Hints to Correspondents

This comes from the “The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same” file. The following newspaper submission guidelines appeared in the Portland, Maine, Daily Eastern Argus on May 10, 1864:

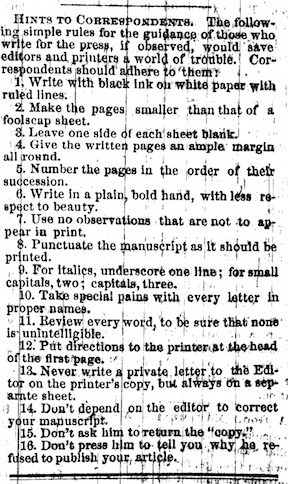

Hints to Correspondents: The following simple rule for the guidance of those who write for the press, if observed, would save editors and printers a world of trouble. Correspondents should adhere to them:

- Write with black ink on white paper with ruled lines.

- Make the pages smaller than that of a foolscap sheet.

- Leave one side of each sheet blank.

- Give the written pages an ample margin all round.

- Number the pages in the order of their succession.

- Write in a plain, bold hand, with less respect to beauty.

- Use no observations that are not to appear in print.

- Punctuate the manuscript as it should be printed.

- For italics, underscore one line; for small capitals, two; capitals, three.

- Take special pains with every letter in proper names.

- Review every word to be sure that none is unintelligible.

- Put directions to the printer at the head of the first page.

- Never write a private letter to the Editor on the printer’s copy, but always on a separate sheet.

- Don’t depend on the editor to correct your manuscript.

- Don’s ask him to return the “copy.”

- Don’t press him to tell you why he refused to publish your article.

A few things jump out at me as I read these helpful hints:

Every publication has its own submission guidelines, of course. We have ours. Few concern themselves with the author’s paper, pen, or handwriting anymore, but most do have specifications about how a manuscript should appear when an author submits it: font size, margins, line spacing, location of the page numbers.

Every publication has its own submission guidelines, of course. We have ours. Few concern themselves with the author’s paper, pen, or handwriting anymore, but most do have specifications about how a manuscript should appear when an author submits it: font size, margins, line spacing, location of the page numbers.

However, anyone who’s spent time reading handwritten letters, journals, and diaries from the Civil War can appreciate the value of Rule #6. Penmanship was once considered an artform, but damn if beautiful cursive isn’t a bear to read.

Rule #10 reminds me of a colleague in the journalism program where I teach: he fails students when they misspell a proper name on an assignment. If you think that’s tough, consider the legal and ethical ramifications of saying someone was accused of murder or rape—except they weren’t, although a misplaced letter or initial on your part misidentified them. Or, as a more embarrassing example, I once worked in an “Office of Public Relations and Marketing.” You never wanted to be the guy who left the “l” out of “Public.”

Rule #14 should come with a corollary: “Don’t depend on the editor to correct your manuscript—but don’t be surprised when he does, either.”

Rule #15: Text is called “copy” because it should be just that—a copy. Submit a copy to an editor and keep the original for yourself.

Rules #15 and 16 are revealing in a different way: “him.” While this is a specific set of rules for a specific newspaper that had a specific editor—J. M. Adams—the news business at the time was a male-dominated field. Today, some of the best reporters and editors in the business are women (and, in all honesty, the best newspaper editors I ever worked with were all women).

As an editor myself, I can attest that such lists of rules exist for one main reason: to make life as easy as possible for the editor. If that seems rather haughty, it’s not. On a typical day, aside from answering emails, doing various administrative stuff, and herding cats, I might have five or six pieces to edit for the blog and any number of book projects. In the midst of all that, do I want to deal with a submission that’s going to require a lot of work on my part or a submission that needs only minimal attention? Do I want to look at a piece that looks like a train wreck or one that’s crisp and clean? Do I want to waste time reformatting someone’s text or work with someone who’s formatted their text for me, thereby demonstrating that they follow directions?

Following submission guidelines becomes a practical matter, then, for a writer. In a competitive environment, what can you do to improve the chances that your manuscript will get considered? What can you do to save the editor “a world of trouble”?

The technology correspondents use today is vastly different than it was in 1864, but the intent remains the same: getting stories to readers. That brings to mind an observation a guest speaker made in one of my classes back in 2001. Jeff Wright was the editor of Business First in Buffalo, NY, and he told my students a hint I repeat to this day: “No new technology is ever going to replace good writing.”

Wish those guidelines could have made the rounds to all the letter writers

No kidding! Maybe the toughest part of our jobs, it seems, is deciphering handwriting! 😛

Several years ago when Twitter first became popular my son informed me (wise man that he is) that he would disown me if I acquired an account with them. As it turns out I had no such intention anyway so compliance came easy. Since then, I’ve become aware of the damage that is being done by this unbridled mess and Twitter’s reluctance – refusal really – to establish a set of guidelines by which its use will be permitted. Just yesterday I listened to a radio interview out of Seattle re: a woman who has been endeavoring to disarm Twitter “trolls” for the last five years and has finally decided she’s bored with the whole thing and is “signing off” for good. She’s endured all kinds of extraordinarily cruel insults and death threats for her efforts. I concede that this example may be a stretch given the content of your above posting, but on one level it may not be. The more we give opportunity to haters the further we seem to descend into a place we shouldn’t be. There’s a thin line between editing and censorship that shouldn’t be crossed, but too many folks don’t seem to know where common sense would place that line, and apparently don’t care.

I agree, social media has made it way to easy to be mean, and I think it’s made us an meaner society overall as a result.

As an editor, Mackowski is pretty good. When I began writing for ECW, I had no idea that there were differences between typing and keyboarding. Well, DUH! He very graciously informed me that, although when one types, one separates sentences with two spaces, when one is using a computer keyboard, one separates them with one. I kid you not–I blushed a deep red, even though there was no one else around and I was just in the “office” where I write. Nothing like being outed as a geezer! But–thanks, Chris!

Great, great list! Sharing this on my history Facebook page for Writer’s Wednesday.