The Battle of Portland Harbor (Conclusion)

Part One can be read here. Part Two can be read here.

It had been a hectic morning on June 27, 1863. Under the cover of darkness, rebel privateers under the command of Charles Read first jumped aboard the Caleb Cushing, a revenue cutter tied-up port within Portland, Maine. Read’s men captured the small crew aboard the cutter and then started to make their way out of the harbor, but were stalled due to small winds that barely caught the Caleb Cushing’s sails. At first light, discovering that the cutter had been captured, Portland’s fortresses and garrisons were abuzz, and about an hour after first learning of the Caleb Cushing’s capture, a small armada of ships steamed after Read’s prize.

By the time that the Federal ships caught up to Read, the Confederates had managed to only get about 15 miles out of the harbor. Seeing the oncoming Federals, Read decided to fight it out. Except the Georgian-born Lieutenant Dudley Davenport, in temporary command of the Caleb Cushing at the time of its capture, was not cooperating.

Aboard the Caleb Cushing Read’s men found enough shot and powder for about ten discharges from the large 32-pounder. This would not be nearly enough to fight off the oncoming vessels, but Davenport steadfastly refused to give up the location of the keys that would open the Caleb Cushing’s powder magazine. Deep in the hold of the Caleb Cushing were almost ninety rounds of solid and case shot with accompanying powder stores and yet, for all he threatened and roared, Read was not able to coerce Davenport into giving up the keys.[1]

With his limited supply of shot and powder, Read chose nonetheless to fight. Heaving to, and at a range of about two miles, the rebels aboard the Caleb Cushing fired their first round from the 32-pounder. The shot roared across the waterline; first the Federals saw a puff of white smoke and then, a moment later, the deep rumble of the cannon. Aboard the Forest City, the closer of the ships, Nathaniel Prime of the 17th U.S. was hesitant to fire back, and even if he had wanted to, his subordinate recorded that “my pieces were too light at that distance, and I did not want to wish to show their small size….”[2]

Prime also had to reckon with the skittish civilian pilot of the Forest City. As more shots rang out from the Caleb Cushing, the rounds bounced along the water like skipping stones. Though none of the shells struck, the Forest City was completely unarmored; a single round into one of its paddle wheels would be catastrophic. With little recourse, the Forest City hung back, waiting for the Chesapeake, which was speedily chugging up to the scene.

While the Chesapeake was armed similarly to the Forest City in terms of cannon, it at least had some semblance of protection. Earlier in the morning, as the 7th Maine and citizens piled aboard, someone had had the frame of mind to throw against the sides of the Chesapeake about “50 bales of cotton for barricades.” Though not much, the cotton bales were better than the entirely unprotected Forest City.[3]

While Read fired more shots from the 32-pounder, still not hitting anything, the Chesapeake and Forest City pulled up alongside each other. Now only about a mile separated the two Federal ships from the Caleb Cushing, which was quickly running out of shots because of Davenport’s tenacious refusals to Read’s demands. Picking up steam, the Chesapeake made its way towards the Caleb Cushing¸ evidently with the intent of ramming the captured cutter.[4]

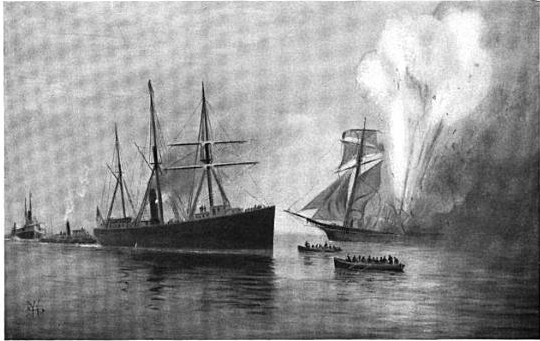

As the Chesapeake rushed ahead, Charles Read knew he was running out of options. The 32-pounder fired one last time, scattering a load of grapeshot across the water in what was entirely a final symbol of resistance. With his largest asset now useless, Read gathered the Caleb Cushing’s captured crew on deck and herded them and his prize crew into small rowboats. Before abandoning the cutter, though, a slow match was set on fire and the flames began to crackle around the ship.

Aboard the Forest City one officer armed with a set of field glasses spotted the ever-growing flames and the curling black smoke. “Expecting every moment to see her blown to atoms,” the officer wrote, “I advised the [ship’s pilot] to bear away…”[5]

With Read and his men in one boat, and the Caleb Cushing’s crew in another, the two were soon scooped up by the Forest City and the Chesapeake, respectively. Aboard the former a witness wrote that the rebels surrendered by “frantically displayed white handkerchiefs and masonic signs…” though Regulars aboard the Forest City were not about to take any chances. One rebel wrote that the soldiers “had their muskets aimed directly at us, as if about to fire…”[6]

As Read’s men were captured and the Caleb Cushing’s crew liberated, the revenue cutter exploded. After burning for only a few minutes, the flames reached the powder hold, estimated by one officer to contain about 500 pounds worth of powder, sometime around 2:00 PM. At first there was a bright flash, and then, a moment later, a “fearful explosion,” which made the cutter almost instantly “[disappear] from our view.” A rebel added with more detail that there was a “terrific explosion that shook the little fleet standing by, and caused a disturbance on the surface of the sea. The whole deck of the vessel seemed to fly upward, and a burst of flames and vast column of smoke rose from her shattered hull. Fragments of iron, blackened timbers, bits of plank and spar, and innumerable cinders flew out of them and fell into the sea around…”[7]

(Image from “The Rudder”, Vol. 16.)

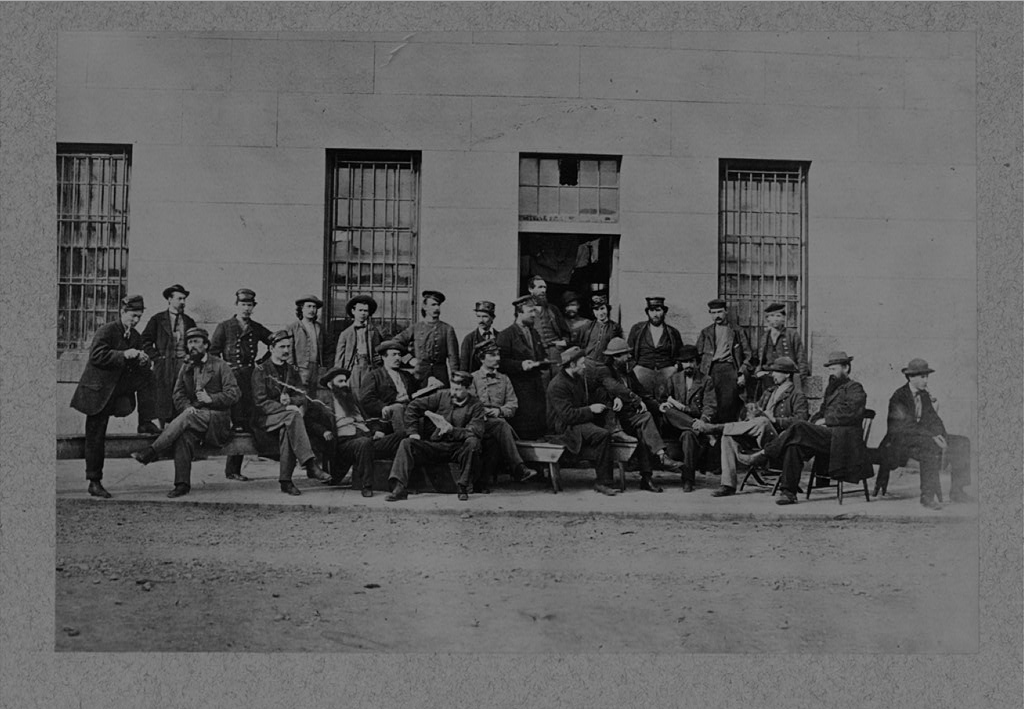

The explosion of the Caleb Cushing and its rapid sinking proved to be the climatic finish to the Battle of Portland Harbor. The Archer, Read’s captured prize that he had sailed into Portland Harbor the day before, was nearby and trying to slink away but the Forest City quickly caught up and, with one shot fired across its bow, convinced the smaller ship to surrender. The Federals returned to Portland and Read with his men were temporarily imprisoned in Fort Preble, the headquarters for the 17th United States Infantry.[8]

Read did not say in Portland for long, however. Major George Andrews, commanding the Regulars at Fort Preble, wrote to his superiors, suggesting that the rebels be moved away from the harbor because of the “present excitement.” Andrews elaborated, “I would respectfully suggest that the prisoners be sent from here as quietly and expeditiously as possible, as I do not think it safe here for them to be placed in the custody of the citizens….”[9] Agreeing with Andrews, higher commands arranged for Read and his rebels to be moved to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor a short while later.[10]

Almost as quickly as it had begun, the Battle of Portland Harbor was over. Read’s adventure, from leaving the CSS Florida off the coast of Brazil to his capture off the coast of Maine, lasted 52 days. He captured or destroyed close to twenty ships, including in a grand finale, the Caleb Cushing. Read would remain as a prisoner at Fort Warren until being exchanged in September, 1864.[11]

As far as the Federals were concerned, their military victory in capturing Read, albeit at the expense of the Caleb Cushing, came almost entirely because of the quick actions of the custom collector, Jedediah Jewett. Jewett’s initiative and rapid-fire directions was what, ultimately, captured the rebel privateers. Speaking of Jewett and Mayor Jacob McLellan, who armed citizens at the state arsenal, one man wrote, “life was worth living that morning if only to see the tremendous energy of those two men.”[12]

The Civil War had come to the coast of Maine, and, then, in the blink of an eye, was gone again.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion,Ser. 1, Vol. 2, 329 (hereafter cited as OR Navies).

[2] OR Navies, 328.

[3] OR Navies, 323.

[4] OR Navies, 325.

[5] Ibid.

[6] OR Navies, 326; Winfield M. Thompson, “A Confederate Raid”, in The Rudder, edited by Thomas Fleming Day, Volume 16, 1905, 246.

[7] OR Navies, 326; Thompson, 246-247.

[8] OR Navies, 326.

[9] OR Navies, 327.

[10] Charles L. Dufour, Nine Men in Gray (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 147.

[11] Register of Officers of the Confederate States Navy 1861-1865 (Washington: Government Printing Press, 1931), 161.

[12] Members of Bosworth Post, Portland Soldiers and Sailors: A Brief Sketch of the Part they took in the War of the Rebellion (Portland: B. Thurston & Co, 1884), 33.

Interesting and exciting story ! Thanks for posting.

Thanks for commenting, David. I’m glad you enjoyed the posts.

On Chebeague Island, in Casco Bay some ten miles from Portland, there is a grave of an “Unknown Soldier” that washed ashore some time after the Battle of Portland Harbor. Local legend has it that he was a confederate soldier from the Caleb Cushing. Could this be possible?

Hi David, thanks for commenting. While a good story, I think it is exactly what you said, a local legend. When I was doing research on this series the only mention of any casualties I came across was one man, Jacob Gould, who was accidentally shot by someone being careless with a musket. Before blowing up the “Caleb Cushing” Read got his crew off and surrendered to the Federals, so I don’t believe any Confederates were still on board when the ship exploded. Thanks again for commenting.

Really enjoyed reading this…Jacob McLellan was my great, great grandfather and the story has been repeated in the family for as long as I can remember….Thank you!

Hi Connie,

I’m glad you enjoyed the series and thanks so much for commenting.

Amazing! I’m currently doing a research project based on old Portland graveyards. When searching i found an interesting grave of Captain Green Walden. I’d heard this story prior and was amazed to find out that not only was the previous captain of the Caleb Cushing. But the battle of Portland harbor occurred 3 years after his retirement in 1860, and, right on the coast of his home in Cape Elizabeth.

I was curious to know if you would have any information on the prior engagements of the Cushing while under his command (prior to 1860). Your articles were very well written and informative, As well as the use of first-hand accounts, which must have been hard to find, at least, i’ve had no luck. Maybe I’m looking in the wrong places!

I look forward to a possible response,

Adrian.