Deliver Me From Anymore Southern Winters

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Rob Wilson

Army of the Potomac Private George Augustus Marden’s frequent letters home to family in Mont Vernon, New Hampshire, contained fascinating accounts of his Civil War experiences. Others carried disturbing news, such as his January 10, 1862, description of the grim scene unfolding repeatedly in front of his 2nd Regiment U.S. Sharp Shooters camp.

“There is a funeral or perhaps two every day and the Regimental Ambulance if there is one dead, and followed by a covered Sutter’s wagon if there are two, these preceded by the Buglers playing a Dirge… This procession has become so common that it excites hardly a remark more than ‘There goes another poor fellow in a box’, or ‘We all are going.’ ” [i]

The trauma of combat can make some soldiers indifferent and fatalistic about death, yet Private Marden and the 2nd Regiment had not engaged in any fighting. The soldier and his Company G comrades— all new recruits from New Hampshire— had been at their Washington D.C. Camp of Instruction only five weeks. It was nine months into the Civil War. Living in tents a mile and a half north of the partly constructed Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, the boys from the Granite State were marksmen without weapons: to their collective ire, the Army had yet to issue them the breech-loading Sharps rifles they were promised.

If not musket and artillery fire, what was keeping burial details busy and morale low? It was the silent winter killers of the Civil War: illnesses, contagions, infections and wet cold. Working in concert, they devastated both Union and Confederate ranks and were so grimly efficient at taking lives this winter in Washington, according to 2nd Regiment soldier Wyman White, that it became “out of the question to give all [who died]… a [formal] funeral.” Over the course of the conflict, various afflictions would take the lives of about 225,000 Union military personnel, more than the twice the number of the combat-related deaths of Union troops.[ii]

“Deliver me from anymore Southern winters,” pleaded Marden after seven weeks in Washington, complaining of the wind, sleet and mud “as deep as snow.” Making a comparison to colder Northern Januaries, he wrote: “Snow and ice are much more preferable.”[iii]

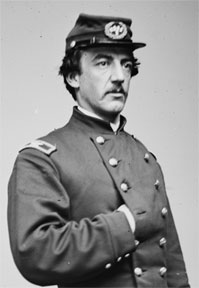

The 22-year old soldier— who is my great grandfather— mailed home 288 pages of correspondence from Washington before he was transferred to the Sharp Shooters 1st Regiment in late March for the Peninsula Campaign. His letters, including the one written January 10, are not entirely stories of winter cold, disease, suffering and death. They also are packed with amusing descriptions of Army routine, camp life, visits to the city, and encounters with a host of memorable people (including First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln). But for now— as the Middle Atlantic region battles this year’s harsh weather— I’m leaving those aspects of camp experience to be examined. What better time to turn the clock back 155 years and examine the realities of the cold, wet and windy winter of 1861-62 through George Marden’s experiences and observations?[iv]

The temperature regularly dipped and stayed below freezing when Marden wrote his December and January letters. He and his four A-frame tent mates had pooled their own money to purchase a small stove, some wall boards and planks for their floor costing “seven shillings apiece.” Even with the improvements, sleeping in the crowded and drafty canvas shelter— just seven feet by eight feet at the base— remained “a great puzzle.” The Sharpshooter and his comrades coughed, sneezed and shivered their way through the night, he wrote, keeping one another awake. At first he made light of the miserable weather, joking about Company G’s frigid morning routine and going for a wash to a nearby brook after 6:30 a.m. reveille. “There is usually a little frost on the edges, enough to make it comfortable, he wrote.”[v] The humorous tone changed in a letter written on Christmas Day.

“Our rain storm cleared off in a snow squall and came out in a gale of wind and a cold snap… I seldom have heard the wind blow harder, and it froze up tight… We could keep no fire for our stovepipe chimney blew down, and I have not passed such a disagreeable night on the ground… I can hardly help referring to this worst phase of winter camp vis treatment of the sick, and their number. Two hospital tents blew down leaving the sick unprotected… In our Reg. the 2nd, of 700 men 150 are on the sick list. Two men died night before last…”[vi]

In hindsight, we can see a wartime health crisis was inevitable. Tens of thousands of fresh recruits arrived in Washington from across the Northern states that first winter of the war, carrying with them a full variety of contagious diseases and illnesses. Many of the recruits— including Marden and his previously cited comrade, Wyman White— were from remote rural areas often isolated from diseases such as measles, mumps, and smallpox. Unlike soldiers raised in crowded cities, who had survived epidemics and developed immunities, these men took sick from contagions in droves, and many died. Deadly maladies such as typhoid, pneumonia and cholera also spread rapidly through the camps of the more than 100,000 troops camped in and around Washington.

“[Many of the sick] have measles which are followed by something else,” Marden reported in early January. “Today 17 of our company are reported to the sick list… Two of our men are very sick. One has measles and typhoid fever and is not expected to live till morning.”[vii]

Diarrhea and dysentery were the leading killers in both Union and Confederate ranks. The intestinal diseases were byproducts of the poor sanitary conditions and inadequate personal hygiene practices common throughout the ranks. Ill-kept toilet facilities dug into the ground easily overflowed— especially during wet wintry weather— to contaminate drinking water sources, while Federal Sanitation Commission literature on hygiene procedures often was ignored, especially early in the war. The Sharpshooters’ Washington camps drew the notice of no less than Dr. Charles Tripler, the Army of the Potomac’s Medical Director, who ordered the two U.S.S.S. regiments to improve their “bad sanitary condition.”[viii]

The foul, cold conditions continued well into the New Year. The sick over-flowed from hospital buildings into tents. The death rate skyrocketed. The miserable weather, harsh living conditions and delays in arming and training wore at the physical and emotional wellbeing of Marden’s entire regiment. A January 6 letter reveals his personal despair:

“I am somewhat blue tonight. I don’t hesitate to confess it. Here are men dying at the rate of two or three a day. Measles, mumps and scarlet fever have run the camp, and now diphtheria is making its appearance… I wish we might go [to war] tomorrow. As little as we are drilled and as unfit as we are for duty, I don’t believe more would be killed in a good smart action, than would die here in the same time.”[ix]

The relatively primitive state of medical training and practice in the early 1860s exacerbated the deteriorating health conditions. Formal medical education was just developing and both armies heavily relied on physicians who were ill-trained in two year programs (or worse). The causes and remedies for many killer diseases, sicknesses and infections were not understood. Medieval treatments such as bloodletting still were employed. Louis Pasteur was a few years away from establishing the relationship between germs and disease and revolutionizing medical science. Antiseptics had not been developed, and secondary infections after even minor surgery could prove fatal. When treating battle wounds, doctors commonly moved from patient to patient without washing. Looking back after the Civil War, Union Surgeon General William A. Hammond mused that the conflict “had been fought at the end of the Medical Dark Ages.”[x]

Marden personally experienced this “Dark Age” late that winter, when an abscessed molar was extracted by a camp doctor. He broke a chair during the excruciating procedure, which, he wrote, took a piece of his jawbone along with the tooth and left a hole large enough for “a small New Hampshire family to move into.” The soldier was bedridden for more than a week.[xi]

“I don’t think we shall ever be aware of the great changes this war will effect in us and our plans,” the Sharp Shooter wrote, reflecting on the future. “Many a poor fellow will leave a blank however which will serve to impress the war on those left behind. The monuments won’t be so many killed as died, and there will be crooked, rheumatic living monuments creeping home just often enough to show that the war is still at work.”[xii]

Marden’s somber vision became a reality in both North and South. The silent killers would take seven of the eight men from his tiny hometown who perished in the Civil War. North and South, they would kill 388,000 soldiers and disable tens of thousands more. This soldier, however, survived. He attained the rank of Lieutenant, served as an Assistant Adjunct General to his brigade and went on to successful post-war careers in the newspaper business and state politics in Massachusetts. Married, the father of two boys and the founder of the Lowell Grand Army of the Potomac post, the veteran was thankful and incredulous that he somehow dodged both Confederate bullets and fatal illnesses while serving in the Union cause.[xiii]

———-

[i] George A, Marden, from his unpublished Civil War Letters (Archived at Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College, Hanover NH; transcribed and edited by Robert Wilson), letter dated January 10, 1862

[ii] Time-Life Civil War Series, Federal Army Casualties, quoted on the American Studies Website, Masaryk University https://www.phil.muni.cz/~vndrzl/amstudies/civilwar_stats.htm; http://www.historynet.com/civil-war-casualties; http://www.civilwar.org/education/civil-war-casualties.html; Wyman S. White (Ed. Russell C. White) The Civil War Diary of Wyman S. White: First Sergeant, Company F, 2nd United States Sharpshooters (Baltimore: Butternut and Blue, 1993), 23

[iii] Marden letters, Jan. 26, 1861; Feb. 1, 1862

[iv] Marden letters, Dec. 22, 1861; Jan. 7, 1862

[v] Marden letters, Dec. 22

[vi] Marden letters, Dec. 25

[vii] Drew G. Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and Dying in the Civil War (New York; Vintage Books, 2008) 62-63; Michael C.C. Adams, Living Hell: The Dark Side of the Civil War (Baltimore; John Hopkins Press, 2014) 23, 25; Denney, 8-9; Terry L. Jones, Opinionator, New York Times, http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/26/brother-against-microbe/?_r=0, first published Oct. 26, 2012; Marden letters, Jan. 2

[viii] “Medical Care, Battle Wounds, and Disease,” Shotgun’s Home of the Civil War, last modified 2/10/02

http://www.civilwarhome.com/civilwarmedicine.html [Note: Confederate forces, who had shortages of provisions and suffered greatly from insufficient nutrition, especially in the war’s latter years, experienced higher rates of intestinal maladies and were more likely to be susceptible to death by disease than Union soldiers.]; Robert E. Denney Civil War Medicine: Care and Comfort of the Wounded (New York, Sterling Publishing, NY, 1995 (paperback edition) 62-3; Dr. Charles S. Tripler, January 28, 1861 report, quoted in Roy M. Marcot, U.S. SharpShooters: Berdan’s Civil War Elite (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books 2007) 30

[ix] Marden, letters, Jan. 6

[x] Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Civil War (Baton Rouge; Louisiana State Univ. Press, 2008) 124-5; “Medical Care, Battle Wounds, and Disease,” Shotgun’s Home of the Civil War, last modified 2/10/02 http://www.civilwarhome.com/civilwarmedicine.html; Denney, Civil War Medicine 7, 8; Jones, “Brother Against Microbe”, Opinionator, New York Times, [Perhaps the most famous Civil War example of death from complications after surgery is Stonewall Jackson, who developed pneumonia after his badly wounded arm was amputated and subsequently died.]

[xi] Marden, letters, Mar. 2

[xii] Marden letters, Feb. 1

[xiii] “A Brief, Early H I S T O R Y of Mont Vernon, NH” http://www.nh.searchroots.com/HillsboroughCo/Montvernon/history.html; Civil War Preservation Trust, www.civilwar.org/education/pdfs/civil-war-curriculum-stats.pdf

Interesting article !

Thanks David.

leaving near Buffalo can relate chill you to the bone .what truly heroes were all these men Thank you Rob for the tribute and memory of your great grandfather

You are welcome Thomas and thanks for your comment.

LIVING NOT LEAVING DUH