The Underground Railroad Offers a Harrowing Journey through American Race Relations

As a boy, Colson Whitehead imagined an underground railroad full of steam engines that ran through tunnels deep beneath the Antebellum earth on routes that stretch to indeterminate places. He was disappointed to discover the railroad—as important as it was in helping escaped slave reach freedom—was only a metaphor.

As a boy, Colson Whitehead imagined an underground railroad full of steam engines that ran through tunnels deep beneath the Antebellum earth on routes that stretch to indeterminate places. He was disappointed to discover the railroad—as important as it was in helping escaped slave reach freedom—was only a metaphor.

In his unflinching new novel, The Underground Railroad, Whitehead makes the metaphor literal—and literary.

The novel focuses on Cora, a young slave toiling on a Georgia plantation owned by the Randall family. When the patriarch of the family dies, his household slaves are invited to serve as pallbearers—a position of honor that reflects his former esteem for them. His sons take over the plantation: James, with “a nautilus disposition, burrowing into his private appetites,” and Terrance, who “inflicted every fleeting and deep-seated fancy on all in his power.”

When James dies under scandalous circumstances in a New Orleans house of ill repute, Terrance takes full control. As a practitioner of public torture porn—which Whitehead depicts with the matter-of-factness of a planter reviewing his account books—Terrance exercises a monstrous reign.

Cora, surprised to discover that the rumored Underground Railroad actually has a spur so deep into Georgia, decides to make a break for it. She kills a young slave catcher during her escape, though, so the hunt for her doubles-down.

Cora’s flight echoes the “hero’s journey” epics of classic literature, but along the way, her journey subtly shifts from reality to metaphor to allegory. She descends beneath homes and barns and into caves to find train stations of all sorts, from those of unexpected ornateness to others of disheartening abandonment.

The cars that transport her on her flight vary from “one single car, a dilapidated boxcar missing numerous planks in its walls” to “a proper passenger car—well appointed and comfortable like the ones she’d read about . . . . There were seats enough for thirty, lavish and soft, and brass fixtures gleamed where the candlelight fell.”

“To call the flatcar a coach was an abuse of the word. . .” the protagonist, Cora, discovers elsewhere. “The plane of wooden planks was riveted to the undercarriage without walls or ceiling.” She even finds, in a forgotten ghost tunnel, “a small handcar . . . its iron pump waiting for a human touch to animate it.”

Cora’s journey becomes akin to a trip through America’s trouble history of race relations, out of slavery and into the fire. “Every state is different,” one character says—an observation that’s as much warning as fact. Every state serves as an archetype, yet Whitehead based each scenario on specific historic events, too.

The result: each state also becomes an allegorical landscape unto itself.

South Carolina’s seemingly enlightened coexistence between whites and blacks covers up a Tuskegee-like initiative where blacks are the subjects of medical experimentation without their knowledge.

North Carolina embraces militant white supremacy to such an extent that being black is a capital offense. Settlements have “Freedom Trails”—lynching-lined byways in and out of town where “corpses hung from trees as rotting ornaments.”

Tennessee, meanwhile, “proceeded in a series of blights,” a series of disasters that “were the fruit of indifferent nature, without connection to the crimes” of anyone, Whitehead writes. “If Tennessee had a temperament, it took after the dark personality of the world, with a taste for arbitrary punishment.”

Even Ohio, where Cora settles in a Utopian community of all-blacks, parallels the troubles African-Americans had in their northern migration to the cities in the early part of the twentieth century. Tensions between leaders in the community—akin to the differing philosophies of W. E. B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington or, later, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X—serve to undermine stability and advancement.

The novel ends with Cora’s journey still ongoing. The road out of bondage remains befuddling, with no end in sight, although Whitehead suggests a resigned, weary movement that might be progress. He leaves it to the reader to consider these things, just as Cora does—with the next leg of the journey stretching ahead, waiting.

————

National Public Radio’s program Fresh Air interviewed Whitehead about his book on August 6, 2016. You can listen to the interview here.

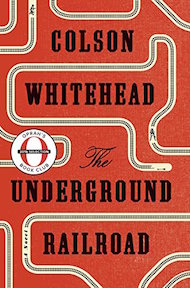

The Underground Railroad was selected for the Oprah Book Club: “Every now and then a book comes along that reaches the marrow of your bones, settles in, and stays forever. This is one. It’s a tour de force, and I don’t say that lightly.”— Oprah Winfrey

Read more: http://www.oprah.com/book/the-underground-railroad-colson-whitehead#ixzz4MEIF1ZLW

Reblogged this on Practically Historical.

This sounds like a really neat book; however, books like this (and culture at large because of its emphasis on the Underground Railroad) concern me because the myth of the Underground Railroad does much to undermine the true nature of enslavement. At best 1-3% of enslavement peoples went “on” this railroad. Historical memory relies to much on narratives that tend to make the past better than it was.