Wilderness and Ward and Ulysses S. Grant

At the end of April 1885, Ulysses S. Grant knew he was dying. In fact, he had almost died earlier that month. Throat cancer ravaged him, and in late March, his condition collapsed so severely that it nearly killed him. Only extraordinary measures by his doctors revived him. “The truth is,” one of Grant’s close friends admitted, “the disease has gotten away from the doctors.”

At the end of April 1885, Ulysses S. Grant knew he was dying. In fact, he had almost died earlier that month. Throat cancer ravaged him, and in late March, his condition collapsed so severely that it nearly killed him. Only extraordinary measures by his doctors revived him. “The truth is,” one of Grant’s close friends admitted, “the disease has gotten away from the doctors.”

But in the weeks after, a revived Grant celebrated the 20th anniversary of his April 9 victory at Appomattox Court House. “One of [Grant’s] sons had a presentiment that his father would not survive this day,” wrote Grant’s one-time aide, Adam Badeau; “but it would have been hard to have General Grant surrender on the anniversary of his greatest victory.”

Weeks after that, on April 27, Grant celebrated his sixty-third birthday: his last, as it would turn out—a probability he and the anxious nation were all keenly aware of. “The dispatches have been so numerous and so touching in tone that it would have been impossible to answer them if I had been in perfect health,” Grant gratefully acknowledged in a public statement

These occasions served to buoy him even as the cancer ate him away. He had deteriorated rapidly since his diagnosis in October—a process no doubt hastened by the strain of his financial collapse the previous May. His business partners, Ferdinand Ward and James Fish, had swindled him and left him destitute. Worse, perhaps, the proud general felt his good name had been dishonored. “[T]he wound was eating into his soul,” Badeau wrote. “The sorrow was a cancer indeed.”

The one-year anniversary of that financial disaster loomed large in Grant’s mind as May 1885 dawned. But so, too, did the anniversary of the battle of the Wilderness, which opened the spring Overland Campaign in 1864. Grant’s “no turning back” policy eventually led to him to Appomattox. The Wilderness had been a game-changer.

So as May 1885 peeled open, these two conflicting memories vied for Grant’s spirit. Add into that what must have been bittersweet emotions in the wake of his birthday, not to mention the constant pain he endured from his cancer, and one can start to imagine how Grant might have felt 130 years ago today.

Grant’s self-awareness about his terminal condition must have added deeper resonance to his reflections. “I am conscious that I am a very sick man,” he told one visitor just before his late-March plummet.

Most of us don’t have the same acute awareness of our own mortality that Grant had. Most of us don’t get the kind of advance notice about our deaths that Grant had, either. He knew he had a looming deadline.

Grant could be notoriously stoic, so we don’t know exactly how he felt that day—but we do know what he did. That, in turn, gives us some clue as to how he felt.

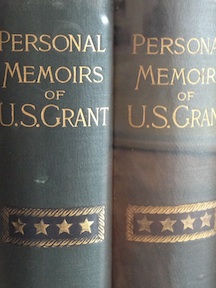

Grant had begun writing his memoirs months earlier, and although he was losing his personal war of attrition, he kept pen to paper, sometimes writing as much as ten thousand words a day. “I think his book kept him alive several months,” remarked Grant’s publisher, Mark Twain.

As May 1885 began, we know Grant ultimately turned toward the Wilderness and away from Wall Street, choosing to focus on the high rather than wallow in the low. His chapter about the Wilderness in his Memoirs is one of the book’s outstanding sections; the failure of Grant & Ward, meanwhile, didn’t merit any written record by him at all, anywhere. He certainly groused about his former business partners. “He never relented in his bitterness to these two men,” Badeau said.

But he never wrote about them.

It was the Wilderness that ultimately captured Grant’s attention. It was the Wilderness he wanted to be remembered for—and thus what he wanted to remember.

And thus, he wrote. He had started his Memoirs, and there would be no turning back.

He had fewer than sixty days to go.

Well done, Chris. I think you captured Grant’s feelings that month quite well.