1860 Politics – Lincoln-Douglas Debates Continue: Moral Consensus and Thin Democracy

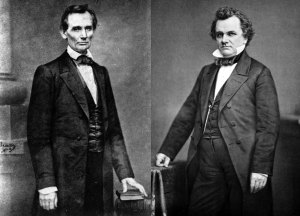

The Lincoln-Douglas debates for the U.S. Senate seat from Illinois were in many ways unlike presidential debates we see on television today, but fundamental themes underlying them demonstrate historical continuity.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates for the U.S. Senate seat from Illinois were in many ways unlike presidential debates we see on television today, but fundamental themes underlying them demonstrate historical continuity.

One of those themes is consensus concerning foundational moral principles, a cornerstone of a healthy polity. Citizens of a republic must clarify right from wrong by electing representatives who will pass and enforce laws reflecting such a consensus. When accord breaks down, the society is in trouble.

On October 13, 1858, Abraham Lincoln spoke to the crowd at Quincy, Illinois about the most divisive controversy of the time. It was a disturbing issue. It was a dangerous issue. They would be better prepared, he noted, to discuss the matter if it was properly defined. Reduced to its lowest terms, it was, “no other than the difference between the men who think slavery a wrong and those who do not think it wrong.” It was Lincoln’s sixth debate with incumbent senator and former judge Stephen A. Douglas.[1]

How could Americans of that era have held such antagonistic views? It is appalling to us now that many citizens then argued so forcefully in favor of such a reprehensible practice. It also can be inexplicable, and therefore tempting to simply dismiss those people as intellectually and morally inferior.

Much has changed in a century and a half. But if one assumes human nature as a constant within a common moral ethos, and if one assumes that the motivations of fellow citizens are explicable—not just the result of collective inferiority—a comparison between then and now as reflected in Lincoln’s words sheds light on both eras.

Only that one issue split the body politic profoundly back then. After effusion of much blood, the question would be resolved with moral and legal clarity, but that was not obvious to the people listening to Lincoln in Quincy. Secondary concerns—states’ rights, tariffs, infrastructure improvements, banking, etc.—caused debate and angst, but they would not of themselves have led to secession and civil strife. Despite differences among regions, on most other social, cultural, and civil topics it could be argued that the nation was more united in 1858 than it is now.

We have no one great problem today, but the people seem increasingly antagonistic about many things, manifesting cracks in the moral consensus. Today’s issues continue to be profoundly disturbing and even dangerous in the minds of many Americans; their parameters are unclear, and although conditions for civil war do not seem apparent, no solutions are in sight. Our problems are more diffuse, but not necessarily lesser in moral weight or importance.

In the contemporary world, proponents of various controversies seem to stand in the same relationship to each other as Lincoln and Douglas did then. If we set aside for the moment the obvious dissimilarities and focus on the basics, perhaps we can, again, learn from Mr. Lincoln. Perhaps also we can develop a better understanding of how future Americans might judge us.

Following his single term in Congress (1846-48), a discouraged Abraham Lincoln exiled himself from politics until, that is, passage of the Kansas-Nebraska bill in May, 1854. The issue, “aroused him as he had never been before,” Lincoln wrote; it, “took us by surprise—astounded us.” Under the primary sponsorship of Senator Douglas, the law repealed the 1820 Missouri Compromise, opening all territories to the possibility of slavery following the theory of “popular sovereignty.” It also brought Lincoln energetically back to the stump, propelled him into the senatorial contest, and finally to the presidency.[2]

His opening campaign speech in Springfield began with popular sovereignty. It had been five years since Douglas promised that this new approach would bring the nation together under a compromise that most could accept, putting an end to “slavery agitation.”

His opening campaign speech in Springfield began with popular sovereignty. It had been five years since Douglas promised that this new approach would bring the nation together under a compromise that most could accept, putting an end to “slavery agitation.”

But that agitation had only grown worse, said Lincoln, and in his opinion, “it will not cease until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure permanently, half slave and half free.”[3]

Lincoln was vilified for these words, but he was not—as the opposition would insist—predicting disunion, advocating force, or inviting conflict. He simply was observing the dynamics of the controversy, what we might call a binary question: the fundamental premises of the two sides were mutually exclusive and incompatible. The house would at some time become all one thing or all the other: “Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the States.” Although this process could take time (perhaps a century he thought in 1858), it was inevitable.[4]

Current controversies tend to exhibit a similar dichotomy in incompatible premises, a seeming lack of middle ground, with a similar prognosis of all one or all the other resolution. Thus, the concept of popular sovereignty offers one basis of comparison with the past. Popular sovereignty maintained that inhabitants of a territory should choose for themselves whether to allow slavery or not during the process of becoming a state. The federal government in any of its branches could not and should not interfere with this will of the people, and citizens of existing states had no say, which policy if properly followed would preclude further controversy of the kind that had been tearing at the nation for half a century, or so it was alleged.

“Douglas, no less than Lincoln, saw in the American experiment the trial of the cause of political freedom for all humanity,” wrote historian Harry Jaffa. Popular sovereignty was to Douglas the foundation of political freedom. Echoing Daniel Webster, he believed that the Revolution had been fought over the concept of absolute rule exemplified in the preamble to the Stamp Act, which asserted the right of Parliament to bind the colonies in all cases whatsoever. The stamp tax itself was inconsequential but the principle was transcendent.[5]

To Douglas, Lincoln’s insistence that Congress might intervene to prevent the spread of slavery in the Western territories gave the federal government a green light to legislate domestic institutions and to determine the character of future states. He resented Lincoln’s appeal, “to the moral sense of justice, and to the Christian feeling of the community to sustain him.” On that basis, Douglas argued, “Mr. Lincoln…calls on Congress to pass laws controlling their property and domestic concerns without their consent and against their will.” These were choices for the people and only the people living in territories wishing to become states. Douglas was arguing for their right to create a state constitution for themselves as best suits themselves.[6]

For Lincoln, popular sovereignty was, “the most arrant humbug that has ever been attempted on an intelligent community…. I suppose that Judge Douglas will claim in a little while that he is the inventor of the idea that the people should govern themselves; that nobody ever thought of such a thing until he brought it forward.” And the notion that Lincoln was arguing against the people’s right to create their own state constitution was quixotic: “I defy contradiction when I declare that the Judge can find no one to oppose him on that proposition.”[7]

The notable argument of popular sovereignty, Lincoln continued, was otherwise called the sacred right of self-government. This latter phrase, “though expressive of the only rightful basis of any government, was so perverted in this attempted use of it as to amount to just this: That if any one man chooses to enslave another, no third man shall be allowed to object.” His point: Was self-government, including the right to create a suitable state constitution, unqualified? Did it include a right to choose to enslave others?[8]

Jaffa noted that the Lincoln-Douglas debates were concerned in the main with one great practical and one great theoretical question. The practical question was whether federal authority may and should be employed to limit the expansion of slavery into the territories. “The theoretical question was whether slavery was or was not inconsistent with the nature of republican government; that is, whether it was or was not destructive of their own rights for any people to vote in favor of establishing slavery as one of their domestic institutions.”[9]

If we generalize those questions and apply them to any number of today’s issues, the practical question becomes: How and to what degree should government authority, federal or state, be employed to restrict choices of individual citizens? The theoretical question: Are “rights” claimed by particular groups consistent or inconsistent with the nature of republican government; is it or is it not destructive of their own rights for any people to demand legal sanction–with prosecutorial punishment–for causes that many (and perhaps a majority) consider inimical to foundational moral principles? Indeed, what is the moral consensus and do our representatives and judiciary accurately reflect it? We know Abraham Lincoln’s answers to the slavery questions. He might guide us in looking at other issues for the same reasons.

Political philosopher Michael Sandel saw the debates as a prime example of the conflict between responsibility and selfishness. As explained by historian Allen Guelzo: “Douglas, for Sandel, was the paragon of a ‘thin’ notion of democracy, in which a preoccupation with personal rights trumps all notions of advancing a common good, and the citizen degenerates into an ‘unencumbered self’ whose politics is moved—when it is moved at all—by sentimentality. Lincoln, by contrast, saw politics as moved by a universal and shared morality, and opposed slavery as a violation of that morality.[10]

“Douglas argued that the people ought to be allowed to make up their own minds about slavery…and that all that mattered was whether the process of making up those minds was open-ended and uncoerced; Lincoln argued that minds which could not see that slavery was an abomination were operating on the wrong principles.” Substitute critical topics of today in the place of slavery and the debates continue.[11]

[1] Abraham Lincoln, “Sixth Joint Debate, At Quincy, October 13, 1858,” in The Complete Papers and Writings of Abraham Lincoln: Constitutional Edition (Complete Seven Volumes), ed. Arthur Brooks Lapsley (Kindle edition) (Hereafter cited as Complete Papers).

[2] Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008), 34.

[3] Lincoln, “Speech At Springfield, June 17, 1858,” Complete Papers.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Harry V. Jaffa, Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, 50th Anniversary Edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 29-30.

[6] Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas, 268.

[7] Lincoln, “Speech At Springfield, July 17, 1858,” Complete Papers; Lincoln, “Speech At Chicago, July 10, 1858,” Complete Papers.

[8] Lincoln, “Speech At Springfield, June 17, 1858,” Complete Papers.

[9] Jaffa, Crisis of the House Divided, 9.

[10] Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas, xxi. (See also Michael J. Sandel, Democracy’s Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy, (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996).)

[11] Ibid.

1 Response to 1860 Politics – Lincoln-Douglas Debates Continue: Moral Consensus and Thin Democracy