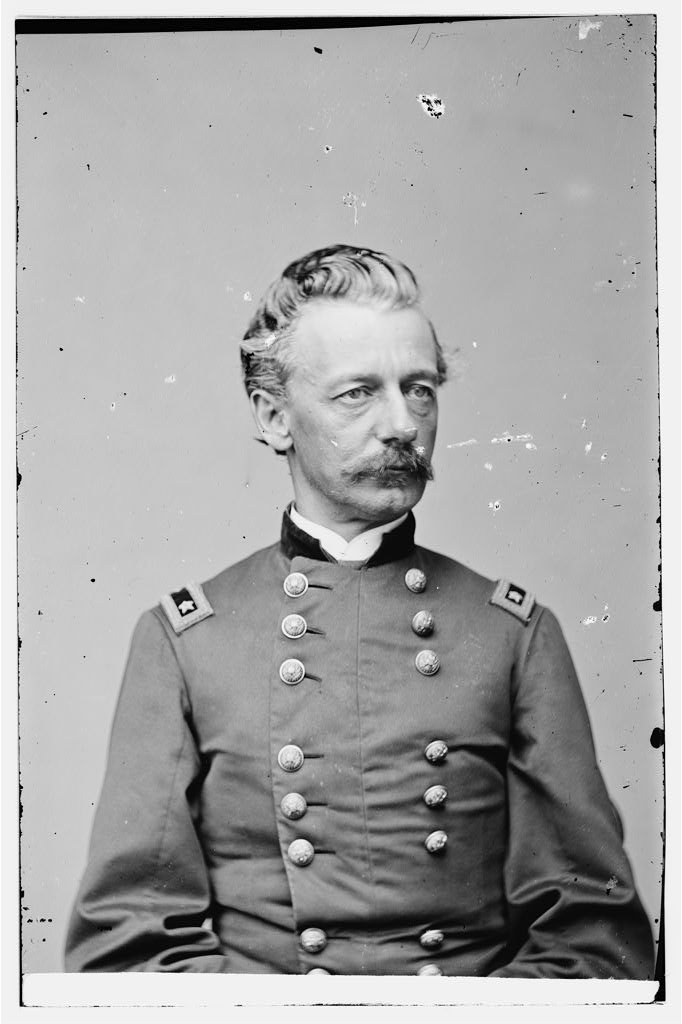

Showing the White Feather”: The Civil War Ordeal of Col. William H. Christian

We are happy to welcome guest author Kristen M. Trout. Kristen is a life-long student of the Civil War, and holds a degree in History from Gettysburg College and is currently working towards her MA in Nonprofit Leadership from Webster University in St. Louis, Missouri. A native of Wildwood, Missouri, she has worked in the National Park Service and is currently on staff at the Missouri Civil War Museum in St. Louis. Her focuses of study include Civil War medicine and military history, particularly of the experiences of the average soldier.

For many a soldier, the Battle of Antietam was the great testing of “indomitable courage,” as they were required to endure not only the twelve hours of brutal combat, but sustain the heavy losses of many of their brothers in arms.[1] Although the majority of men on both sides were able to mentally cope and perform their duties under heavy fire and bloodshed, some could not take the stress and broke down by deserting or skedaddling to the rear. One of the most fascinating, yet sad cases of cowardice on the battlefield is that of Col. William Christian, commander of the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division of the First Army Corps at Antietam.

By 1861, the Utica, New York native was drillmaster of his hometown’s volunteer militia unit and was the city’s chief surveyor. At the age of twenty-one, he put in two years of service in the Mexican War with the First New York Volunteers, in which he and his fellow soldiers were a part of the occupation force of the presidio of San Francisco, California. [2] Christian was passionate and patriotic for his country. He displayed the discipline of a trained soldier and clearly had the leadership potential to command a military unit.

Soon after the news of the fall of Fort Sumter, Christian was determined to form his own regiment in service to the State of New York and the United States. In combination with his military experience and determination, he was given permission by Governor Edwin Morgan to form a regiment.[3] By early May, the entire 26th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, representing central and eastern New York, was organized and mustered in for service. According to the Utica Morning Herald and Daily Gazette, Christian was acknowledged on several occasions for, “military skill and energy,” having “the best-drilled volunteer regiment,” and “energy and firmness.”[4] The thought of him being an incompetent or ineffective combat commander would never have crossed their minds at this point in the war.

The first signs of Christian’s inability to command and control his apparent battle phobia appeared early on in the war. After protecting the rear of the defeated Army of Northeastern Virginia in July 1861, Christian was selected by brigade commander Brig. Gen. Henry Slocum to lead a 300-man detachment on an expedition to Pohick Church, Virginia to capture a small detachment of Confederate cavalry on October 4. Due to inexperience and an inability to command, Christian’s expedition was a disaster. He and his men failed to not only execute the tactics; they failed to capture any troops. Even worse, Christian could not control his men during their return, as they plundered the Virginia countryside and even killed one of their own. To Slocum, Christian’s men violated one of McClellan’s orders to not use excessive force against Southern civilians. To clear his name, Christian demanded a court of inquiry. . Although the court of inquiry never occurred, Christian’s regiment was immediately transferred from Slocum’s brigade and assigned to Fort Lyon in Washington until May 1862.[5]

Did Col. Christian lose command of his men due to their lack of respect for him? Or did he lack the resolve to carry out his orders, fearful of combat? The answer may never be known, but Christian’s actions at Second Manassas in August 1862 may reveal a hint as to what might have happened at Pohick Church.

By the time the armies of Virginia and Northern Virginia collided near Manassas Junction along the Warrenton Turnpike in late August, Christian had already displayed bouts of combat fatigue and anxiety in the face of artillery fire at the Rappahannock River just a week prior.[6] Now, he was expected to lead his men into heavy combat for the first time. As his regiment was about to go into battle on the 30th, Christian became suddenly ill with what the physician Dr. Coventry thought was sunstroke.

Although the weather was quite hot and dry that morning and the previous days, sunstroke could not have been the cause. According to The Johns Hopkins University, headaches, dizziness, disorientation, dry mouth and tongue, and hallucinations are all symptoms for heat stroke.[7] He was exhibiting symptoms of dizziness and disorientation, but Christian’s subordinates recalled that he was feeling fine just before and he was himself immediately after the battle. Victims of heatstroke typically take weeks to fully recover due to the extreme toll on the body.

What is more probable is that the colonel was having a panic attack caused by either a fear of going into battle or even having a form of post-traumatic stress disorder from previous combat experiences. Lasting for minutes, panic attacks can make a victim “have a strong physical reaction […] it may feel like having a heart attack.” In addition, panic attacks can lead to “pounding or racing heart, sweating, breathing problems, weakness or dizziness, feeling hot or a cold chill, tingly or numb hands, chest pain, or stomach pain.”[8] As the regiment marched into battle, Christian was laying under a tree with a blanket and water.[9]

His fellow officers and men were not pleased by Christian’s absence that day, especially since the unit lost 169 men, making it one of the heaviest losses for a regiment at Manassas.[10] When he did arrive back at camp that evening, Christian tried to regain his honor and dignity amongst the men. Even with his persistence, many of the troops were suspicious of his behavior. Was he a coward? After all, to Civil War armies, courage lay at the heart of their ability to fight. When a unit commander is unable to have courage, how can they lead? Once they discovered Christian was to assume command of the 2nd Brigade after the wounding of Brig. Gen. Zealous Tower, some of the men from his regiment were willing to petition for his removal from command. It never went through.

By the next month, the Army of the Potomac was on the move north in pursuit of the invading Army of Northern Virginia. At the battles of Chantilly and South Mountain, Christian’s 2nd Brigade performed well in the light combat they experienced. Their fortune was limited however as they made their way west to Antietam Creek.

The morning of September 17, the brigade, along with the rest of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s First Army Corps, crossed the north bridge over the Antietam. Aligned on the extreme left of the corps’ battle line, Christian’s brigade advanced south from the Poffenberger Farm through the East Woods, parallel to the Smoketown Road. Quickly, the brigade was swept up in combat against Isaac Trimble’s Georgians, North Carolinians, and Alabamians. Heavy Confederate artillery fire from Nicodemus Heights to the west and Col. S.D. Lee’s guns from the south battered the brigade as they made their way south over the open ground.

With all the crossfire from Rebel artillery, Col. Christian started faltering again. He shuttered at every explosion, but knew he could not just run to the rear. The colonel was in command now of an entire brigade engaged in heavy combat. He had no fallback this time. As seen just months prior to Antietam, Christian’s men made note that he was losing his cool in the face of artillery fire along the Rappahannock. Additionally, before deploying at Second Manassas, heavy artillery fire surrounded the regiment. He was cool under musket fire at Chantilly and South Mountain, but was the excessive artillery fire the cause of his panicking?

Under heavy stress, Christian shouted marching orders he was so familiar with from the days of drill mastering the Utica militia and training the 26th New York. Going back to the routine of drill and marching was not an uncommon site amongst Civil War volunteer units. It relaxed these soldiers and made the processes of marching, loading, and firing smoother and more comfortable. But for the colonel, his orders to “forward march!” and “guide center!” were incessant. In addition to shouting orders to stay calm, one of his men in the 26th New York recalled, “he [Christian] would duck and dodge his head and go crouching along.”[11]

The continuous artillery fire upon the advancing Federals and the lines of Confederate infantry in front of them caused Christian to lose his cool. In a postwar document by a soldier in the 90th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Christian even said, “he had a “great horror of these shells.””[12] Unable to control himself any longer, he dismounted from his steed and skedaddled to the rear whilst screaming that they had lost the battle.[13] He nearly caused a mass panic amongst the troops of the First Corps and abandoned his brigade on the field. Col. Peter Lyle of the 90th Pennsylvania assumed command of the 2nd Brigade after word got back to division commander Brig. Gen. James Ricketts.

Soon after his episode, Christian was spotted shaking under a tree behind the lines by Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour. That evening, Ricketts called Christian into his tent to discuss the pressing matter. He demanded the shell-shocked commander’s resignation immediately, or else be court-martialed. The next day, Christian’s resignation was submitted to Ricketts, and Lyle was promoted to brigade commander.

Even though Christian had resigned that day after Antietam, nothing was ever said of his actions beyond minor correspondence in the postwar era. After-action reports and other correspondences written by Ricketts, Lyle, and other commanders who served with Christian at Antietam never made any mention of his episode. Additionally, nothing further was said about him to the Utica community beyond his sudden, mysterious resignation. Christian was ultimately granted an honorable discharge from Ricketts and was seen by his men and community in Utica, New York as, “a man of many noble qualities […]”[14] His commanders were so fond of his character they promoted him to brigadier general, even after Antietam. Even the men he failed continuously invited their poor leader to regimental reunions. To speak further of Christian’s character, his men rallied behind his wife when she requested pension after his death. His qualities ultimately outweighed his weaknesses. After all, his only downfall as a leader was not being able to overcome his fear of shellfire.

Throughout the remainder of his rather short life, sadly, Christian suffered from severe depression as a result of his failed military career. His mental state was so poor that he became unable to work in civil engineering any longer. As the years went by, the former officer lost control of his mind, laughing hysterically at random times and pretending he was back on the saddle of his horse leading the 26th New York. In 1886, his wife, unable to care for her fading husband, admitted him to the Utica Insane Asylum. In one year, Christian supposedly passed away from dementia, even though his friends and family argued it was sunstroke from Second Manassas. The broken soldier was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica, lying beneath his headstone adorned with his military service, and the war eagle and American flag.[15]

Endnotes:

[1] Robert E. Lee, General Orders No. 116, October 2, 1862, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, ser. 1, vol. 19, part ii, 643-644.

[2] Francis D. Clark, The First Regiment of New York Volunteers, Commanded by Col. Jonathan D Stevenson in the Mexican War (New York: Geo. S. Evans & Co. Printers, 1882), 47-48; http://www.archive.org/stream/firstregimentofn00clarrich#page/46/mode/2up.

[3] Paul Taylor, Glory Was Not Their Companion: The Twenty-Sixth New York Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2005), 6.

[4] “A Compliment,” Utica Morning Herald and Daily Gazette, August 1, 1861, New York State Military Museum (hereafter cited as NYSMM); Letter from Aliquis to the Editor of the Utica Morning Herald, August 4, 1861, in Utica Morning Herald and Daily Gazette, NYSMM; Letter from Aliquis to the Editor of the Utica Morning Herald, June 2, 1861, in Utica Morning Herald and Daily Gazette, NYSMM.

[5] Brian C. Melton, Sherman’s Forgotten General: Henry W. Slocum (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 63; Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 33-35.

[6] Pvt. Charles McClenthen Diary, Manassas National Battlefield Park Library, 7 in Taylor, Glory Was Not Their Companion, 57; It is important to note that although his men thought he behaved oddly in battle, Christian’s commanding officers and newspapers report he “behaved with great gallantry,” from The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, August 25, 1862.

[7] “Dehydration and Heat Stroke,” Johns Hopkins Medicine, http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/non-traumatic_emergencies/ dehydration_and_heat_stroke_85,P00828/.

[8] “Panic Disorder,” National Institute of Mental Health, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/panic-disorder/index.shtml.

[9] John Hoptak, “Poor Bill Christian…” November 5, 2007, The 48th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry Blog, http://48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com/2007/11/poor-bill-christian.html.

[10] William Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (Dayton, OH: Morningside Bookshop, 1985), 431.

[11] Account of the Battle of Antietam, W.H. Holstead, 26th New York Volunteer Infantry in Tom Clemens, “Col. William Christian,” The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, http://marylandcampaign.com/2011/05/col-william-a-christian/.

[12] Letter from George W. Watson to John M. Gould, April 22, 1893, in Christian’s Brigade Folder, First Corps Box, Carman Letters, Antietam National Battlefield Library, Sharpsburg, MD.

[13] Taylor, Glory Was Not Their Companion, 80.

[14] Letter from William H. Holstead to John M. Gould, in Christian’s Brigade Folder, First Corps Box, Carman Letters, Antietam National Battlefield Library, Sharpsburg, MD.

[15] Hoptak, “Poor Bill Christian…”

What a great piece of writing! So glad so much attention to leadership qualities, character, and mental status. I found myself trying to imagine being with him and his men in combat. Leadership can be lonely. I would have done better as a pvt being able to touch my compadres elbows for moral and mental support. What terrible situations. Thank you again for letting me be with these men during these hellacious times.

This is an excellent article! Lesley J. Gordon is one historian leading the efforts to examine instances such as these. Her book A Broken Regiment: the 16th Connecticut’s Civil War is an excellent read. So often we come upon sentences such as, “He was an excellent brigade commander, but his promotion was a disaster.” In my own studies of the 11th New York (Ellsworth’s Fire Zouaves), I have come to realize just how important good leadership is at all levels of command. Without a solid command structure, unit cohesion is sketchy at best. No soldier wanted to think his efforts were a waste of time and effort. It took, and still takes, good officers to direct the soldiers. Without this, you end up with the Fire Zouaves running around the battle field trying to “help” by falling in with other units or, even worse, fighting singly.

Col. Christian was, I think, harder on himself than history has been.

thank you for a great 1st person article really liked the way it was written as i easily followed along in my west point civil war atlas be looking for more .

I live in the house that William H Christian sold to last name ocsar