Longfellow, the “Organ of Muskets,” and the Civil War

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

ECW’s December 24 re-posting of Meg Groeling thoughtful piece about Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1863 poem “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” was, for me, a welcome introduction to the work. No wonder it has become so popular within the ECW blogosphere around Christmastime.

The Christmas poem reflects key themes resonant in “The Arsenal at Springfield,” an earlier work Longfellow composed after visiting the Federal Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. (Scroll down for the full text.) Both poems share images of roaring cannons, testimonies to the chaos and destruction of war, and peace on earth restored with some help from the Almighty. “The Arsenal”— the longer and darker of the two poems— also projects the kind of despair and angst Meg points out Longfellow was experiencing during the Civil War and channeled into parts of “Bells on Christmas Day.”

Based on those clues, one might guess that the verses about the Armory visit had been inspired by the devastating war between North and South. In fact, it was written significantly earlier, in 1843. Yet the antebellum poem (scroll down to read it) is so appropriate to the bloody conflict that curators at the Springfield Armory National Historic Site (NHS) museum— located in the very arsenal building that Longfellow visited— have accorded it a key role in the interpretation of their permanent Civil War weapons collection.

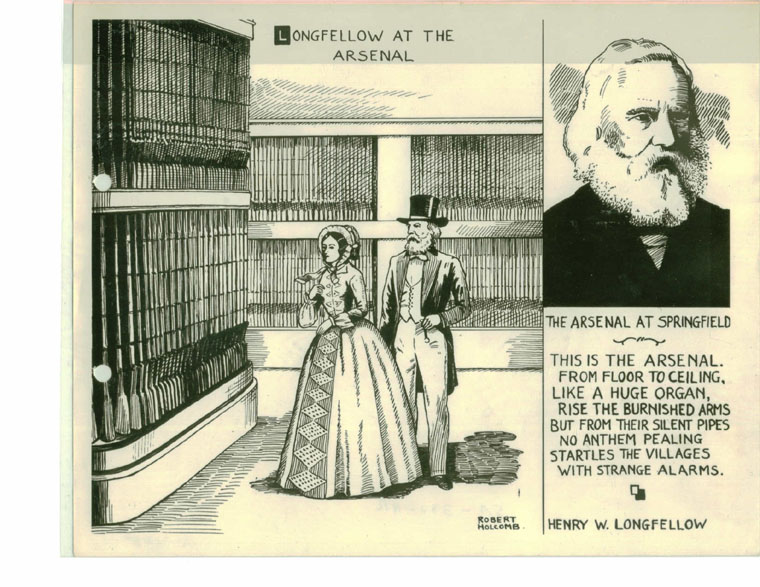

The poem’s twelve stanzas appear on the plaque introducing Armory Museum visitors to the centerpiece of the firearms exhibits, a two-tiered rack of the Springfield Model 1861 Rifle-Muskets manufactured here during the war. Although an earlier design than the 1861s, the muskets that Longfellow viewed looked much the same as the Civil War era rifles visitors to the museum see today. In my job as an education consultant at the National Historic Site, I have seen that the nearly ceiling-high stand— referred to in the poem as “an organ of muskets”— makes an indelible impression on most first time visitors.

For those unfamiliar with the Springfield Armory’s storied legacy, it was built by government decree in 1794, along with a sister Armory and Arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, that have their own significance in antebellum and Civil War history. Harpers Ferry arsenal was largely destroyed early in the conflict by Confederates retreating from advancing federal forces. The Springfield facility remained a leader in military weapons design and manufacture through the Nineteenth and on into the Twentieth Centuries. During the Civil War, its workers utilized the most advanced manufacturing technology and methods of the age to produce 800,000 of the Model 1861 Springfields. An estimated 700,000 of the weapons were produced at privately-owned facilities. The rifle-musket fired a .58 caliber Minie ball with deadly accuracy and was issued to most Union infantrymen.

The Longfellow poem about the Armory visit shares more than thematic commonplaces with “Bells on Christmas Eve.” That earlier work also was influenced significantly by the two people Meg identified in her blog posting as impacting the Christmas poem: Fanny, then his newly-wedded wife, and the poet’s friend and mentor, U.S. Senator-to-be Charles Sumner. In 1843 the Longfellows were on a honeymoon tour of Northeast landmarks and were joined by Sumner in Springfield. (While an operating federal arms manufacturing facility may seem an odd vacation or honeymoon destination by 21st Century standards, reportedly others paid leisurely visits to the Armory.)

All three of the Armory visitors opposed the “peculiar institution.” Henry Longfellow recently had published a volume of his works for the New England Anti-Slavery Association. Sumner would evolve into a fiery and outspoken abolitionist and become an anti-slavery icon when caned by a South Carolina congressman on the floor of the U.S. Congress in 1856. Yet standing in the Springfield Armory in 1843, surrounded by the most advanced weaponry of their age, issues of war and peace were forefront on their minds. Multiple weapons stands holding tens of thousands of firearms stood before them. Fanny later reported that she had commented to her companions that the stacked racks of rifle-muskets, each holding 1,100 rifles, resembled the pipes of a giant church organ. She wrote that “I urged H. to write a peace poem.” Longfellow did exactly that, seizing on Fanny’s simile for his poem, describing the racks of “burnished arms” standing “from floor to ceiling/ Like a huge organ.”

Where Longfellow’s “Bells” is specific to Christmastime and the Civil War, his poem about the Springfield Armory and the weapons made there is an examination of the dark face of modern armed conflict. The verse transforms the musket stand to an organ that plays the “anthem” of war. And “When the death-angel touches those swift keys/ What loud lament and dismal Miserere/ Will mingle with their awful symphonies.” Yet, as he will in the closing of his poem about Christmas bells, he envisions in “The Arsenal at Springfield” a divine intervention creating a world without war, where “holy melodies of love” will replace the discord of “War’s great organ.”

THE ARSENAL AT SPRINGFIELD

This is the Arsenal. From floor to ceiling,

Like a huge organ, rise the burnished arms;

But front their silent pipes no anthem pealing

Startles the villages with strange alarms.

Ah! what a sound will rise, how wild and dreary,

When the death-angel touches those swift keys

What loud lament and dismal Miserere

Will mingle with their awful symphonies.

I hear even now the infinite fierce chorus,

The cries of agony, the endless groan,

Which, through the ages that have gone before us,

In long reverberations reach our own.

On helm and harness rings the Saxon hammer,

Through Cimbric forest roars the Norseman’s song,

And loud, amid the universal clamor,

O’er distant deserts sounds the Tartar gong.

I hear the Florentine, who from his palace

Wheels out his battle-bell with dreadful din,

And Aztec priests upon their teocallis

Beat the wild war-drums made of serpent’s skin;

The tumult of each sacked and burning village;

The shout that every prayer for mercy drowns;

The soldiers’ revels in the midst of pillage;

The wail of famine in beleaguered towns;

The bursting shell, the gateway wrenched asunder,

The rattling musketry, the clashing blade;

And ever and anon, in tones of thunder,

The diapason of the cannonade.

Is it, O man, with such discordant noises,

With such accursed instruments as these,

Thou drownest Nature’s sweet and kindly voices,

And jarrest the celestial harmonies?

Were half the power, that fills the world with terror,

Were half the wealth, bestowed on camps and courts,

Given to redeem the human mind from error,

There were no need of arsenals or forts:

The warrior’s name would be a name abhorred!

And every nation, that should lift again

Its hand against a brother, on its forehead

Would wear forevermore the curse of Cain!

Down the dark future, through long generations,

The echoing sounds grow fainter and then cease;

And like a bell, with solemn, sweet vibrations,

I hear once more the voice of Christ say, “Peace!”

Peace! and no longer from its brazen portals

The blast of War’s great organ shakes the skies!

But beautiful as songs of the immortals,

The holy melodies of love arise.

Springfield Armory National Historic Site visitors can be awed by the elegant symmetry of the hundreds of “burnished arms” on display, with finely machined metal components and polished wood stocks. Focusing on the beauty in the exhibits and the cutting edge technology and craftsmanship evident in the individual firearms, it’s easy to overlook the deadly purpose of what’s on display. This is especially true for the high school and middle school students that I work with on Armory field trips, a generation whose understanding of war has been profoundly shaped by its glorification in popular internet games, movies, television shows and other forms of electronic media entertainment. As unfamiliar as some of the Victorian language and allusions within ”The Arsenal at Springfield” are to modern sensibilities, Longfellow’s poem juxtaposed with the Model 1861 Springfields in the “Organ of Muskets” can remind all of us—young and old— of the tremendous sacrifices, harsh realities and human costs of the Civil War and of all wars.

To access the “The Arsenal at Springfield” and for more information on Springfield Armory National Historic Site, go to http://www.nps.gov/spar/historyculture/organ-of-muskets.htm.

More information on Longfellow and the poem is available at https://www.nps.gov/spar/learn/historyculture/arsenal-at-springfield.htm)

What a lovely companion piece to my own! There may be another addition to this little series. I am reading much more about Longfellow, and his anti-slavery poems, although eating no fire, are yet another interesting aspect of this time period and the amazing folks who lived then. Thank you for your work, both at ECW and at Springfield. Huzzah!

And a hearty Huzzah back at ya! If anyone is in the mood for the next generation of Civil War poetry after Whitman, check out the “Drum Taps” poems in Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass.”

It has been of interest to me to see/hear Whitman’s verses, or bits of them, appear in a variety of television commercials.When Levis used the wax cylinder recording of “America” I about knocked the chair over running to see if I actually heard what I thought I was hearing. I found the following as well: http://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/walt-whitman/

I love Whitman–it was a series of articles on Whitman that brought me to Emerging Civil War in the first place.

That was a really interesting perspective on Whitman and the multitude of ways others have appropriated his legacy to their own ends. I never realized that… Thanks for sharing.

Love both of your articles about Longfellow! What a poet! Meg at the DuPont Circle Metro Station there is a beautiful excerpt of Walt Whitman’s work from his “The Wound Dresser”. It’s along the top of circular wall as you walk into the station:

“Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all the dark night—some are so young;

Some suffer so much—I recall the experience sweet and sad…” From his experiences as a nurse in DC hospitals during the war.

Love both of your articles! Meg at the DuPont Circle Metro Station there is an inscription of Walt Whitman’s. It’s at the top of the circular wall as you enter the station. It’s an excerpt from his “The Wounded Dresser”:

“Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all the dark night—some are so young;

Some suffer so much—I recall the experience sweet and sad…”

He wrote from his experience as a nurse at Washington DC hospitals during the war! Thought you’d enjoy!

Thanks Tim for sharing the Metro quote. I’ll look for it next time I’m in DC (DuPont Sq. is often a stop.)

This is not the only poem where Whitman assumes the persona of a participant in the Civil War looking back on his experience. If you don’t have a copy of Leaves of Grass, pick up a copy sometime in a bookstore… just a few pages after “The Wound Dresser” you’ll find “The Artilleryman’s Vision.” Like the Dresser poem, this work essentially is a flashback. This one is an intrusive vision of a past battle visiting a Civil War veteran in that twilight between sleep and awakening. “…this vision presses upon me; The engagement opens there and in fantasy unreal/ The skirmishers begin, they crawl quietly ahead, I hear the irregular snap! snap!…” And on it goes, the dark, chilling and involuntary recollection of a 19th Century firefight. It’s a dark and powerful examination of the horror of war, and how traumatic memories haunt many war survivors, both civilians (like the wound dresser) or combat veterans (like the Artilleryman).