“Not written in letters of blood.”

Edwin M. Stanton to Major General William S. Rosecrans, July 7, 1863:

“We have just received official information that Vicksburg surrendered to General Grant on the 4th of July. Lee’s army overthrown; Grant victorious. You and your noble army now have the chance to give the finishing blow to the rebellion. Will you neglect the chance?”

Upon reading this dispatch in his newly established headquarters at Tullahoma Tennessee, Rosecrans must have been stunned. Certainly he was angered.

The Army of the Cumberland had just concluded its own arduous operation; an extended turning movement aimed at outflanking Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee from a line of hills south of Nashville, where Bragg’s men had been since the retreat from Stones River, 6 months before. This movement did not result in a climactic battle, like the one in Pennsylvania; nor did it result in the capture of an entire Rebel Army, like Vicksburg.

Stanton’s subtext was clear: ‘what have you done for me lately?’

On the heels of Rosecrans’s victory at Stones River, administration gratitude flowed down the telegraph wires in virtual torrents. Over the spring and summer, that tone changed. Carping and complaint ruled the day. Lincoln and Stanton needed action; Rosecrans preferred meticulous preparation.

Unquestionably, Rosecrans erred on the side of caution that spring. In early June, when Bragg’s army was being depleted in order to reinforce the Rebels confronting Grant in Mississippi, Rosecrans first denied those troop movements were occurring, and then suggested that it would be better for his army to wait and see the outcome of Grant’s campaign; if his army should be defeated, then only Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland would be left to redress the balance.

This was flawed strategy; a poorly thought-out argument coming from a man who usually had a firm grasp of military affairs.

Which is why Rosecrans commenced his long-awaited – and long prepared-for – advance barely three weeks later, on June 24.

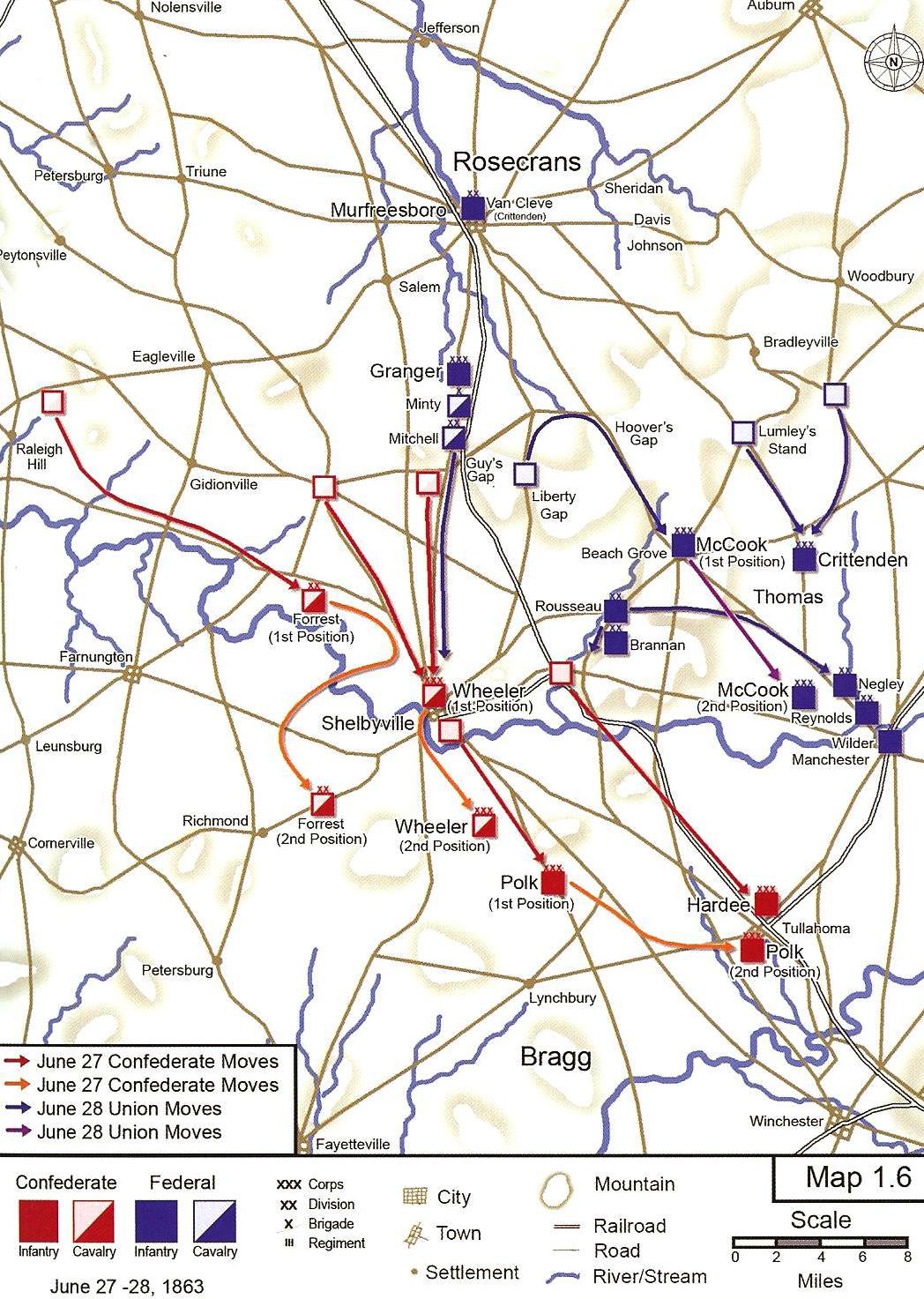

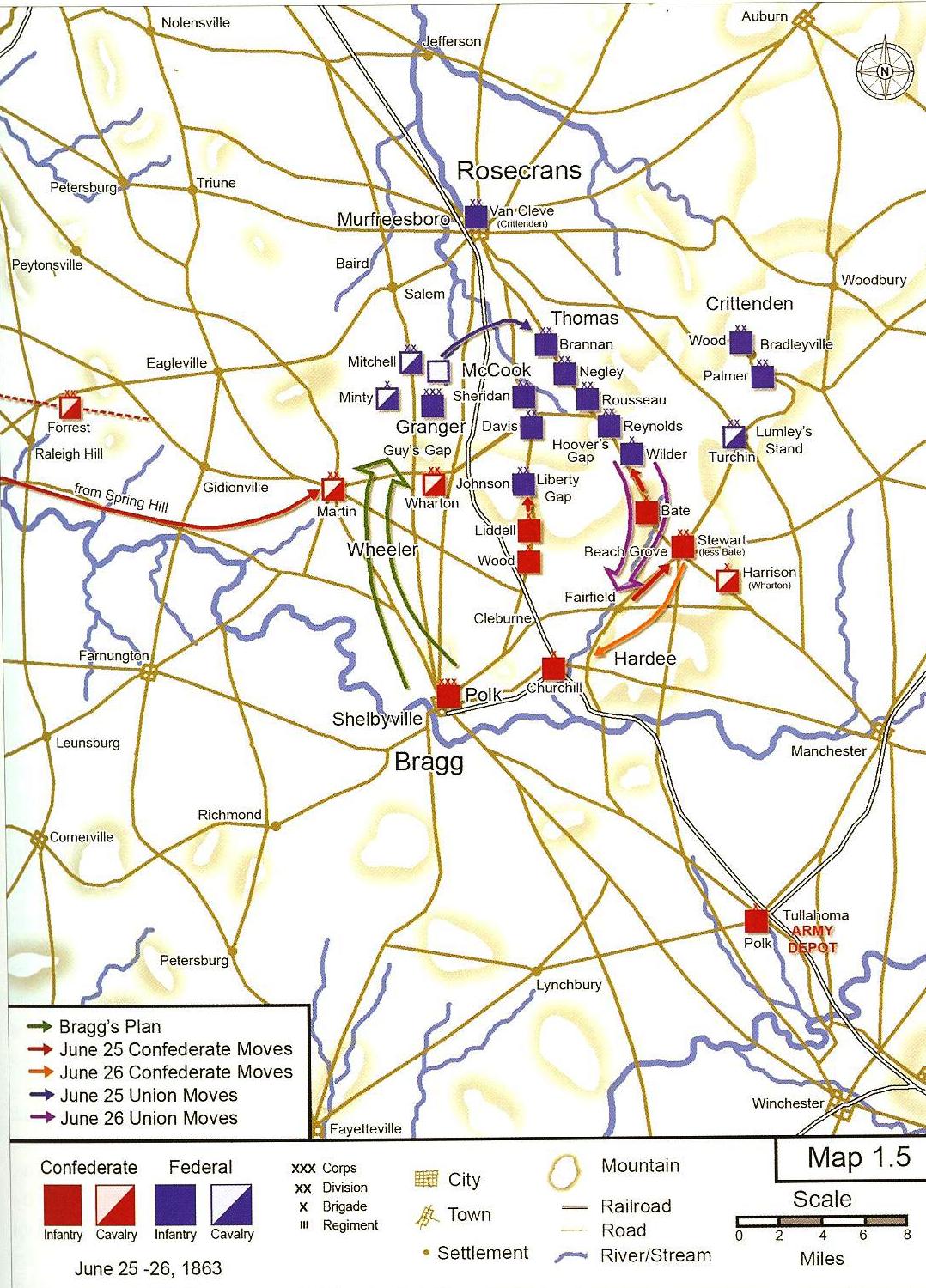

Bragg’s army was stretched across a front of about 30 miles, with cavalry on each flank; his infantry deployed at Shelbyville, Wartrace and the hamlet of Beech Grove. Bragg’s supply depot lay at Tullahoma. Guy’s Gap, Liberty Gap, and Hoover’s Gap lay between Rosecrans and his opponent; narrow defiles which, if stoutly defended, offered Rosecrans only the prospect of bloody frontal assaults.

So Rosecrans opted for a different approach. By feinting against the gaps while flanking Bragg to the east, Rosecrans intended to march a corps unopposed first into Manchester and then on to Tullahoma. Capturing that place would not only cripple Bragg’s logistics, but it would also potentially cut Bragg’s best retreat route.

The strategy worked. By June 27, The Union XXI Corps entered Manchester. But strategy, no matter how carefully planned, could not overcome the vagaries of weather. Drenching rains slowed both armies movements, but with Bragg moving on the chord while Rosecrans maneuvered on the rim of the circle, Bragg escaped the trap. Bragg retreated to Tullahoma before Rosecrans could seize the place. Subsequently, Bragg retreated out of Middle Tennessee entirely, falling back to Chattanooga rather than risk battle.

The strategy worked. By June 27, The Union XXI Corps entered Manchester. But strategy, no matter how carefully planned, could not overcome the vagaries of weather. Drenching rains slowed both armies movements, but with Bragg moving on the chord while Rosecrans maneuvered on the rim of the circle, Bragg escaped the trap. Bragg retreated to Tullahoma before Rosecrans could seize the place. Subsequently, Bragg retreated out of Middle Tennessee entirely, falling back to Chattanooga rather than risk battle.

Rosecrans was elated. Yes, Bragg had escaped, but some of the most difficult terrain ahead was now in Union hands with barely a shot fired, and Rosecrans could embark on the planning for his next objective, Chattanooga. Losses were light. Rosecrans suffered a total of 570 casualties. Confederate losses were never fully articulated, but the Yankees reported the capture of 1600 prisoners, with at least 300 known combat losses.

Perhaps the fullest extent of the damage done to Bragg’s army can be found in his June 20 and July 10 returns. On June 20th, Bragg reported 50,407 officers and men present for duty; and an aggregate present of 59,527. 20 days later, in Chattanooga, those numbers shrank to 44, 250 for duty, or 52,122 aggregate. In three weeks, between six and seven thousand men disappeared from the ranks. Some were killed or wounded, but most deserted.

It is not surprising, then, that Rosecrans felt slighted when he read Stanton’s telegram, and the implied rebuke. His reply speaks volumes.

“You do not appear to observe the fact that this noble army has driven the rebels from Middle Tennessee, of which my dispatches advised you. I beg on behalf of this army that the War Department may not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood.”

Excellent tribute to a completely forgotten Union victory. Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Atlanta, and beyond would have been impossible without Tullahoma.

This fine article hints at the military politics that poisoned the Union war effort.