woods and Rosecrans overshadowed any such details that may have involved a regiment. For more interesting details on Bartleson’s leadership is a study of the Battle of Latimer Farm. Just after his return from Libby he led the brigade through a blinding thunderstorm driving the Confederate forces out of the Mud Line and back to positions on Kennesaw.

I think it is a little ironic that while most of the battles in which the 100th fought are usually covered in detail the one where they played the most seminal role is largely overlooked. Helping turn Cheathem’s cavalry at Spring Hill.

Great article Thanks fir remembering Uncle Fred. Huzzah for the Bully Colonel.of the Brigade!!!

My Great great grandfather; Levi Claire Rice was apart of the 100th Illinois at Chickamauga during that attack. He was wounded, captured, later exchanged, and past away in Nashville Tenn. He is buried at the National Cemetery in Nashville Tenn. Has I write this, it is after I walked the field where he was wounded at Chickamauga. Bless all who parishes there.

My great 3x grandfather also served in the 100th Il , His first battle was at Stones River after the battle he became sergeant. My grandfather died in that charge, some family say it was from artillery fire yet I have never found any evidence to prove that. I have visited the Chickamauga cemetery four times and have also stood in the feild where these brave men fought and died. I still have his enlistment papers including a period photograph of him in his fresh Union Uniform. I have searched high and low for any additional information of the 100th and my grandfather. there was a book written about the 100th, long out of print but can be found to read on the internet. I am always looking for additional information on the 100th, thank you for sharing your grandfathers experiences. there is a Joliet History Museum with the 100th Battle flag and other period artifacts if you are interested.