Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: Hood’s Protest and Howe Avenue

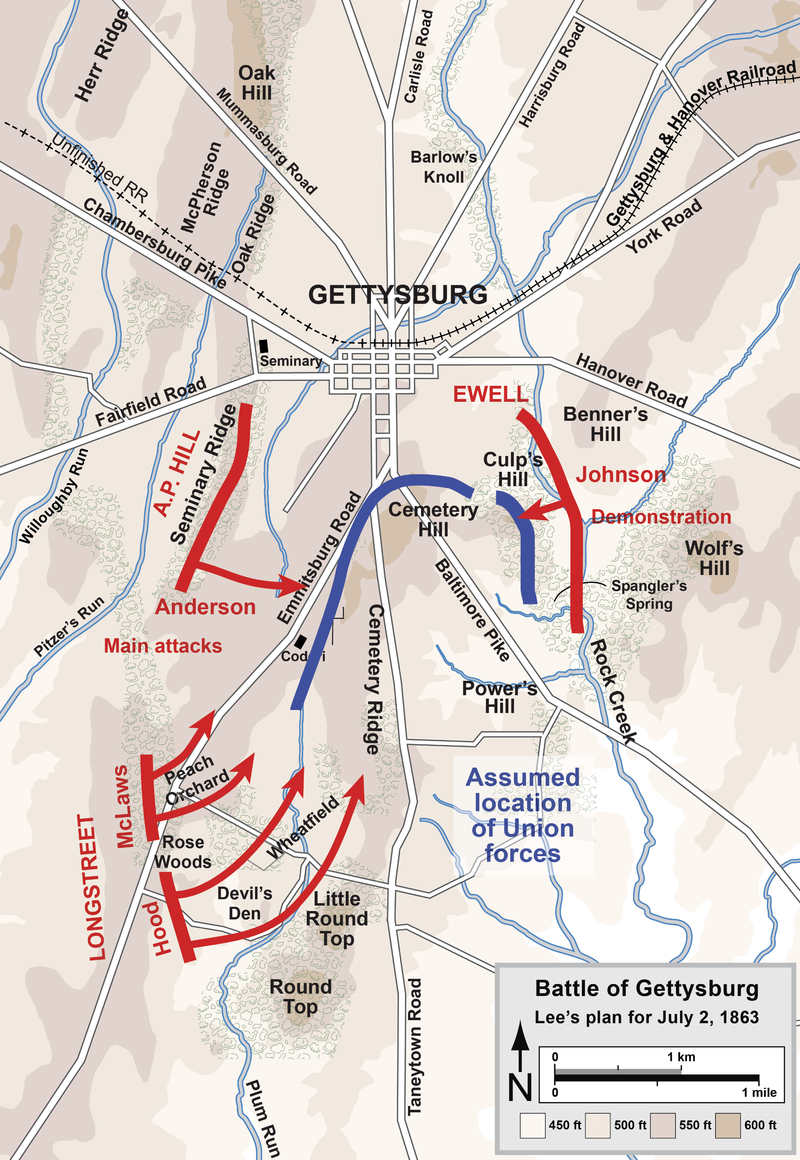

The Confederate offensive at Gettysburg on July 2nd was supposed to start much closer to the now-famous Peach Orchard than it actually did. Prior to cresting Warfield Ridge, one of the future jumping-off points for the Confederate offensive, First Corps commander James Longstreet was very active. Riding up to division commander Lafayette McLaws, the Lieutenant General asked “How are you going in?” McLaws replied, “That will be determined when I can see what is in my front.” Longstreet claimed that: “There is nothing in your front; you will be entirely on the flank of the enemy.” McLaws responded, “Then I will continue my march in columns of companies, and after arriving on the flank as far as is necessary will face to the left and march on the enemy.” Longstreet closed by saying, “That suits me,” and rode away.

Longstreet then ordered Joseph Kershaw, who was commanding his corps leading brigade, to “advance my brigade and attack the enemy…turn his [the enemy] flank, and extend along the cross-road [Wheatfield Road], with my left resting toward the Emmitsburg Road.”

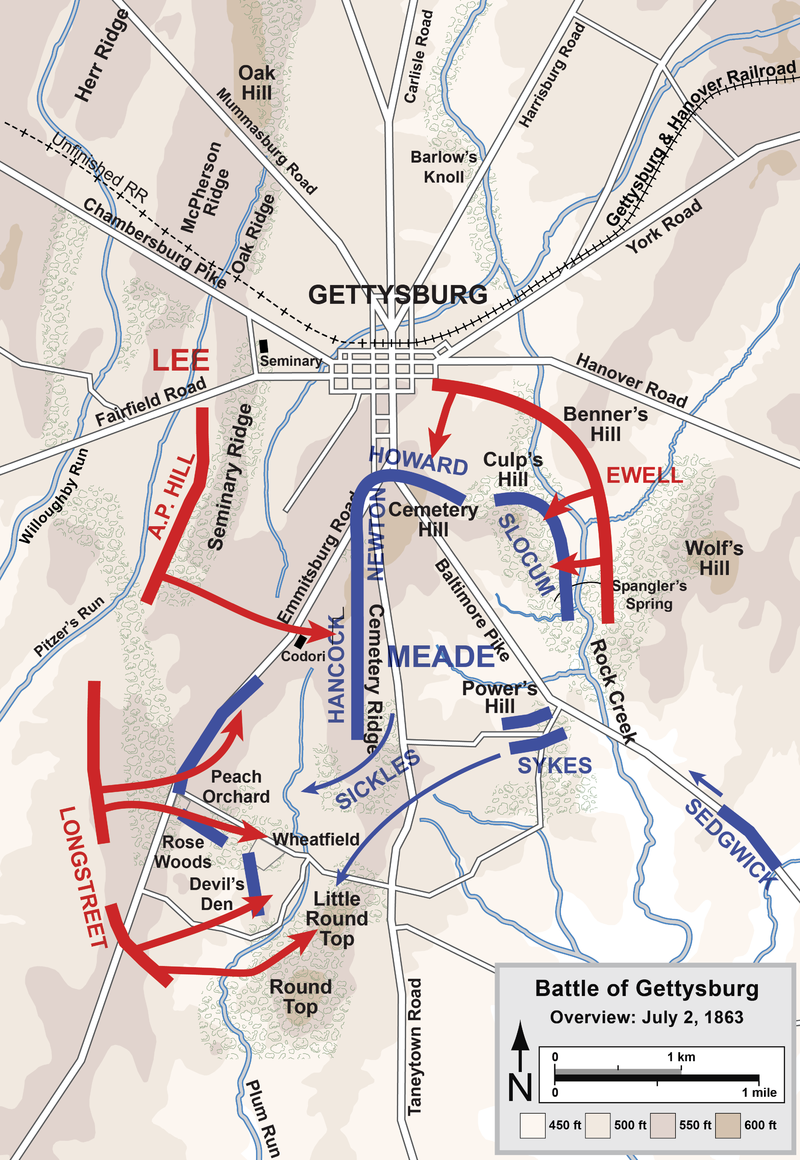

None of this was possible. Daniel Sickles Federal 3rd Corps forward movement completely threw off the nature of Lee’s offensive, and Longstreet’s orders to Kershaw. Neither McLaws nor Kershaw could move across the Emmitsburg Road perpendicularly, while enveloping the enemy left. The Peach Orchard ahead was filled with Federal infantry and artillery and from the Confederate vantage point; the Rebels could not discern where the Federal left actually ended.

The Confederates had a “report…that the enemy had but two regiments of infantry and one battery at the Peach Orchard.” That was far from the case.

Longstreet improvised and swung his second division farther south in hopes of locating the enemy flank, and enveloping it as Robert E. Lee had ordered.

John Bell Hood was a thirty two year old bachelor, who had the perpetual look of sadness across his face. He was described as being as “…ambitious as he was brave and daring…” A graduate of the West Point class of 1853, Hood had distinguished himself in the old army, one of his mentors being Robert E. Lee.

After throwing his hat in with the Confederacy, Hood rose to the rank of brigadier general and led the famed Texas Brigade at Gaines’ Mill and a division at Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. He and his men had reputations as some of the hardest fighters in Lee’s army.

As the plan unraveled on July 2nd, Longstreet shifted Hood’s 7,000 man division south down Warfield Ridge and tied in Hood’s left with the right flank of McLaws.

After arriving in the new position, Hood ordered a half dozen of his trusted Texas scouts to the front. This area of the battlefield had not been scouted since 6 A. M. In the ten hours since Capt. Samuel Johnston had “scouted” the area the tactical situation had completely changed.

Sickles forward movement did not just impact the Emmitsburg Road, it impacted the entire south end of the field. When the Federal 3rd Corps moved forward, Yankee’s pushed west and south, taking up a new, nearly 1½ mile line. While the line took the shape of a large V, with the base of the V resting at the Peach Orchard, where the left end of this V ended was anybody’s guess. Hood’s scouts in front were on the prowl for that flank.

Longstreet became increasingly vexed by the situation. One veteran observing “Old Pete” thought that “his mind had been disturbed, and had more the look of gloom than I had noticed before.”

“The reconnaissance of my Texas scouts and the development of the Federal lines were effected in a very short space of time…” recounted Hood in the postwar years. The scouts told Hood much of what he could see through field glasses. “They [the scouts] soon reported to me that it [the Federal left] rested upon Round Top mountain…the country was open and that I could march through an open woodland pasture around Round Top and assault the enemy in flank and rear; that their wagon trains were parked in rear of their line, and were badly exposed to our attack in that direction.”

Being that Hood recounted all of this in the post war years, it is unlikely that the scouts reported that Little Round Top was held by the Federals, since there was no infantry or artillery atop the hill as of yet. They possibly saw the signal station or a small knot of officers, but the Federal left actually ended in the Plum Run Valley 800 yards from the summit of the hill.

The Federals were in possession of ten acre grouping of rocks called Devil’s Den, which contained four cannon and at least three regiments of infantry. Woods obscured some of the Federal positions, as did hill tops and ridge-lines.

Just like McLaws, Hood did not like his prospects of attacking. In Hood’s words:

“I found that in making the attack according to orders, viz: up the Emmettsburg [sic] road, I should have first to encounter and drive off this advanced line of battle; secondly, at the base and along the slope of the mountain, to confront immense boulders of stone, so massed together as to form narrow openings, which would break our ranks and cause the men to scatter whilst climbing up the rocky precipice. I found, moreover, that my division would be exposed to heavy fire from the main line of the enemy, in position on the crest of the high range, of which Round Top was the extreme left, and, by reason of the concavity of the enemy’s main line, that we would be subject to a destructive fire in flank and rear, as well as in front; and deemed it almost an impossibility to clamber along the boulders up this steep and rugged mountain, and, under this number of cross-fires, put the enemy to flight. I knew that if the feat was accomplished it must be a most fearful sacrifice of as brave and gallant soldiers as ever engaged in battle.”

Hood protested to Longstreet at least three, possibly four times, to no avail. He begged to be allowed to march farther to the east, in hopes of getting in behind Little Round Top (ironically his initial attack path would not carry him atop the heights, but rather the valley below. That all changed when the battle opened). “Gen’l Lee’s orders are to attack up the Emmettsburg [sic] road.” was Longstreet’s response, “We must obey the orders of General Lee.” With that Hood had done all he could to change Longstreet’s mind, to no avail.

The Kentuckian rode to the center of the Texas brigade line and ordered the first of Longstreet’s brigades forward. The Rebels would attack a few brigades at a time. The idea was to draw in the Federals by using an echelon style attack. By releasing only a few brigades at a time, the enemy would send troops to the threatened point and focus there, which, in theory, should weaken or create a hole in the enemy line that the Confederates could exploit.

The Kentuckian rode to the center of the Texas brigade line and ordered the first of Longstreet’s brigades forward. The Rebels would attack a few brigades at a time. The idea was to draw in the Federals by using an echelon style attack. By releasing only a few brigades at a time, the enemy would send troops to the threatened point and focus there, which, in theory, should weaken or create a hole in the enemy line that the Confederates could exploit.

Brigadier General Jerome Robertson walked to the center of his brigade line and shouted “My brave Texans, forward and take those heights!” With that, the second day’s battle opened in earnest.

Today visitors can visit the area from which Hood viewed the Federal line, it is tour stop 7 on the Gettysburg National Military Park driving tour, Warfield Ridge. Yet few actually venture out to the area in which Hood proposed to attack, the backside of Little Round Top.

To fully understand the Little Round Top sector, students of the battle should visit Howe Avenue, just off of the Taneytown Road. From here there is a great view of the backside of Little Round Top. It will also give you an excellent vantage point of what the battlefield would have looked like should John Bell Hood got his wish.

Visitors will notice the open ground of the area, which would have played well into the Federal hands. Shifting Hood’s division to this point would have necessitated the shifting of McLaws division as well, if not the entire Army of Northern Virginia. In theory Longstreet could have been detached from the army a la Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville, with one major difference (beside the fact Jackson had been dead for nearly two months), the Federal’s in this area were receiving major reinforcements from both the 5th and 6th Corps. More from the 12th Corps were also being shifted to the sector too. The bulk of those troops were being funneled onto the field via the Taneytown Road, and entering the field between the northern tip of Little Round Top, one-half mile north of Howe Avenue, and Munshower Knoll.

The 6th Corps was the largest in the Army of the Potomac, numbering nearly 17,000 officers and men. The corps also boasted the largest compliment of artillery of any Federal corps on the field, some eight batteries containing 48 cannon, and 1,007 artillerymen. The best that Hood could bring to the fight were 7,000 infantry and approximately 19 cannon. You can argue one way or the other, but in an open field fight, with these types of numbers, my money is on the 6th Corps-with more Federal reinforcements on hand.

Now let’s consider if Little Round Top had fallen into Confederate hands. Those 48 cannon, bolstered by the Army of the Potomac’s Artillery Reserve, set up on this open ground, would have made staying atop the hill nearly impossible. Not to mention the fact that Hood’s assault was diluted with men fighting in the Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, and Little Round Top Sectors. Some 2,000 worn out Southern infantrymen, with no hopes of reinforcements stood little chance of hold said hill for long. Beside the fact that it would take a superhuman effort to move Confederate cannon across the rock strewn Bushman and Slyder farms to reach Little Round Top and support said infantry.

The next time you debate the fight for Little Round Top, I urge you to stop by Howe Avenue and take in the vista, it may just change your perception of the battle.

Authors Note:

Howe Avenue is named for Brig. Gen. Albion P. Howe. Howe commanded the 2nd Division of 6th Corps. While the avenue is named in his honor, most of the monuments along the road are to troops of Horatio Wright’s division of 6th Corps, and were some of the same troops that captured Marye’s Heights two months prior.

To Reach Howe Ave:

From the town square, follow Baltimore Street south for 0.5 miles.

At the Y intersection bear to the right and follow Steinwehr Ave. for 0.2 miles.

At the traffic light, turn left onto the Taneytown Road.

Follow the Taneytown Road for 2.6 miles and then turn left onto Howe Ave. (If you cross over the top of the 15 bypass you have gone too far.

To Reach Warfield Ridge:

-From the town square, follow Baltimore Street south for 0.5 miles.

-At the Y intersection bear to the right and follow Steinwehr Ave. (which turns into the Emmitsburg Road), for 2.6 miles.

-Turn left onto South Confederate Ave. Follow the avenue for 0.2 miles. Tour Stop 7 will be on the left and side.

Greta post, with one small caveat — although Hood protested a direct assault on Little Round Top, he didn’t do so in person, as depicted in the 1993 film Gettysburg. It was all done through aides and couriers.

The movie version plays better, though.

Andy,

Agreed. It does play out much better in the movie. For simplicity sake of the article I left out the running back and forth of the aides. I personally don’t think it would have made a difference if they had met in person. Longstreet’s mind was made up that he was going to attack come hell or high water, almost felt like he was doing it to spite Lee. Regardless, he and his men put up one hell of a fight for the south end of that field.

Indeed. I had a relative in the Fourth Texas Infantry who went through that. Near the end of his life he dictated his wartime experiences at Second Manassas, Sharpsburg, and Chickamauga — but not Gettysburg. I never have found out why, unless they were too much for him to relive.

i have gone out to this site and can attest it will change your mind about the round tops . try it . thank you for a eye opener.

Hi Guys. I live in the UK, My great, great, great uncle Capt. John Cussons, who originated from Lincolnshire, was Gen. Law’s ADC and commander of Law’s Brigade’s scouts and sharpshooters. I’ve been doing a lot of research on him and the 2nd and 3rd days at Gettysburg, where he was captured, and visited the battlefield last spring. I agree with Thomas Place Sr. that the site is an eye opener. However, to imagine that there were far more trees back in 1863 and what the troops of Hood’s division had to endure even before the fight started is something to really take into account too.

Andy, I see your ancestor was at Sharpsburg but not Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville or Gettysburg? Perhaps he was wounded or caught Typhoid fever? There were quite a few instances of the Typhoid in both armies at that time. Great post by the way!

How tactically important was the both of the Round Tops. “Attack up Emmitsburg rd” turned into an assault on the Round Tops trying to turn the flank of the Union Army….although the actual flank was at Devil Den at the start of the attack. The time Hood spent trying to convince Longstreet to let him go around Big Round Top probably took 30/45 min. Vincent’s Union Brigade reached Little Round Top just 10 minutes before Hood’s division reached Little Round Top.

If, instead of the men used in making the assault on the Round Tops, had been been used in attacking Ward’s Brigade at Devils Den and the Triangle field, would that not have led to a quicker riot Ward’s brigade and the whole division of Hood’s men getting to the key position of the Wheat field rd before Caldwell’s Union Division could counterattack.

The lost time, not to even mention the counter march, beginning from the time McLaws sees Sickles in the Peach Orchard to the time Hood attacks, is a period of two hours. This was two hours of arguing and maneuvering over what action to take with the Confederate forces. Ultimately, McLaws did attack the Peach Orchard at 6pm which was then probably more defended with cannon than at 3pm.

If everyone had done just as Lee had said and attacked “up Emmitsburg rd” at 3:30/4:00, I believe Hood’s division coming in behind McLaws would have reached the area around the Pennsylvania Memorial before 6th Corp arrived and the Union Army would have been forced to look for a more suitable defensive position.

The Confederate attack, as planned by Longstreet, with Hood going first even works if Hood doesn’t send men to the Round tops and they are used up Plum Run, they would have reached the Wheat Field rd before Vincent’s Brigade could reach Little Round top. A 30/45 minute earlier attack puts Vincent’s brigade at Wheat field rd and no one on Little Round Top. I put the failure of the July 2nd attack on Hood for first being argumentative about the orders given him which delayed the attack and then sending men up the Round Tops which held no tactical value, was undefended, and was not in his orders to do so.

This view is from the information I have been able to ascertain, but I would eagerly like to learn more about the time lapse between when McLaws sees Sickle’s in the Peach Orchard to when Hood’s division attacks. I’ve heard that everyone was stumped about what to do and even that Lee was there and then the orders were changed to have Hood’s Division start the attack instead of McLaws. My thoughts are that the 2nd days battle was lost in that 2 hour delay between 3pm and 5 pm and I would love to learn everything I could about that time and what was taking place on the Confederate side.

I don’t think it was a 2 hour delay from when McLaws went into position on Seminary Ridge to Hood’s attack.