“One of the most deplorable incidents”

On March 21, 1865, one of the last actions of the battle of Bentonville—which, in turn, was the last major engagement between Confederate forces and Union soldiers under William T. Sherman in the Western theater—cut short another young life.

Thousands of sons before him and still hundreds more young men would lose their life in the American Civil War.

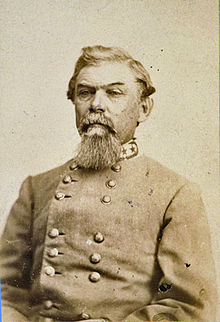

However, the death of Willie Hardee, the only son of Confederate General William J. Hardee, was both tragic and heart-rending. And not just for his family and doting father but to his fellow soldiers.

The quote used for the title of this blog post comes from the letter of Colonel W.D. Pickett who had firsthand knowledge, according to his introduction in the January 1916 edition of the Confederate Veteran of the late Willie Hardee.

Willie Hardee had tried to join the 8th Texas Cavalry in 1864 when the unit was in Georgia. The hardened veterans took the younger Hardee back to his father who probably admonished his impetuous son for running away from school. However, the 16-year old would not be denied a chance to fight for the Confederate cause.

The younger Hardee did spending some time in what the lad considered dull service roles which consisted of being on the staff of his father and then also as a junior officer in an artillery battalion in early February 1865. On the movement from Averasboro to Bentonville, the younger Hardee came across his former, albeit brief, comrades in the 8th Texas Cavalry. He returned quickly to his father and begged to be allowed to join the cavalrymen.

With words he would probably regret, the elder Hardee gave his consent, letting the officer in the Lone Star State unit, “swear him into your service in your company as nothing else will satisfy.” With that one sentence, the 16-year old was a Texas Ranger.

On the afternoon of March 21, the Texas cavalrymen, with Hardee in tow, was called to help repel Union General Joseph Mower’s advance, specifically to save the Mill Creek Bridge, a lifeline for the Confederates.

During that assault, one of the last offensive maneuvers of the Confederates in the last major engagement of the war in that particular theater, the bravery of the Texans and the Tennessean cavalry that charged with them were on full display.

General Hardee actually issued the specific orders to the 8th Texas and 4th Tennessee Cavalry who charged screaming and hollering into the two brigades of Union infantry that Mower had on this portion of the field.

As Hardee moved to funnel infantry into the assault, one of the Federal soldiers fired a shot at the quickly advancing Confederate cavaliers. This fateful bullet slammed into the chest of the younger Hardee, almost throwing him from his saddle. Luckily, for the young recently mustered in Texas Ranger, a fellow soldiers was able to keep him on the horse.

Unbeknownst to his father, who was currently celebrating the repulse of the Union flank attack, the mortally wounded Willie Hardee and his fellow soldier made their way back to Confederate lines.

The younger Hardee was brought toward his father, whose elation quickly turned to horror and despair. There was his only son, desperately wounded. Willie Hardee was placed on a stretcher and under the orders of his father, transported to the home of a niece, where Willie’s mother and sister were currently staying. Willie Hardee would make the journey to Hillsborough, North Carolina, where the relative’s homestead was.

Two days later, on March 23, 1865, the teenager died.

Two days later, on March 23, 1865, the teenager died.

In a fitting epitaph for many a parent whose young son was lost fighting for a cause in the American Civil War, the Kentuckian, Pickett concluded his piece on Willie.

“It was sad indeed that in this last battle of the war fought east of the Mississippi’ father and son were forever separated by the enemy’s bullets.”

Many a father and many a son could relate to the grief of the Hardee family on March 23, 1865.

Way too many.