Shaping Chancellorsville: The New “Heart of the Battlefield”

Part seven of a series

Throughout the seventies, Fredericksburg and Spostylvania National Military Park (FSNMP) continued to fill interior gaps in its land holdings. A pair of major acquisitions came in 1973 and 1975 that opened new ground and, ironically, redefined “the heart of the battlefield.”

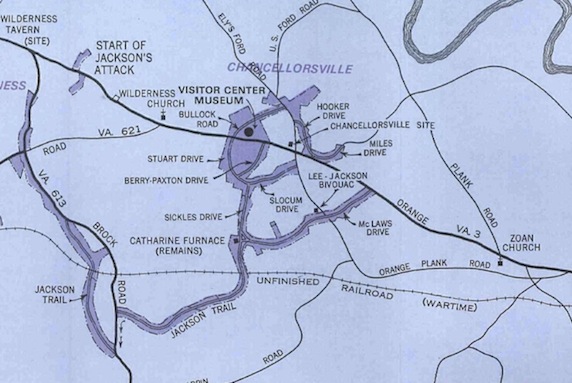

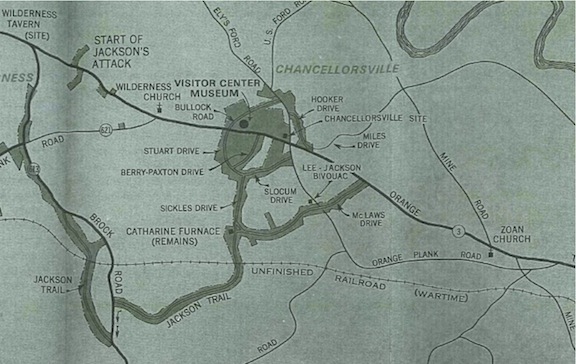

“Of the many historic sites on the four battlefields that are within the Park’s proposed boundaries, none is more important than the one on which is located the foundation ruins of the Chancellor House…” wrote park historian Thomas Harrison.[1] The property was situated at the Chancellorsville intersection itself, at the junction of Route 3, Ely’s Ford Road to the north and the Orange Plank Road to the south.

As early as 1964, the chief historian had advocated for the purchase of two acres of property at the Chancellorsville intersection, including 200 feet of frontage along Route 3, at a price of $4,000.[2] “This is a minimum recommendation for site acquisition in an area in which we should have maximum efforts to preserve battlefield integrity,” he wrote.[3]

It would be nine and a half years before the park could acquire the intersection, however, at a price tag far higher than Harrison suggested and as part of a deal far more complicated than he would have imagined.

On Friday, July 20, 1973, after four years of negotiations, FSNMP announced the acquisition of the intersection—“which park officials described as the most critical area needed to tell the story of that Civil War battle,” The Free Lance-Star reported.[4] As part of the deal, the park received a total of 99 acres; in exchange, it paid $125,326 and exchanged 327.35 acres of “less historic and underutilized pieces of park-owned property.” Included in the swap were 233.48 acres of property at Shenandoah National Park at Luray and 94.37 acres of FSNMP property, including Miles Drive at Chancellorsville.

In its press release about the property, FSNMP described it as “the site of the famous house which gave its name to the battle” and said the tract “includes vital territory which is literally the heart of the battlefield.”[5] The release went on to offer a one-sentence history of the building before mentioning that it was used by Hooker during the battle. “The final Confederate victory came when the house and its surroundings were captured,” it said. “Jubilant Confederates celebrated the triumph in a roaring tribute to R. E. Lee when he rode into the area.”[6] This is, of course, the central image of the “greatest victory” story.

In reporting the acquisition, the newspaper picked up a theme offered by the press release, saying, “The tract…is significant because it is the site of the Chancellor house that gave its name to the battle of Chancellorsville.”[7]

The change was noted immediately on the park’s driving tour map, updated for 1974, although no specific mention of the intersection appears in the brochure’s updated text.

“The acquisition of the house site itself is only the first of several purchases we hope to make in the great open clearing at the Chancellorsville crossroads,” Freeland wrote in a letter the following January to a descendant of the Chancellor family. “The next most critical spot is the tract of some 28 acres which includes the Chancellor cemetery.”[8]

Within months, as it turned out, Freeland’s attention would be keenly focused on that tract.

————

[1] Harrison, Thomas. Memo to FSNMP superintendent. 1 February 1964.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Patterson, Helaine. “Park addition is key.” Free Lance-Star. 21 July 1973.

[5] FSNMP. “Key Chancellorsville Site Added to National Park.” Press release. The release is undated, but a 24 July 1973 memo from FSNMP superintendent Dixon Freeland to the director of the NPS’s Virginia state office mentions the release as part of an “action plan,” both drafted on 20 July 1973. The action plan also mentions that “Bob [presumably Krick] will write this today, to be released in Saturday’s paper.”

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Freeland, Dixon. Letter to Mr. Philip Mattiessen Chancellor. 21 January 1974.

I’m not following how the park “traded” land. Was the land at FSNP and Shenadoah go to a developer? Odd to hear land being “traded” when we are in a time of property being saved by organizations like the Civil War Trust and others.