The Art of Hiding Personal Effects, Part One: Slaves

As Union forces marched south under Sherman, wreaking havoc across several Southern states, stories of Northern atrocities spread. It’s hard to say which stories were true, and which were fanciful creations that played on Southern sentiments, like some of those written for the Confederate Veteran in the 1890s and early 1900s; however, numerous journal entries and letters from 1864-1865 attest to unfair treatment of Southern residents and their property under Sherman.

Southern cities and homes were pillaged, and many families were often left starving. As he marched through the South, Sherman’s plan involved breaking the Confederate backbone by breaking its constituents. It worked, creating deep resentment among Southerners which continued throughout the years after the war. This three part series will illustrate the innovative ways families attempted to protect their property from Union foes as Sherman’s troops forged a path of destruction through the southern states of Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina in December, January, and February of 1864-1865.

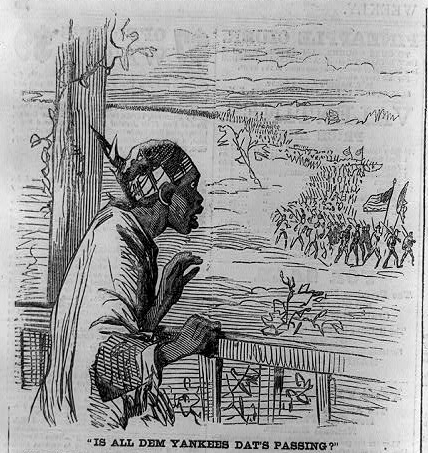

Hiding personal items from Union foragers became a common practice throughout the South as Sherman’s troops marched from Atlanta to Savannah, followed by a march through the Carolinas in early 1865. Under Special Order No. 120, soldiers were allowed to liberally forage among the countryside for food, and some troops extended this to foraging through households, slave cabins, and other outbuildings. Families hid jewelry, silver, food, and in some cases, slaves. Up until January 31, 1865, when Congress passed the 13th amendment abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude, slaves were considered property, and in the minds of most Southern slave owners, slaves were property to be protected and guarded.

Some Southerners worried about the Federal government confiscating their enslaved property and enlisting them in the Union army, while others worried their slaves would seek refuge just over the picket line. After the start of the war, some owners thought about sending their slaves to a refuge, in case their town or city was invaded or captured by the Union. The Watts family of Roanoke County, Virginia, was one of these families. In several letters in 1862, friends and cousins urge the Watts family to follow suit with other slave owners in the area and purchase a portion of land in Henry County, “securing a place of safety for some of their negroes.”[i] One member of the family, when discussing this proposal, wrote, “I must confess the idea of having a place to send the negroes strikes me as a good one. They have gone off with so little hesitation whenever the enemy comes, it would be well to secure a few.”[ii] She continued, “Mr. Carr says [the slaves] behaved horridly in Kanawha and he seems greatly disgusted with the perfidy. At his Brother’s, they got out the carriage and occupying it, drove off in the day time, taking with them whatever they chose.”[iii] By moving slaves to a separate piece of property, slave owners hoped it removed the temptation of freedom, placed them out of the way of the Union march, and kept up the pretense of a normal life before the war.

While many slaves escaped to the Union through various means, some African Americans stayed loyal to their owners, and felt betrayed when troops came pushing through their cabins, looking for clothing and other valuables, as well as sometimes being forced to enlist for the Union. With the issue of Special Field Order No. 16, Sherman forbade officers to enlist African Americans on their march south; however, some officers obtained orders against Sherman’s wishes, and continued the enlistment of African Americans throughout occupied Georgia.[iv] Dolly Sumner Lunt chronicled her mishaps when Union soldiers arrived at her doorstep in November of 1864. She worried mostly about her valuables and her house, thinking little about her slaves until she found that soldiers “were forcing [her] boys from home at the point of the bayonet.”[v] She attempted to aid them in their flight from the soldiers; telling one to hide in her room, hoping etiquette would keep them out of a female’s private quarters. She urged another to escape through a window, only to be caught on the other side. Some acted sick or hurt, while others tried to hide under the beds or ran to the woods surrounding the plantation. In the end, the majority of her African American men were bundled off, with the Union invaders “cursing them and saying that ‘Jeff Davis wanted to put them in his army, but that they should not fight for him, but for the Union.’”[vi]

Hiding slaves was one of the more difficult tasks in protecting property. The cases of Southerners moving their slaves to a separate location, as well as cases of Union foragers forcing enlistment, were few and far between. The case studies of the Watts family and Dolly Sumner Lunt illustrate that despite the war, Southerners still felt compelled to protect their way of life by hiding their slaves. Check back next week for a post on how Southerners protected their valuables!

[i] Alice Mathilda Watts Morris to William Watts, 5 April 1862, Watts Collection, History Museum of Western Virginia, 2007.32.136.

[ii] Letitia Gamble Watts Rives to William Watts, 24 October 1862, Watts Collection, History Museum of Western Virginia, 2007.32.146.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] William T. Sherman, “War is Hell!”: William T. Sherman’s Personal Narrative of His March through Georgia, ed. Mills Lane (Savannah: The Beehive Press, 1974), 144-146.

[v] Dolly Sumner Lunt, A Woman’s Wartime Journal, 24

[vi] Ibid., 25

Bibliography

Watts Collection. History Museum of Western Virginia, Roanoke.

Sherman, William T. “War is Hell!”: William T. Sherman’s Personal Narrative of His March through Georgia, edited by Mills Lane. Savannah: The Beehive Press, 1974.

Lunt, Dolly Sumner. A Woman’s Wartime Journal. New York: The Century Co., 1918. http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/burge/lunt.html

“Is all dem Yankees dat’s passing?” Print. 1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/89706319/ (accessed December 15 2014).

Reblogged this on Poore Boys In Gray.

From the diary of Noah Kumler, 17th OVI (sometimes difficult to read) on orders to forage:

Sept 3rd 4th & 5th 1864

The 14th A.C. Laid Still

at Jonesboro, Ga. Guarding

the Wagon Train and done a

lot of foraging …

Oct 12 th Wed. 1864

We marched about 18 miles

North west. and camped about

3 miles off Rome Ga…

Oct 16 th Sun

Marched Down the Mountain into

Snake Creek Gap The rebels Block

aded the Gap by Falling Timber

across the road about 3 m after we

got the the gap Shermans army

Marched in 3 Colums along a road

Went into camp at 3 ocl and got orders

to forage which was plenty

Further foraging:

Who were busy Caring rails and

Building Baricades and expecting

Wheelers to make a dash on them

any minuit. But everything was

quiet but Slight Skirmish with the

out post Cavalry and Foragers

It’s so interesting to read the nonchalant way Noah mentions the foraging while their marching! Thanks for including it!

M Kumler.. I am a Coomler… My G grandfather was named after Sherman …. because his Dad was on the Shermans march to the sea. John Sherman Coomler