“Harvest of Death”: The Battle of Griswoldville

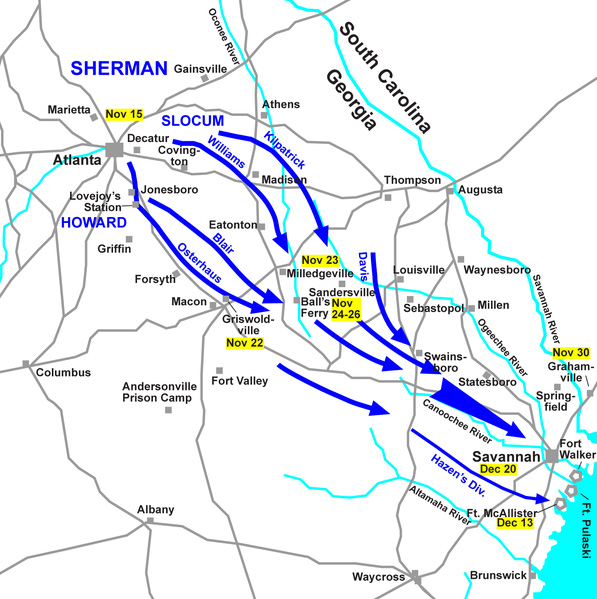

On November 15, 1864, the vanguard of William T. Sherman’s forces left the city of Atlanta, Georgia on what would become the March to the Sea. Their ultimate objective was the city of Savannah, about 250 miles away.

Over the course of about the next month, Sherman’s men moved across the Georgian countryside in a relatively unopposed march, besides for the occasional cavalry skirmish and run-in with home guard pickets. During the entire march, there were only two set battles: the Battle of Griswoldville, and, at the end of the march, the capture of Ft. McAllister. The first of those battles, Griswoldville, occurred 150 years ago, Nov. 22, about ten miles away from Macon, Georgia.

Hal Jesperson

cwmaps.com

The town of Griswoldville was named for Samuel Griswold, a Connecticut native, who had moved to Georgia before the war. Besides “a soap and candle factory, a pistol and saber factory… and several houses,” Griswoldville was also a station stop on the Central of Georgia Railroad. With its railroad link as well as valuable factories, the small town was a prime target for Federal cavalry under Judson Kilpatrick. Kilpatrick’s men galloped into the town on Nov. 20, quickly dispatched the Confederate guards, and set fire to the railroad depot as well as the weapons factory.[1]

November 21 saw Confederate cavalry under the command of Joseph Wheeler spend most of the day skirmishing with Kilpatrick’s men, until, by nightfall, the rebels’ numerical advantage pushed Kilpatrick about two miles away from the now burned-out depot of Griswoldville. Moved up to support Kilpatrick’s men and also protect a convoy of wagons was the 1st Division of the Fifteenth Corps, Army of the Tennessee, under the command of Brig. Gen. Charles Woods.[2]

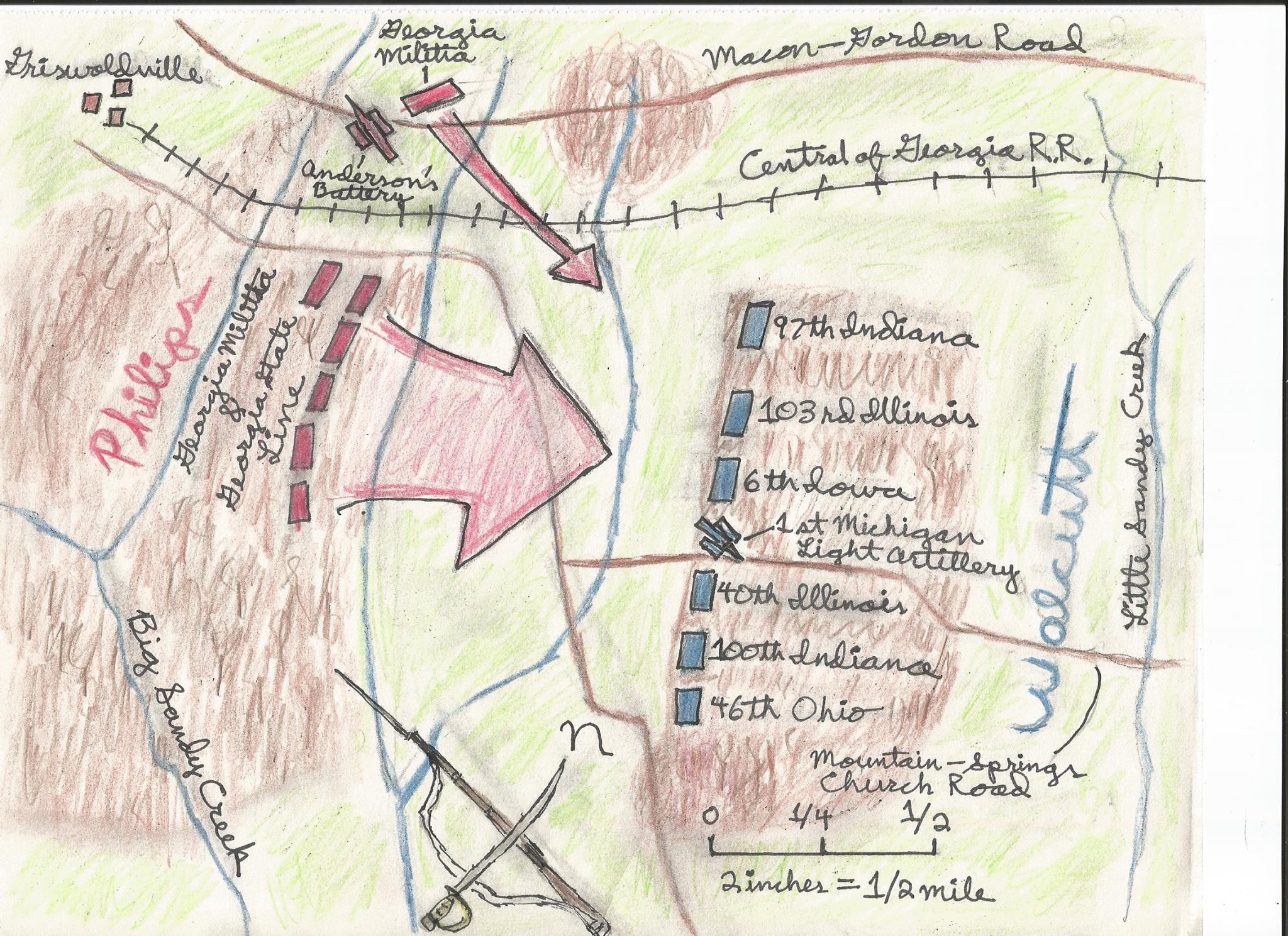

Tuesday, Nov. 22, came with a spattering of carbine fire as Kilpatrick and Wheeler continued to skirmish. In support of their mounted comrades, the Federal infantry also turned out. With the infantry was Maj. Gen. Peter Osterhaus, a Prussian-born officer who commanded the entire Fifteenth Corps. To support Kilpatrick, Osterhaus later wrote, “I consequently ordered one brigade…to move early on the south side of the railroad in the direction of Griswoldville.” The force Osterhaus picked from Woods’ division was the 2nd Brigade, under the command of Brig. Gen. Charles C. Walcutt.[3]

Born in 1838, Walcutt had been educated in the Kentucky Military Institute, and was a veteran of many of the Civil War’s western theatre battles.[4] On Nov. 22, 1864, he had seven regiments under his command totaling approximately 1,500; the regimental average was about 215 men and officers. They were also joined by a two-gun section of Battery B, First Michigan Light Artillery, under the command of Captain Albert Arndt.[5]

Walcutt’s men spent the morning hours of Nov. 22 marching down the road to Griswoldville and sporadically skirmishing with Wheeler’s cavalry. The rebel horsemen, not wanting to get involved with the Federal infantry, peeled off in the direction of “different roads,” according to Osterhaus’ report.[6]

With the gray-clad cavalry dispersed and the Union wagons largely out of danger, Walcutt’s brigade was recalled from its skirmishing roles and settled down to cook their midday meals. Osterhaus, thinking the day’s action over, rode back in the direction of his main column. Charles Woods, the division commander, was still with the rest of his command, so Walcutt was alone with his brigade.

Though major action was not expected, Walcutt’s Federals were experienced enough to at least construct minor defenses. Theodore Upson of the 100th Indiana described these entrenchments as “slight works thrown up hastily with rails,” and Arndt’s gunners had small lunettes for their two Napoleons.[7] These works were positioned “in the edge of the timber and along a slight rise in the ground, at the base of which a kind of marshy swamp formed a natural obstruction to the approach; the right and left of the position was pretty well secured by swamps.” In front of the Northerners was an open field, bisected by two meandering creeks, with a length of about 600 yards.[8]

The breastworks, though slight, and the strong nature of their positioning would soon serve the Federals handily. Coming straight at them were at least six brigades of Georgian militia and state line troops. These Confederates, the state line troops excluded, were not regular soldiers. Rather they were what was left of the male populace of Georgia—soldiers who were called up in the emergency to oppose Sherman’s march. The militia units had soldiers ranging in age from 16—60 years old. Under the command of Brig. Gen. Pleasant J. Philips the Georgians passed through the burned-out Griswoldville around noontime and continued on, looking for their foe.[9]

It was around one in the afternoon when Philip’s Georgians hit Walcutt’s skirmishers. The Federal pickets, seeing the large force in front of them, scurried back to the main works. In the ranks of the 103rd Illinois, a regiment that had apparently skirted the responsibility of digging trenches, the men threw themselves into the feverish task, seeing the odds stacked against them. The result was a “hastily constructed…small, temporary line of works.”[10]

Taking time to deploy his brigades after their initial clash with the Federal skirmishers, Philips’ brigades were finally ready to make their main advance around 2:30 PM. There are a variety of accounts stating different figures of Philips’ total strength: the Federals, perhaps predictably, overshot their estimate when one officer guessed “between 6,000 and 7,000 men.” Noah Andre Trudeau, in the definitive account of Sherman’s March, quotes “2,300-2,400 men on hand.” The Georgians were also joined by an experienced four-gun battery of Napoleons commanded by Captain Ruel Anderson. Using round numbers, Walcutt’s infantry brigade was outnumbered by two guns and a 1.5:1 infantry ratio.[11]

Map intellectual property of Benjamin H. Allen

The Battle of Griswoldville started out remarkably well for the inexperienced Georgians. Anderson’s battery of Napoleons began firing at Arndt’s section of guns, also Napoleons, and had immediate success. As the rebel guns opened up, “one of the first shells” exploded a caisson behind Arndt’s guns in a great fireball. Arndt himself was felled soon thereafter, writing, “The ball…struck my pipe in my overcoat pocket, glanced off and went through my blouse in a downward direction, then through my vest and… struck the saber belt plate, which saved my life.”[12]

Anderson’s Confederate guns also made General Walcutt a victim, striking him in the thigh with shrapnel. As Walcutt was carried from the field, command of the brigade fell to Colonel Robert F. Catterson of the 97th Indiana.[13]

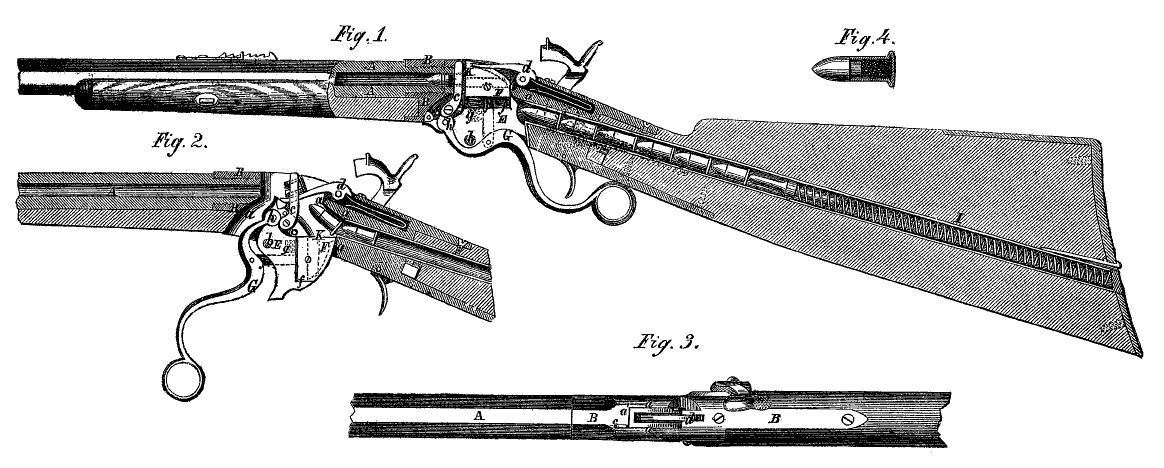

Though the Confederate artillery won the first stage of the fight at Griswoldville, as soon as Philips unleashed his brigades against the entrenched Federals the pendulum swung back to the Unionists. Though outnumbered and under heavy cannon fire, the Union infantry readied themselves and poked their rifle barrels through the rails of their defensive works. And while the seven regiments in the brigade now being led by Catterson did have the familiar Springfield and Enfield rifles, they also had repeating rifles.

By this point in the war, many Federal soldiers had saved their money and bought their own, non-regulation repeating rifles. The Spencer Rifle was in plenty of Federal hands at Griswoldville and those rifles would even the playing field. Invented by Christopher Spencer, the Spencer Rifle had a seven-round capacity that was breech-loaded all in one motion. By simply pulling the firing hammer back after each shot, the shooter was ready to pull the trigger again. Theodore Upson commented, “we had one thing that helped us greatly and that was part of our men are armed with repeating rifles which enabled us to keep up a continuous fire.”[14]

Philips’ men were torn to pieces by the near-constant volleys erupting from the rail line. Even with Arndt’s two guns driven from the field, and Walcutt cut down by shrapnel, the Union infantry was able to face off against their opponent with resolute determination. But even through the hail of bullets, the Georgian troops pressed on, finally taking cover in a ravine about 50 yards away from the Federals. From there, the Confederates made a number of desperate charges against the Union line. All of them were thrown back.[15]

As the Union soldiers continued their lively-fire, they soon realized the negative-side to their accelerated shooting: ammunition was dwindling. They doggedly fixed bayonets and continued to hold their “thin line,” until more ammunition could be brought up from the rear.[16]

Besides ammunition, support was being sent to the lone brigade as well. Hearing the firing, Charles Woods, back with his division, sent up the 12th Indiana along with two regiments of cavalry. These three regiments arrived alongside the other regiments of Walcutt’s line and thickened the works.[17]

It was evident that the Georgians were not going to break the Federal line. Retreating under the growing darkness, Philips’ men began their trek back to Macon, leaving their dead and wounded on the field. Federal firepower had won the Battle of Griswoldville.

As the Union soldiers policed the battlefield, they were horrified at the results. These men were veterans of many of Sherman’s campaigns, and they had seen their fair share of battlegrounds, but Griswoldville was different. One account wrote, “Old grey-haired and weakly looking men and little boys not over fifteen years old, lay dead or writhing in pain.” In front of the 100th Indiana, Theodore Upson wrote that “It was a terrible sight…We moved a few bodies, and there was a boy with a broken arm and leg—just a boy 14 years old; and beside him, cold in death, lay his Father, two brothers, and an Uncle. It was a harvest of death.”[18]

The casualties of Griswoldville are a testament to the nature of the battle. Officially the Confederates would report “Our loss was a little over 600, being more than [25%] of the effective muskets we had in the engagement.”[19] Walcutt’s men, on the other hand, behind their defensive works and armed with repeating rifles, suffered 13 killed and 86 wounded, for a total of 99. In other words, the Federals, outnumbered 1.5:1, inflicted casualties at a ratio of 6:1.[20]

Griswoldville was a disaster for the Georgia troops, and it accomplished next to nothing. Sherman’s March to the Sea continued unhindered.

__________________________________________________________

[1] Burke Davis, Sherman’s March (Random House, 1980), 54; Noah Andre Trudeau, Southern Storm: Sherman’s March to the Sea (HarperCollins, 2008), 158-159.

[2] Steven E. Woodworth, Nothing But Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861-1865 (Random House, 2005), 596.

[3] The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Hereafter Cited as OR) Ser. 1, Vol. 44, 82.

[4] Ezra Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (LSU Press, 1964), 534.

[5] OR, 97-98.

[6] OR, 83.

[7] Theodore F. Upson, With Sherman to the Sea: The Civil War Letters, Diaries, & Reminiscences of Theodore F. Upson, edited by Oscar Osburn Winther (Indiana University Press, 1958 printing), 137; Trudeau, 202.

[8] Woodworth, 596.

[9] William Robert Scaife and William Harris Bragg, Joe Brown’s Pets: The Georgia Militia, 1861-1865 (Mercer University Press, 2004), 4, 73.

[10] OR, 107.

[11] OR, 105; Trudeau, 203; Scaife and Bragg, 76.

[12] William Harris Bragg, Griswoldville (Mercer University Press, 2009) 130; A.F.R. Arndt, “Reminiscences of an Artillery Officer” in War Papers Read before Michigan Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, 9. http://books.google.com/books?id=SMoOAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA1-PA41&lpg=RA1-PA41&dq=Reminiscences+of+an+artillery+officer+arndt&source=bl&ots=wRW24t_7GB&sig=64JjexQ0sbNmod_f5vu4nEQmQbg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=0zhwVKDlJMaqNpyGhOAN&ved=0CCkQ6AEwBDgK#v=onepage&q=vest&f=false

[13] OR, 105.

[14] Upson, 137.

[15] Scaife and Bragg, 78.

[16] OR, 107.

[17] OR, 98; Trudeau, 211.

[18] Lee Kennett, Marching Through Georgia: The Story of Soldiers & Civilians During Sherman’s Campaign (HarperCollins, 1995), 255; Upson, 138.

[19] OR, 414.

[20] Trudeau, 214.

I was at the Griswoldville battlefield this day, at the very time of the battle, to pay respects to the fallen and remember the bravery of those who fought here.

The living history experts at Griswoldville today, dressed as Confederates, had a subsequent engagement in which they were to change into Union uniforms and burn a house up the road in Clinton! Re-enactors are engaging in increasingly compelling realism!

Reblogged this on Practically Historical.

I have been on this land many times found a few mini balls. If you look at a modern day aerial map You will see a small pond. The battle was fought on both sides of that pond .The pond was built in the 1980s. Standing at the current markers looking towards the pond about 100 yards stood the Duncan house Continuing straight down about 175 yards at the wood line you should find several pieces of fragments of cannon balls and grape shot if still their. I believe this to be the main line of defense.

Speaking of the Battle of Griswoldville. Would like to visit site. I am a reenactor. Did you get permission to be on private property if so do you remember who you contacted? Having difficulty from computer trying to follow maps of lanes of attack and compared to Ariel photos. Very excited by your summary and findings. Any help would be appreciated. Thanks Gene

My Confederate GGG Grandfather William Bussey, fought with the Georgia militia at Griswoldville. He was wounded and transported to a Union prison camp. I was hoping someone might know which Union camp was most likely to have been used for these soldiers. Thanks for any assisstance!

Great overview. I recently found an ancestor in the 100th Indiana who was at the battle.

Samuel Griswold is my GGG grandfather. I visited the battlefield for the first time last week. Very surreal experience.

My GGG grandfather was killed in this battle. He was hit with a cannonball in the back during a retreat. I recently found this out and went to the battle field and walked around for a couple hours I sat under a big old tree wondering how things went down that day. It was more moving an experience than I thought it would be. I’ve visited battlefields all over the south but this was different. To know that your own relatives died in that battle is definitely a different kind of feeling. I fell closer to him and never even knew who he was.