Coffee in the Civil War

Today, we are pleased to welcome guest author Ashley Webb.

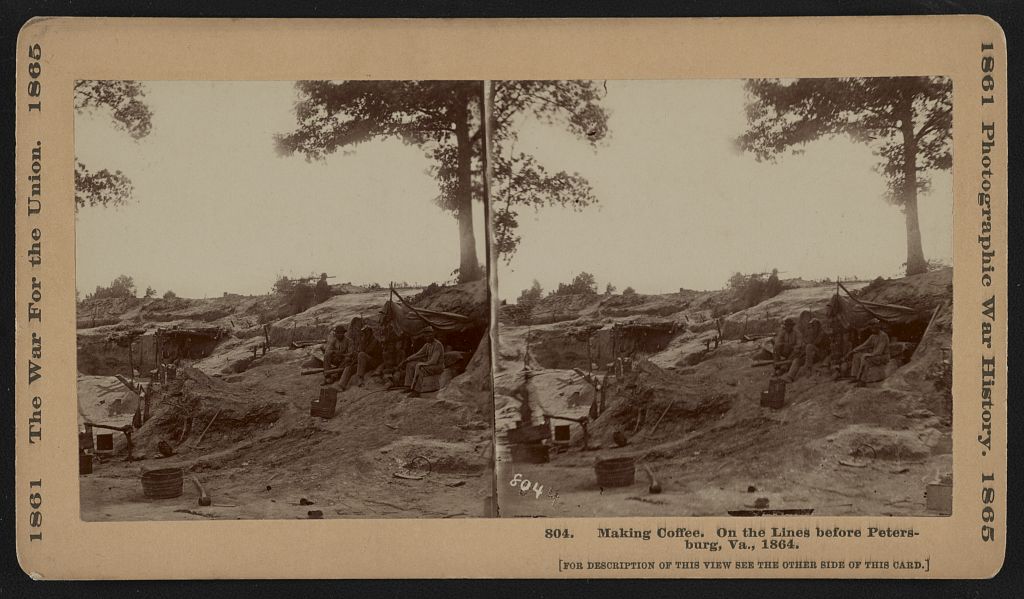

If you’re like me, every morning, I wake up and have a cup of coffee (or two or three). Coffee was also an essential part of a Civil War soldier’s routine. They drank their coffee whenever they could, refueling themselves for the long days and nights ahead.[i] And through the hardships of war, soldiers shared campfires, rations, and friendships. Coffee wasn’t always part of a soldier’s ration, though. It became a wartime staple thanks to President Andrew Jackson’s Army General Order No. 100 substituting coffee and sugar rations for alcohol in 1832.[ii] At the outbreak of the Civil War, and with the Union Blockade of Confederate ports in April of 1861, the availability of coffee to Confederate soldiers and families across the country dwindled. As a result, Confederate soldiers and families on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line devised unique ways of obtaining their coffee.

Shortly after the start of the war, the Union blockade halted the import of goods through Southern ports. This not only affected the influx of Confederate uniforms, weapons, and medicines, but also rations. In a rare case, Confederate officers reverted to pre-1832 rations, substituting whiskey for coffee. John Breckinridge, a soldier in the 28th Virginia Infantry, discussed this event in a letter to his sister, Eliza, while in camp near Fairfax Courthouse on October 13, 1861: “There is a good deal of drunkenness in camp now, they give the soldiers whiskey instead of coffee. They give them four days rations at once, and some of them drink all of theirs in a day.”[iii] This instance, however, seems to be a one-off occurrence even more so as the war continued, as whiskey was needed more as an antiseptic for wounded soldiers.

The lack of coffee didn’t stop some Confederate soldiers. Informal truces arose, and trades between the picket lines flourished. Because of the blockade, Union troops were unable to buy Southern tobacco, creating a common ground and an array of innovative ways for soldiers to acquire the unavailable. While in Fredericksburg, Virginia, one Confederate soldier slipped a note across picket lines that said “I send you some tobacco and expect some coffee in return. Send me some postage stamps and you will oblige yours Rebel.”[iv] Along the banks of the Rappahannock River, also in Fredericksburg, local folklore suggests that Confederate soldiers constructed small sailboats to send tobacco to Union forces on the other side of the river, requesting coffee to be sailed back when the wind changed. In another instance, James E. Hall, a soldier in the 31st Virginia Infantry, took part in a truce with Union soldiers on March 23, 1865, in which he exchanged newspapers with a Union soldier, and others in his company received coffee. Soon after, “the truce ended and both parties resumed the firing.”[v]

One of the more interesting aspects of the coffee shortages was the creative ways families and Confederate soldiers came up with alternatives. Roots and vegetables were ground up and sometimes blended together in the attempt to create a drink with the most coffee-like taste. Lt. Col Freemantle, a British officer visiting the Southern states in 1863 declared, “The loss of coffee afflicts the Confederates even more than the loss of spirits; and they exercise their ingenuity in devising substitutes, which are not generally very successful.”[vi] The possibilities were endless. Newspapers printed recipes for coffee substitutes as early as August of 1861. The North Branch Democrat, a Pennsylvania newspaper, in its October 22, 1862, issue provided several different blends of coffee substitutes, to include wheat, chestnut, sweet potato, carrot, barley, pea, and chicory root.[vii] Others popular substitutes included beets, acorns, cotton seeds, persimmon seeds, and asparagus seeds.

Sometimes families got extremely creative. One Arkansas True Democrat reader wrote the editor on October 17, 1861, describing his or her favorite coffee recipe using tan bark, old cigar stumps, and water, all boiled in a dirty coffee pot.[viii] In a tamer recipe, Julia Breckinridge, of Botetourt County, Virginia, wrote her mother-in-law on October 26, 1861, stating, “I tried the dandelion coffee the other night-and it is quite as good as any rio [coffee] I ever tasted. Jenny said she never would have known that it was not coffee if she had not been told so.”[ix] In a letter a few weeks later, Julia Breckinridge tells her husband, Gilmer, “We have taken to drinking rye coffee and I…never care to drink any other kind.”[x] A reader from Gwinnett County, Georgia agreed with Julia in the Savannah Republican on September 9, 1861:

“Sugar and coffee are getting scarce and high. The sugar we are learning to dispense with, and we have an excellent substitute for coffee, very cheap and abundant. It is rye—we have been using it in our family for six weeks, and I think it equally as healthy, and as palatable as the Rio….So you see as far as coffee is concerned, we don’t care a straw about Lincoln’s blockade.”[xi]

Out of all the substitutes, rye seemed to be the most popular for soldiers and families alike, but it had disastrous affects if not carefully cultivated and prepared. The Daily Dispatch, a Richmond, Virginia paper, reported a story on February 14, 1863, concerning the dangers of substituting rye in coffee. A German family of eight in Brooklyn, New York, was poisoned after drinking rye coffee purchased from a local shopkeeper. The newspaper included the letter from the Health Officer, who stated: “The case of Mr. Croft’s family is not a solitary one. I had become cognizant of numerous instances in which the rye coffee had the same or similar effects…. Nobody should be surprised at the obnoxious effects of rye coffee, for with the rye itself grow ergot and other poisonous plants, and unless their seed be carefully separated from rye, poisoning is inevitable.”[xii]

Coffee, a commonality in the Union and a luxury in the Confederate States, not only fueled the soldiers low on energy, but it brought unity between soldiers, comradery between lines, and an inexhaustible source of creativity among families. It has continued to be an essential part of everyday life, but today it is certainly easier to obtain!

[i] Billings, John, Hardtack and Coffee (Boston: George M. Smith & Co, 1887). https://archive.org/details/hardtackcoffee00bill

[ii] Davis, Brig. Gen. George B. The Military Laws of the United States, 4th ed, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908), 308. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=k6yLBuFN-JQC&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&authuser=0&hl=en

[iii] John Breckinridge to Eliza Breckinridge, 13 October 1861, Breckinridge Collection, History Museum of Western Virginia, 1969.51.627.

[iv] Confederate soldier to Union soldiers, 6 March, Missing Documents, National Archives and Records Administration, http://www.archives.gov/research/recover/missing-documents-images.html

[v] Hall, James Edmond and Ruth Woods Dayton, The Diary of a Confederate Soldier, (Lewisburg: University of Michigan Libraries, 1961), 128. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008191622;view=1up;seq=132

[vi] Sir Arthur James Lyon Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States: April, June 1863, (Mobile: S.H. Goetzel, 1864), 41. http://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/fremantle/fremantle.html

[vii] “Coffee Substitutes,” North Branch Democrat. 22 Oct. 1862, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86081912/1862-10-22/ed-1/seq-4/

[viii] “Recipe for the Times-To Make Coffee,” Arkansas True Democrat, 17 October 1861. Confederate Coffee Substitutes: Articles from Civil War Newspapers. http://www.uttyler.edu/vbetts/coffee.htm

[ix] Julia Breckinridge to Emma Breckinridge, 26 October 1861, Breckinridge Collection, History Museum of Western Virginia, 1969.51.630.

[x] Julia Breckinridge to Gilmer Breckinridge, 15 November 1861, Breckinridge Collection, History Museum of Western Virginia, 1969.51.636.

[xi] “Affairs in Gwinnett,” Savannah Republican, 9 September 1861, Confederate Coffee Substitutes: Articles from Civil War Newspapers. http://www.uttyler.edu/vbetts/coffee.htm

[xii] “Rye Coffee-Its Dangers,’ The Daily Dispatch, 14 February 1863, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1863-02-14/ed-1/seq-1/

Thanks Ashley for a great story on coffee during the Civil War. In a later Breckinridge letter, Gilmer Breckinridge tells of some side effects being mentioned from drinking rye coffee.

I’ll certainly have to check that out, Stan! I have yet to read about the side effects, so that would be a very interesting read!

Reblogged this on DailyHistory.org and commented:

The Emerging Civil War has blog post from Ashley Webb about coffee and the Civil War. During the war, coffee for Northern troops was an incredibly important staple and part of their rations, but for Southerners it was a rare luxury. Webb’s describes ad hoc armistices that allowed troops to trade coffee for tobacco across “the picket lines.” Confederate soldiers even attempted to devise coffee substitutes. Check out Webb’s post at Emerging Civil War.

Hello Ashley, It’s so nice to read something from my long lost cousin! Very nice article. You may remember your old cousin when about 20 years ago, (while in Garland for Aunt Doris’ funeral) you and your sister both “wore” me down into playing with all your girly possessions…dolls, etc. Your mother and grandmother chuckled at me for giving in.

It paid off, I now have 2 young daughters and one is riding English style.

Cousin Russell in Tampa