Had He Lived

Every Memorial Day I give a program reflecting on the soldiers killed during the Breakthrough. There are dozens of compelling stories from which to choose for the Federals, but I have only been able to identify photographs or backstories for a handful of Confederates. It happens when one side is charging with fixed bayonets under fire across half a mile of open ground and the far-outnumbered defenders surrender in mass just minutes after their works are breached. Thus I’m constantly working with the same couple of southern casualties every year. One such soldier has a quote attached to him that I always struggle to unpack.

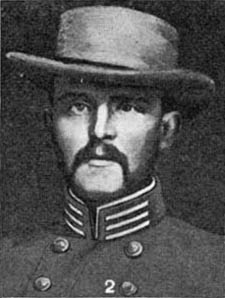

William Thorne Nicholson was born July 31, 1840, in Halifax County, North Carolina. The son of a prominent planter, William graduated with distinction from the University of North Carolina in 1860. He enlisted into the 37th North Carolina Infantry on November 20, 1861, and was appointed adjutant. The next December he was promoted captain and the following year served as judge advocate in Cadmus Wilcox’s division court. “He is a most gallant officer, and is said to be the best Judge Advocate in the army,” declared a colleague.

Nicholson then commanded the sharpshooter battalion of James Lane’s Brigade during the 1864 Overland Campaign. According to a member of that organization, Robert E. Lee called upon Wilcox to provide a man for a hazardous scouting mission to determine the flank of the Union line on May 12th, while combat raged at Spotsylvania’s Bloody Angle. Wilcox selected Nicholson.

“Captain, I am sending you on a dangerous mission, and I leave it to your discretion whether to go or not,” stated Lee, “but the fate of my army depends upon it, and for God’s sake don’t lose any time.” Nicholson accepted the mission and reported back with his findings. The division used that intelligence to direct their counterattack, buying time for Lee to establish his secondary line at the base of the “Mule Shoe” salient.

During later combat at Spotsylvania, Nicholson suffered a severe gunshot wound in his right shoulder but returned to his regiment that summer at Petersburg.

On March 25, 1865, William’s brother Edward was killed in the desperate charge against Fort Stedman. Eight days later, William was killed during the Breakthrough. Family tradition states that he had an approved leave in his pocket, but he would not leave his men on the eve of battle.

A comrade wrote of the officer: “We had fought upon twenty odd battlefields together, and it was my privilege and duty in the heat of battle, while receiving instructions from him, to watch him closely, and in all of these conflicts, no matter how trying the circumstances, never saw him lose his balance. He was a man ‘born to command men.'”

Here’s where things get dicey. Lieutenant Octavius Wiggins, who provided the above eulogy, went on to provide another statement that brings pause for consideration: “Had he lived he would have proved a great factor in adjusting political affairs during reconstruction days.”

Wiggins meant that as a compliment when he wrote his brief regimental history, published in 1901, but what are we to make of it now–knowing what we do about the enduring scars of southern resistance to Reconstruction?

Sources:

‘Warren.’ “North Carolinians in the Recent Battles.” Raleigh Weekly Confederate, June 8, 1864.

Wiggins, Octavius A. “Thirty-seventh Regiment.” Walter Clark, ed. Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, Volume 2. Goldsboro, NC: Nash Brothers, 1901, 673.

Nowadays it gives one pause, doesn’t it? Lots of ways to interpret just what “a great factor in adjusting . . .” could have meant.

The Confederates should’ve been put out of their misery.

Edward…hoping the following might add to the Confederate side of your Memorial Day Program. My great-great grandfather (John Pitchford) and his brother (Robert Pitchford) were privates in the Madison (Mississippi) Light Artillery, Poague’s Battalion. On 2 April 1865 the battery was commanded by Lt. John Yeargain and placed in position at Lee’s Headquarters. During the Federal attack, Robert was seriously wounded in the leg, taken prisoner and later died from complications due to the amputation. He is buried in the family cemetery in Warren County, North Carolina. He performed his duty to the very end. Other than your book and A. Wilson Greene’s account in “The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign”, do you know of any other publications that give detail accounts of the fighting that took place around Lee’s Headquarters on 2 April?

Thank you for sharing James. I can’t speak for Will but I know I used Poague’s reminiscences as the basis for my research on the Confederate perspective during that combat. They are published as Monroe F. Cockrell, edited “Gunner with Stonewall: Reminiscences of William Thomas Poague (Broadfoot, 1989).

Perhaps Edward Alexander’s information from family verbal legends could be expanded if more holders of such family stories had a more centralized home. Being a couple of generations from the family stories and not being trained in historical research, I had to start with some cryptic factoids to see who was who and what happened to our family members who fought in the war, Remembering stuff and comments like “Brothers walked 20 miles to sign up together and they were both killed in the same battle”. Using confederate records in general, and federal war records, Doctor reports, capture records, City point hospital records.{Hopewell, Hospital ship “State of Maine” death report hospital records District of Columbia, A handwritten letter to a girlfriend, mention in a 1901 article in an Atlanta, newspaper. The brothers were Winston and William Meredith of Tunstalls,Station, new Kent County, VA. I wrote it up for the New Kent Hist Soc., but have no clue as to a good place to send it. They were taken into Crutchfields Brigade and fought at Sailors Creek. .