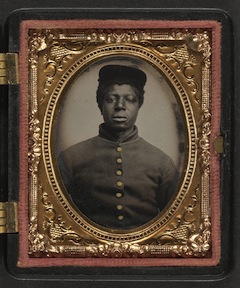

I Wish I Had Been in the Case: Portrait Photography, Federal Soldiers, and the Home Circle (part one)

Today, we are pleased to welcome guest author James Brookes. This is the first of a two-part series.

In April 1855, the English photographer Roger Fenton wrote to his wife from the Crimean Peninsula to update her on his progress in taking various photographic views of that conflict. Anxious to “get up to the front,” Fenton bemoaned a repetitive request heard from the British and French soldiers that surrounded him. “Everybody is bothering me for their portrait to send home . . . were I to listen to them & take the portrait of all comers I should be busy from now to Chrismas & might make a regular gold digging in the Crimea.”[i]

If Fenton was a subscriber to the British Journal of Photography, which is quite likely, then he might have read a series of letters by the American engineer Coleman Sellers, which recognised that his hypothetical Crimean musings were being proved true in the American Civil War. In February 1862, Sellers stated that “with the professional operators the war has been quite a source of profit.”[ii]

In May, Sellers observed that a New York photographer was “driving a brisk business at the camps below Washington . . . making fifty dollars per day with the ambrotype alone.”[iii] The American innovator reported, “What a blessing it is that they who go to war can not only leave behind them their images, but take with them a semblance of those they leave at home!” thus recognising the first instance of such a tremendous outpouring of portrait photography in U.S. military history.[iv] These letters confirm that portrait photographs had gained an intrinsic place in the Federal soldier’s personal inventory and within the domestic sphere of the home-circle. Less sentimentally, the cultural shift established that mobilisation served as the perfect catalyst for the portrait photography business.

The Civil War occured within a relative, constant proximity to U.S. centers of photography such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. The photographic business in the North was growing at an unprecedented rate due to the popularity of portrait mediums resulting from the wet collodion process and the albumen print. Widespread access to tintypes, the carte-de-visite, and ambrotypes in the years prior to and during the conflict had ingrained the photographic portrait as a significant medium of self-representation within the northern population. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., writing in The Atlantic Monthly in 1863, noted that “card-portraits” had become “the social currency, the sentimental ‘green-backs’ of civilisation, within a very recent period.”[v] A year later John Towles, editor of Humphrey’s Journal, boasted that “Everybody keeps a photographic album”.[vi] The established popularity of the photograph by the 1860s era ensured these portraits were prolific objects of emotion and memory in American culture during the war.

E. W. Locke’s Three Years in Camp and Hospital, largely a history of “the common soldiers [rather] than the officers” due to the author’s constant proximity to “the working class of [the] army,” illuminates the significance and accessibility of the portrait.[vii] Writing of what he deemed one of “the most useful of the camp-followers,” the “picture-maker,” he noted. “Often the picture taken in camp is the last and most precious memento the home-circle has of him who sleeps they know not where. These mementos exist in every town and hamlet in our country.”[viii]

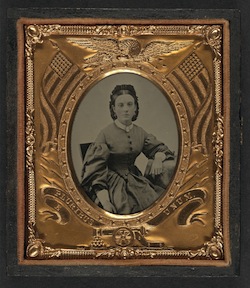

In terms of the soldier’s departure, Wilbur F. Hinman, author of the partially-fictionalised Corporal Si Klegg and His “Pard.”, wrote of the ways in which women would prepare their dearest. His short description encapsulates the desire of family members to ensure that the soldier would not suffer too greatly during his absence. Annabel, Si’s significant other, makes him a pair of slippers, stitches his name onto “half a dozen nice handkerchiefs,” and fashions a “fancy bookmark” so that he will not lose his place in his bible. The final preparation for Si’s parting is to visit the photographer to sit for her picture, “This she had enclosed in a pretty locket, with a wisp of her hair,” that could be worn around his neck. Concluding on these intimate arrangements, Hinman, himself a four-year veteran of the 65th Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry, notes, “All of these things helped to make Si happy.”[ix]

As a text with the objective of representing the common soldier’s experience as a whole (“[Si and his pard] are imaginary characters – though their prototypes were in every regiment”), Hinman’s description offers an interesting observation regarding the volunteer’s departure.[x] Although slippers, nice handkerchiefs and fancy bookmarks are perhaps excessively extravagant for a soldier on campaign (though by no means less important as sentimental gestures), the locket contains and protects a visual likeness of Annabel and a tangible remnant of her physical form, and allows these dear mementos to be worn closely around Si’s neck. Hinman’s desire for this text to be a universal story of the Federal volunteer suggests the widespread use of such tokens as mechanisms to bridge the divide formed by the soldier’s parting. As a post-war memoir, the account establishes that these mementos formed part of the enduring legacy of the citizen-soldier’s Civil War experience.

To be continued….

* * *

James Brookes studied American Studies at Great Britain’s Nottingham University as an undergraduate in 2009, spending a year abroad in the U.S. at the College of William and Mary. His undergraduate dissertation was an examination of the importance of the tintype portrait to Civil War soldiers, and his MRes thesis is now expanding on the topic by studying the relation of all forms of portrait photography to Federal soldiers in particular. He plans to write his PhD thesis on various forms (paintings, sketches, cartoons) of visual culture created by the rank-and-file during the war. James has also engaged in Civil War living history in both Europe and the United States, sometimes acting as an assistant to the UK’s only itinerant 19th century historical photographer. Visit his blog, Gone For Soldiers.

* * *

[i] Roger Fenton, ‘Letter to Grace Fenton, April 4/5, 1855’, in Helmut Gernsheim, The Rise of Photography: 1850-1880, the Age of Collodion, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), pp. 93-5.

[ii] Coleman Sellers, ‘Letter of February 1, 1862’, published in the British Journal of Photography 9 (March 1, 1862), p. 95, quoted in Keith F. Davis, “A Terrible Distinctness,” in Sandweiss, ed., Photography in Nineteenth-Century America, p. 142.

[iii] Sellers, ‘Letter of May 25, 1862’, in British Journal of Photography 9 (June 16, 1862), p. 239, in ibid., p. 143.

[iv] Sellers, ‘Letter of August 25, 1862’, in the British Journal of Photography 9 (October 1, 1862), p. 375, in ibid., p. 143.

[v] Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., in ‘Doings of the Sunbeam,’ in The Atlantic Monthly 12, (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, July 1863), p. 8.

[vi] John Towles, “Photographic Eminence,” Humphrey’s Journal 16 (June 15, 1864), p. 93, in Barbara McCandless, “The Portrait Studio and the Celebrity,” in Martha A. Sandweiss, ed., Photography in Nineteenth-Century America, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 1991), p. 62.

[vii] E. W. Locke, Three Years in Camp and Hospital, (Boston: Geo. D. Russell & Co., 1870), p. iv.

[viii] Ibid., p. 300.

[ix] Wilbur F. Hinman, Corporal Si Klegg and his “Pard.” (Cleveland, OH: The N. G. Hamilton Publishing Co., 1900), p. 38.

[x] Ibid., p. v.

…and how priceless those images are for us with ancestors in the war. Seeing their pictures brings life to their stories!